Durham Food History

The colonization of what is now called the Americas was a specific type called “settler colonialism.” In this form, colonists seek to replace the original population of the territory with a new society of settlers. English colonists first came to what is now North Carolina to start the failed Roanoke colony in in 1585, but permanent settlement did not begin until the late 1600s. By teaching colonists how to forage, clear land, what seeds to plant, and how to select and care for crops, Native Peoples contributed to colonists’ early survival. However, the culture of welcome clashed sharply with the culture of conquest, theft, and subjugation, and the sovereignty and autonomy of Native Peoples, and the land on which they lived, was immediately threatened. Over the next 300 hundred years, European settler-colonialists used systemic violence, terror, false promises, and a foreign legal system to claim Native homeland.14-16

"[The Indians] are really better to us than we are to them; they always give us victuals at their quarters, and take care we are armed against hunger and thirst. We do not do so by them (generally speaking), but let them walk by our doors hungry, and do not often relieve them. We look upon them with scorn and disdain, and think them little better than beasts in humane shape. Though if well examined, we shall find that, for all our religion and education, we possess more moral deformities and evils than these savages do not."

- John Lawson, English settler-colonist in North Carolina, 170917

Much of the non-European world was colonized under the guise of the Doctrine of Discovery - a unilateral decree of international law issued by Pope Alexander VI in 1493 that categorized Indigenous Peoples as subhuman because they were not Christian and treated their land as unoccupied and available for the taking. In the early colonial period, there were sometimes treaties entered into or token payments made for use or purchase of Native People’s land. But predominantly, outright theft, enforced by violence, was the method of colonial land control. In 1663, by a decree from King Charles II, the colonial British Empire seized all the land of Native Peoples between 31 and 36 degrees latitude (an area extending from the today’s southern Georgia border to North Carolina’s northern border), from the east to the west coasts. Eighty years later, King George II of England awarded the Earl of Granville the upper half of what is now North Carolina. This area, which contained what is now Durham County, included 26,000 square miles stretching from the Atlantic Ocean to an indefinite western boundary. In the Carolina colony, Granville’s agents carved up stolen Native People’s land into parcels which were sold to English settlers. Ownership of these parcels was bestowed through land grants. With this legal document, the land and all its resources became private property, from the minerals below the soil to the birds in the sky above. Private land ownership as we know it had not previously existed in the Americas; but it became the cornerstone of the law, and the necessary prerequisite for generational wealth, privilege, and power.3

In the early 1700s, an excursion of English passed through the land near what is now Durham, North Carolina and remarked that “They had never seen 20 miles of such extraordinary rich Land, laying all together, like that betwixt the Haw River and the Occoneechee Town.” The gently rolling land had plentiful streams and rivers and old-growth forests with hardwood trees along the waterways and conifers on the ridges. Far more varieties and numbers of wildlife and plants lived in the forests than are found today. One of the most important north-south trading routes of Indigenous Nations ran right through what is now Durham County (approximately the route of I-85), and many communities of Native Peoples located in convenient proximity to it. The sparse surviving accounts indicate that until the 1740s, the Native Peoples of this area traded with European settlers from the north and east and occasionally hosted small groups of travelers. But by the time permanent European settlers encroached upon the area in the 1750s, most of the Native Peoples of this area had left to join other tribes in the north and west with whom they had alliances. However, some members of the Occaneechi stayed and established a farming community near what is now called Hillsborough, though their food systems were profoundly disrupted by the privatization of tribal hunting and fishing grounds. One contemporary member of the Occaneechi described their existence over the next 200 years as “hiding in plain sight.” This phrase acknowledges that despite maintaining Indigenous identity and cultural practices, the continued presence of Native Peoples was not acknowledged in census records and other official historical accounts. This process has been described as “administrative geocide.” Native Peoples also experienced attempted erasure through removal from the land and forced assimilation in boarding schools, where they were forced to speak English, practice Christianity, and wear European clothes.4

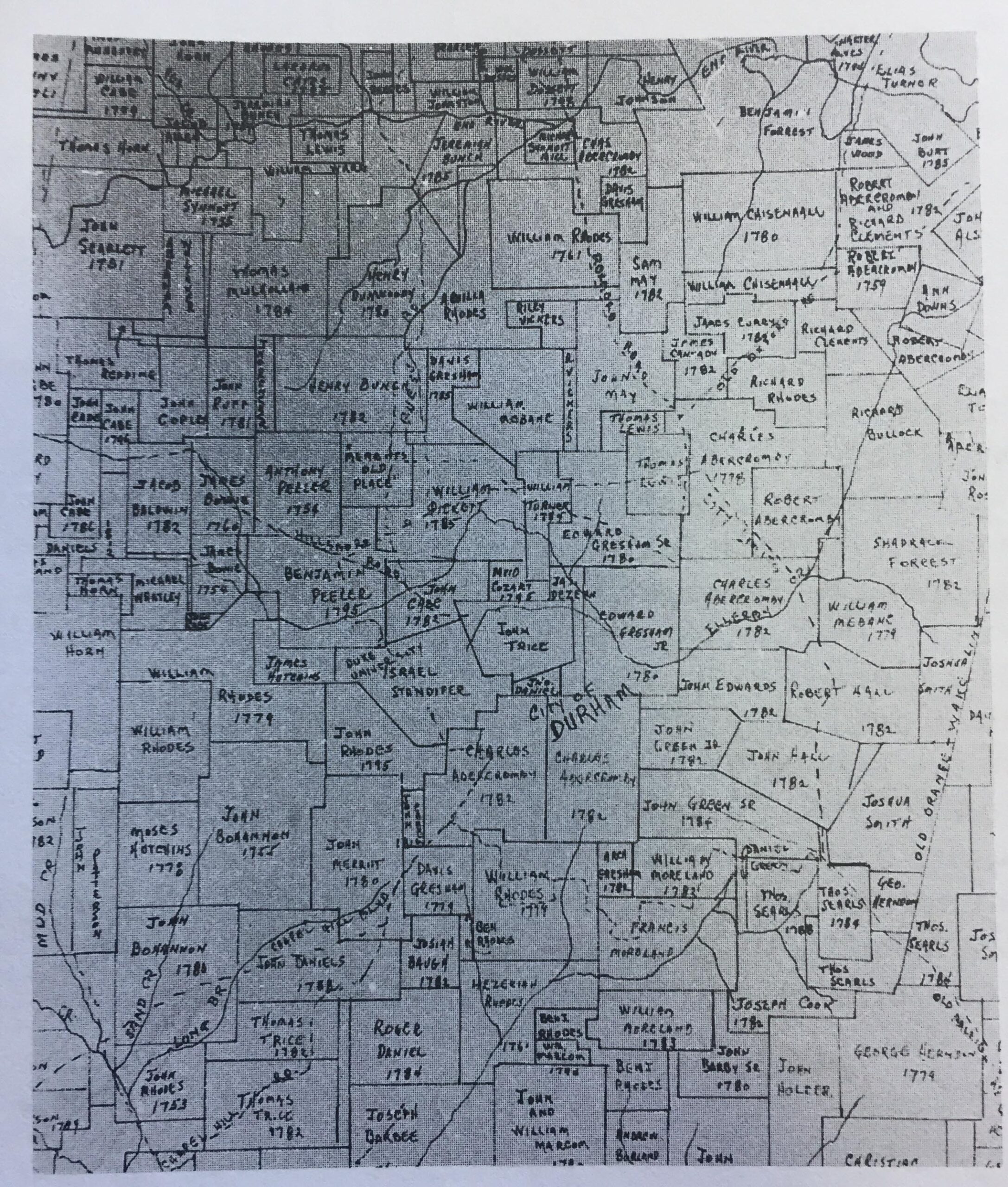

Map showing the names and property boundaries of land grant recipients in a section of what is now Durham County.

My name is Alex Woods. I was born May 15, 1858. In slavery time, I belonged to Jim Woods of Orange County. The plantation was between Durham and Hillsboro near the edge of Granville County. My missus name was Polly Woods. They treated us tolerable fair. Our food was well cooked. We were fed from the kitchen of the great house. We called master’s house the ‘great house’ in them times. We called the porch the piazza. We were fed from the kitchen of his house during the week. We cooked and ate at our homes Saturday nights and Sundays. We wove our clothes; children had only one piece, a long shirt. We went barefooted, and in our shirt tails, we youngins’ did… They allowed my father to hunt with a gun. He was a good hunter and brought a lot of game to the plantation. They cooked it at the great house and divided it up. My father killed deer and turkey. All had plenty of rabbits, possums, coons, and squirrels… Missus chewed our food for us, when we was small. The babies was fed with sugar tits, and the food missus chewed. Their suckled mothers suckled them at dinner, and then stayed in the field till night. I remember missus chewin’ for me, an the first whipping I got..”

– Alex Woods, formerly enslaved person from Orange County39

My mammy belonged to Tom Edward Gaskin and she wasn’t half fed. The cook nursed the babies while she cooked, so that the mammies could work in the fields, and all the mammies done was stick the babies in the kitchen on their way to the fields. I heard mammy say that they went to work without breakfast, and that when she put her baby in the kitchen she’d go by the slop bucket and drink the slops from a long-handled gourd.

- Martha Allen, formerly enslaved person from Craven County, who later lived in Raleigh10

The settlers in the area that is now Durham hailed primarily from England, Scotland, and Germany. Upon arrival, they cleared land and started farming in the rich, but unfamiliar, terrain. Soil was the primary asset of this land, and the settlers mined the natural fertility of the soil without a skillset or cultural framework of sustainable stewardship. The majority of settlers were small-scale, or yeoman, farmers who grew food and commodities for subsistence, barter, and limited market opportunities. The primary reason for the lack of market opportunities was that there were few roads by which to transport surplus crops. The crops grown included corn, wheat, cotton, an assortment of fruits and vegetables, and tobacco. Farms were diversified enterprises where livestock played an integral role. Sheep were raised for their wool and meat; cattle for their milk, leather, and meat; mules and horses for pulling plows and wagons; hogs for pork, ham, bacon, lard, and leather; and all the animals for the valuable manure they supplied.31-32

In the early phase of settlement, the land was rich and productive, but due to the dense and rocky soils of the Triassic Basin, the majority of Durham lands lacked natural fertility after the original deep layer of topsoil eroded. By the mid-1800s, the constant reuse of the soils without rest, replenishment, fertilization, crop rotation, or erosion prevention resulted in diminished yields. When no new land was left to clear, the average farmer’s income began to decline and it was more difficult to live off the land.33-35

The transformation and cultivation of the land in North Carolina could not have taken place without the farm labor of enslaved West African people, who were taken by force from their homeland from the 1500s through the 1800s. Working from dawn to dusk, enslaved people provided the free farm labor on stolen land that was the basis of the economy and the foundation of the wealth of this nation. When the Civil War began in 1861, nearly one out of three people in what is now Durham County were enslaved, and about a quarter of white farmers legally owned enslaved people. The Cameron Plantation, located largely in Durham County, was the largest in the state.36

Context played an important role in the enslaved person’s food, including size of farm, quality of land, and values of the enslaver. On the Cameron Plantation, food for enslaved people was distributed as a weekly allotment- usually on a Saturday after work ended- and likely included meat (pork), corn meal, a sweetener such as molasses, potatoes and other vegetables when in season. Allotments were augmented through fishing and hunting game like deer, squirrels, possums, and rabbits. The fruit available was mostly apples, pears, wild berries, and different varieties of grapes.37-38

As enslaved people endured the profound injustices of slavery, food became a connection to home and land, and a focal point of community. The seeds of West African foods, like yams, arrowroot, bananas, various types of beans, cowpeas, guinea squash, hibiscus, millet, okra, pigeon peas, plantains, purslane, rice, sesame, sorghum, sweet potatoes, tamarind, taro, and watermelon traveled to this land along with enslaved West African people. Stories have been passed down about how women braided treasured seeds into their hair before being forced onto transatlantic slave ships. Many of these African foods became a permanent part of food culture in the South. There were other through lines of West African food culture. In the fields, the West African food tradition of serving a grain covered with a vegetable stew was adopted. This thick gruel could be easily eaten with the fingers, which was necessary as utensils were seldom made available. A measure of food autonomy for enslaved people took the form of gardens, where various types of greens, beans, fruits and other vegetables were raised for personal and communal use. However, it was common practice for overseers to limit enslaved people’s ability to sell extra food or even trade beyond the immediate community.41-42

An intimate relationship with the land and contact with Native Peoples yielded knowledge held by enslaved people about wild herbs and edible foods to forage. Many of these plants had medicinal qualities. For example, the use of sassafras tea as a health tonic, sugared horehound as a lozenge for bad colds, and asafetida root or nettle for teething babies are commonly recounted. Native Peoples also influenced Black food preparation, especially various ways to prepare corn and meat. This includes the culinary art of barbecue, which is often attributed to the intermeshing of food traditions of Native and African Peoples. Although it is left out of dominant historical narratives, there was both physical contact and cultural exchange between Indigenous Peoples and enslaved African peoples over time. In the early period of colonization, African and Native Peoples were jointly enslaved, whereby they intermarried and lived through the same struggles. Later on, it was not uncommon for Native communities to take in Black people running away to escape enslavement. In certain parts of the state, free Black people lived in close proximity to Native communities by which further exchange could occur.43-48

The tradition of the communal Sunday dinner after worship services develops among enslaved people and was interwoven with deep religious, social, and cultural meaning. As described by a contemporary observer in Adrian Miller‘s history of soul food, “It [Sunday dinner] has to do with communion. Communion was a meal, a feast of love. It is a kind of extension of our Africanness."49

“We worked in the day and had the nights to play games and have singings. We never cooked on a Sunday. Everything we ate on that day was cooked on Saturday. They wasn’t lighted in the cook stoves or fire places in the big house or cabins neither. Everybody rested on Sunday. The tables was set and the food put on to eat, but nobody cut any wood and they wasn’t no other work on that day.”

- Tempe Herndon, formerly enslaved woman from Chatham County who made her home in Durham50

After the Civil War ended in 1865, Union soldiers rode across the South notifying enslaved people that they were now free. On the Cameron lands, the first act of freedom for many was to feast. Livestock were killed and eaten, smokehouses emptied, and storehouse wares cooked up in exuberant jubilee.51-52

References

- Settlement of North Carolina. NCPEDIA. Retrieved from https://www.ncpedia.org/history/colonial/early-settlement;

- Emory, Frank, et al. eds., (1976). Paths Toward Freedom: A Biographical History of Blacks and Indians in North Carolina by Blacks and Indians. Raleigh: The Center for Urban Affairs, North Carolina State University. p.16-17

- Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne. (2014). An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States. Boston: Beacon Press, p.9-10

- Lawson, John. (1984). A New Voyage to Carolina. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, p. 243

- Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne. (2014). An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States. Boston: Beacon Press, p. 198-199

- Some of the treaties between European settlers and Native Peoples of North Carolina listed in “North Carolina American Indian History Timeline,” North Carolina Museum of History. https://www.ncmuseumofhistory.org/american-indian/handouts/timeline

- Lords Proprietors. NCPEDIA. Retrieved from https://www.ncpedia.org/lords-proprietors

- Granville Grant and District. NCPEDIA. Retrieved from https://www.ncpedia.org/granville-grant-and-district

- Land Grants. NCPEDIA. Retrieved from https://www.ncpedia.org/land-grants-part-3-land-grants-and district

- Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. (1901). North Carolina Land Grants and Deeds, 1711-1861; 1901. Collection no. 00553 Southern Historical Collection. Retrieved from http://www.lib.unc.edu/mss/inv/n/North_Carolina_Land_Grants_and_Deeds.html

- Lawson, John. (1984). A New Voyage to Carolina. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, p. 61

- Anderson, Jean. (2011). Durham County. Durham: Duke University Press, p. 3-4

- Hazel, Forest. (1991). Occaneechi-Saponi Descendants in the North Carolina Piedmont: The Texas Community. Southern Indian Studies, 40, p. 3-30

- Oakley, C.A. (2005). Keeping the circle: American Indian identity in eastern North Carolina 1885-2004. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 14-15

- Description of “hiding in plain sight” provided by Vivette Jefferies Logan of the Occaneechi Band of the Saponi Nation to Melissa Norton in 2019

- Starna, William. (1992). Public Ethnohistory and Native-American Communities: history or administrative genocide? Radical History Review, 53, p.137

- Deerinwater, Jen. (2019). Paper Genocide: The Erasure of Native Peoples in Census Counts. Rewire.News. Retrieved from https://rewire.news/article/2019/12/09/paper-genocide-the-erasure-of-nat...

- Anderson, Jean. (2011). Durham County. Durham: Duke University Press, p. 20

- Anderson, Jean. (1985). Piedmont Plantation: the Bennehan-Cameron Family Lands in North Carolina. Durham: Historical Preservation Society of Durham, p. 69, 72

- Kirby, Robert M. (1976). Soil Survey of Durham County, North Carolina. Washington, D.C., p. 6-34

- Cathey, Cornelius. (1056). Agricultural Developments in North Carolina 1783-1860. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, p. 45-46

- Anderson, Jean. (1985). Piedmont Plantation: the Bennehan-Cameron Family Lands in North Carolina. Durham: Historical Preservation Society of Durham, p. 65

- United States Census Bureau. Distribution of Slaves in 1860. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/history/www/reference/maps/distribution_of_slaves...?

- Miller, Adrian. (2013). Soul Food: The surprising story of an American cuisine, one plate at a time. Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, p. 19-20

- Anderson, Jean. (1985). Piedmont Plantation: the Bennehan-Cameron Family Lands in North Carolina. Durham: Historical Preservation Society of Durham, p. 75

- Library of Congress. Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project, Alex Woods, 1936. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/collections/slave-narratives-from-the-federal-writer...

- Library of Congress. Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project, Martha Allen, 1936. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/collections/slave-narratives-from-the-federal-writer...

- Miller, Adrian, (2013). Soul Food, Soul Food: The surprising story of an American cuisine, one plate at a time. Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, p. 17-18, 24-25

- White, Monica. (2018). Freedom Farmers: Agricultural Resistance and the Black Freedom Movement. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, p. 11-13

- Hudson, Charles. (1976). The Southeastern Indians. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, p. 498–99

- Jones, Alice Eley. (1986). Afro-American Cultural Traditions at Stagville and Fairntosh Plantations. Stagville State Historic Site.

- Twitty, Michael. (2005). Barbecue is an American tradition-of enslaved Africans and Native Americans. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/jul/04/barbecue-american-...

- Snyder, Christina. (2010). Slavery in Indian Country: the changing face of captivity in early America. Boston, Harvard University Press, p. 46–79

- Yarbrough, Fay A. (2008). Race and the Cherokee Nation: sovereignty in the nineteenth century. Cherokee Nation. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008, p. 112–123

- Murray, Pauli, (1956). Proud Shoes: the story of an American family. Boston: Beacon Press (1999 ed.), 38.

- Miller, Adrian. (2013). Soul Food, Soul Food: The surprising story of an American cuisine, one plate at a time. Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 2013, p. 27, 55, 60 (quote)

- Library of Congress. Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project, Tempie Herndon, 1936. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/collections/slave-narratives-from-the-federal-writer...

- Anderson, Jean. (1985). Piedmont Plantation: the Bennehan-Cameron Family Lands in North Carolina. Durham: Historical Preservation Society of Durham, p.117

- Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, (1865) Thomas Ruffin Papers #641, Southern Historical Collection, Paul Cameron to Thomas Ruffin