Durham Food History

In the 21st century, a new set of dynamics in the increasingly urbanized Durham landscape present new challenges for food justice. What is often described as ‘gentrification’ is the latest in the legacy of involuntary displacement of people of color in Durham dating back to the Eno and Occoneechi. Indeed, the colonial worldview and the “frontier” mythology pervade how gentrification is talked about in many spaces. Words and phrases such as “urban pioneers” and “trailblazers” to describe the predominantly white and wealthier newcomers in historically disinvested areas described as “burgeoning,” “up and coming,” or even the “wild wild west.” This language pervades the popular press, real estate advertisements, and colloquial conversations, particularly among those with race and class privilege.314-315

The foundation of gentrification today was built through decades of chronic racialized disinvestment in the central city. These practices ultimately devalued real estate to such an extent that it became profitable for investors to come in and start making money. In the early 90s, the public sector laid the groundwork for a more favorable investment climate through a string of incentives for development projects downtown. This included the Durham Bulls Athletic Park (1995), the renovations of American Tobacco (Phase I, 2005) and West Village, Durham Central Park and the Farmers Market Pavilion (2007), the Durham Performing Arts Center (2008), and extensive streetscape and infrastructure improvements. The quickly expanding cluster of jobs and amenities resulted in a new premium for real estate in proximity to downtown. During this time, the downtown economy was undergoing dramatic changes. Instead of being comprised of factory workers, government employees, and non-profit workers, the new economy workforce is largely split between low-pay service jobs and high-paying ones in sectors such as research and technology. Unlike a generation earlier, where the middle-class fled the central city for the suburbs, high-wage earners today favor the walkability, amenities, historic character, and “diversity” of urban living and working environments.316-317

Further contributing to gentrification is the rapid population growth of the Triangle region which is expected to add over a million people from 2010 - 2040. This growth is putting a strain on the housing supply and attracting an influx of investment capital. Locally, this investment shows up as house flipping, a proliferation of Air B&Bs, and signs on central city neighborhood corners offering to ‘buy ugly houses.’ In the bigger picture, global hedge funds and investment companies have found they can get a better return on their investment in local real estate than in the stock market, and there has been a sharp increase in the amount of out of town ownership in Durham. While neighborhoods often see positive changes like reduction in crime, new public and private amenities, and fixed up houses and commercial buildings, the benefits do not accrue equitably across race and class. Rather than a tide that lifts all boats, gentrification is a process with winners and losers. Those that cannot afford the expensive new housing prices in Durham are displaced through rent increases, evictions, and foreclosures. During the Great Recession foreclosures spiked and were disproportionately located in historically Black neighborhoods, which were targeted for high-cost subprime loans by lenders in a practice known as “reverse Redlining.” Durham County had more than 10,000 eviction filings in 2016 and 2017, the highest rate of any large county in the state, and the average rent in Durham increased more than 35% between 2011and 2017. To put this into perspective, Durham was number 12 in the entire country for cities where housing prices are increasing the most.318-323

Over the past 40 years, many social services involved with emergency food and shelter programs located in central Durham to be accessible to high-poverty neighborhoods located nearby. These include organizations such Urban Ministries, Durham County Social Services and Public Health Departments, the Durham Housing Authority offices, and amenities such as the downtown library and the transportation hub. As these neighborhoods gentrify and long-time residents get displaced, there is an increasing spatial disconnect between the location of the services and amenities and those who utilize and need them the most.es-are-rising-the-fastest-slowest/.

Food, housing, and retail gentrification are closely intertwined. This is especially true in a place like Durham that has developed a national reputation for a “foodie” culture lauded in publications such as the New York Times, Bon Appetite, and Southern Living. Microbreweries, fair trade coffee shops, artisanal food trucks, and other hallmarks of foodie culture often serve as gentrification’s leading edge by signifying that a community is ripe for investment. Gentrification also changes what food retailers exist in the local food environment, sometimes creating “food mirages,” where high quality food is priced out of reach of longtime residents. There is also the issue of who is able to participate in the flurry of food entrepreneurism. Persistent racial discrimination in lending, less access to family wealth and well-resourced peer networks for seed money, and the high price of real estate are all barriers to entry for food entrepreneurs of color. Out of the 90 food businesses downtown, less than a fifth are owned by people of color, less than 10% by Black proprietors, despite the fact that Durham is a ‘minority-majority’ city.326-329

Closely linked with foodie culture is the ethos of individual consumer choice as food activism, expressed in such sentiments as ‘voting with your fork’ or ‘eating for change.’ From this perspective, food choices serve as a mirror of personal values, and so a person may choose to buy foods branded as organic, natural, grass-fed, local, fair trade, etc. as an expression of their health consciousness or personal politics. In Durham today, these types of food are readily available, albeit for premium prices, but there are contradictions in this philosophy. Even if these foods are healthier and more sustainable, their higher cost makes them unattainable to many people. Moreover, while all sorts of green branding attracts high-paying customers, differences in the treatment of workers, animal conditions, and ecological impacts are often negligible- or at the very least are unverifiable to the customer. With the growing popularity of organic food, there has been considerable corporate consolidation and control of organic products. For example, in 1995 there were 81 independent organic processing companies in the United States. A decade later, all but 15 had merged with large corporate food operations. The privilege of ‘voting with your fork’ will not make broader systemic changes in the industrial food system without more explicit connections to the social movements that address the root causes of the food inequities, such as land justice, worker justice, and immigration justice.330-332

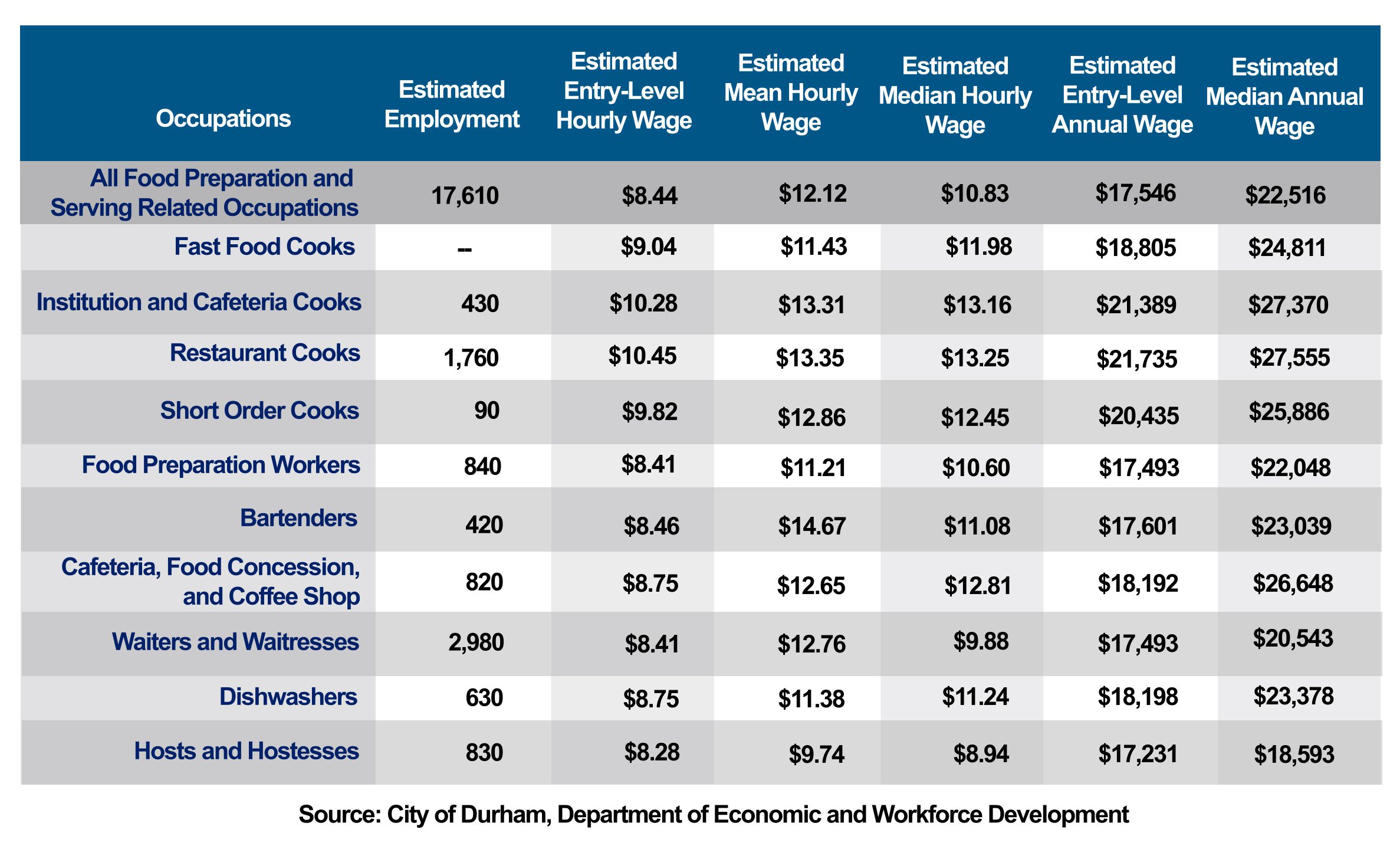

In the United States today, seven out of the ten lowest paying jobs are for the work involved in planting, harvesting, processing, packing, transporting, preparing, serving, and selling our food. In Durham County in 2019, the average hourly wage for food preparation and serving related occupations was $10.83 an hour, or $22,516 annually before taxes. Given that the fair market rent for a two bedroom housing unit in Durham County in 2018 was $900, these wages are all but impossible to live on without government assistance. However, it is individuals, not corporations, who bear the stigma, logistical burden, and hardship of economic insecurity. In Durham, whereas many central city neighborhoods saw the average price per square foot for residential sales go up more than 400% in the past decade, the minimum wage has not changed in that time. With wage stagnation and rapid housing price escalation, households are paying more for housing now than at any time in Durham’s history. In addition to the threat of displacement, this means that there are fewer resources for other necessities like food and healthcare, which increases food insecurity. With few other options, low-wage workers in Durham are organizing for economic justice. Our Walmart and the Fight for 15 are among the new worker movements fighting for higher wages, reliable scheduling, and workers’ rights. As Rita B. from Durham’s Fight for 15 puts it: “For me, $15 an hour means better living, access to healthcare, and money to feed myself and my family.”333-336

In the midst of historic levels of inequality and an impending ecological crisis, new models of resistance, resilience, and innovation are needed more than ever. Kamal Bell founded Sankofa Farms just outside of Durham in Efland, North Carolina, in 2016. Inspired to shift the focus of his life after reading Elijah Muhammad’s Message to the Black Man in America, Bell created Sankofa as an educational farm that aims to reclaim Black agricultural heritage by connecting youth to the power, healing, and knowledge made possible through a connection to land and the source of our food. Sankofa’s Agricultural Academy works with Black youth from the ages of 11-17 using agriculture for STEM education, earn money, build career readiness skills, and improve school performance. Others in Durham are focusing on food at the intersections of just sourcing, living wages, and cultural heritage. For example, PIRI is a Black woman-owned and operated business based out of East Durham that makes food deeply connected to their identity and roots- utilizing Southern family recipes that have been passed down for generations in the South as well as flavors and recipes inspired by the African diaspora. PIRI enacts equitable business practices using local and organic food whenever possible, sourcing sustainable products, and paying all their employees a living wage.

In a remarkable feat of resilience, the Occoneechi Band of the Saponi Nation was awarded official recognition by the state of North Carolina in 2002, following 20 years of organizing and sustained advocacy. Their first act was to acquire a 250-acre plot of land just outside of what is today called Durham County, and to plant an orchard of fruit-bearing trees for collective tribal use. It was the first land the tribe has collectively owned in more than 250 years.

References

- Farmerworker Justice. (2011, updated 2017). Farmerworker Justice Special Immigration Policy. Retrieved from https://www.farmworkerjustice.org/sites/default/files/documents/7.2.a.6%...

- Nuevo Espíritu de Durham: New Spirit of Durham. 13 Sept. 2019 -5 Jan. 2020, the Museum of Durham History, Durham.

- Smith, Neil. (1996). The New Urban Frontier: gentrification and the revanchist city. London: Routledge Press, p. 12-18

- Durham Magazine. (2018). The Downtown Pioneers. Retrieved from https://durhammag.com/the-downtown-pioneers/

- Downtown Durham, Inc. (2017) Downtown Master Plan: a Framework for the Future. Retrieved from https://downtowndurham.com/cms/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Final-Durham-M...

- Florida, Richard. (2002). The Rise of the Creative Class: and how it’s transforming work, leisure, community, and everyday life. New York: Basic Books, p. 231-241

- Triangle J Council of Governments. (2020). North Carolina Office of State Budget and Management (OSBM) Certified 2018 County Population/Municipal Population Estimates. Retrieved from https://www.tjcog.org/data-resources-regional-data-center/data-statistics

- Dataworks NC project. (2019). Who Owns Durham? Retrieved from https://dataworks-nc.org/2019/who-owns-durham-recap/

- Durham Human Relations Commission. (2018). 2018 Report on Eviction Crisis in Durham County. Retrieved from https://durhamnc.gov/DocumentCenter/View/20496/Durham-Eviction-Report-an...

- Husan, Asma. (2016). Reverse Redlining and the Destruction of Minority Wealth. Michigan Journal of Race and Law, 22. Retrieved from https://mjrl.org/2016/11/02/reverse-redlining-and-the-destruction-of-min...

- Rent Jungle. (2020). Rent Trend Data in Durham, North Carolina. Retrieved from https://www.rentjungle.com/average-rent-in-durham-rent-trends/

- Priceonomics Data Studio. (2019). Where Home Prices are Rising the Fastest (Slowest) in America. Retrieved from https://priceonomics.com/where-home-prices-are-rising-the-fastest-slowest/

- Nuevo Espíritu de Durham: New Spirit of Durham. 13 Sept. 2019 -5 Jan. 2020, the Museum of Durham History, Durham.

- Brother Ray Eurqhart. (2016). Personal communication with Rachel Barber for Video for Social Change class, Duke University.

- Moskin, Julia. (2010). Durham, a Tobacco Town, Turns to Local Food. New York Times (New York), Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2010/04/21/dining/21carolina.html

- Wartzman, Emma. (2017). The Ultimate Walking Weekend in Durham, NC. Bon Appetite. Retrieved from https://www.bonappetit.com/story/durham-nc-restaurants-guide

- Cohn, Nevin. (2018). Feeding or Starving Gentrification: the role of food policy. CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute Policy Brief. Retrieved from https://www.cunyurbanfoodpolicy.org/news/2018/3/27/feeding-or-starving-g...

- Analysis of ownership, by race, of downtown Durham restaurants done by Melissa Norton, November 2019

- Pollan, Michael. (2006). Voting with Your Fork. New York Times (New York). Retrieved from https://michaelpollan.com/articles-archive/voting-with-your-fork/

- Conrad, Allison. (2020). Evaluating White Dominant Narratives and White Supremacy in Food Policy and Programming. Masters Thesis, Sanford School of Public Policy, Duke University, p. 16

- Howard, Phil. (2017). Organic Processing Industry Structure. Retrieved at https://philhoward.net/2017/05/08/organic-industry/

- Wage data provided by the City of Durham, Office of Economic and Workforce Development

- McMillan, Tracey. (2012). The American Way of Eating: undercover at Walmart, Applebee’s, farm fields, and the dinner table. New York: Scribner

- Durham Bull City 150 exhibit. (2017). Uneven Ground: the foundations of housing inequality in Durham, NC

- McDonald, Thomasi. (2019). Durham Service Workers Share Stories of Poverty Wages and Poor Working Conditions. Indy Week. Retrieved from https://indyweek.com/news/durham/durham-service-workers-fight-for-15-ncdol/

- Dillahunt, Ajamu Amiri. (2019). Interview with Kamal Bell, Sankofa Farms, LLC, Black Perspectives. Retrieved from https://www.aaihs.org/activism-and-agriculture-an-interview-with-farmer-...

- Jones, Van. (2020). 10 steps to save Native Americans from COVID 19 catastrophe. CNN. Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/2020/05/06/opinions/native-americans-covid-19-avoid-...

- Tappe, Anneken. (2020). 30 million Americans have filed unemployment claims since mid-March. CNN Money. Retrieved https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/30/economy/unemployment-benefits-coronavirus...

- Erdman, Shelby Lynne. (2020). Black communities account for disproportionate numbers of COVID-19 deaths in the U.S. study finds. CNN Health. Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/2020/05/05/health/coronavirus-african-americans-stud...

- Dahir, Abdi Latif. (2020). Instead of coronavirus, the hunger will kill us. A global food crisis looms. New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/22/world/africa/coronavirus-hunger-crisi...

- Klare, Michael. (2020). COVID-19’s third shock wave: the global food crisis. The Nation. Retrieved from https://www.thenation.com/article/society/coronavirus-global-food-crisis/

- Cadieux, Kirsten Valentine and Slocum, Rachel. (2015). What Does it Mean to Do Food Justice? Journal of Political Ecology, 22(1)

“Gentrification is affecting a lot of our community members and not just affecting the youth, but also the families. Unless we can find ways to subsidize housing or find way to make gentrification not so dramatic for some of our community members- the youth are not going to be staying in Durham if their parents can’t stay. The Latino family is very tight.” – Eliazar Posada, Community Engagement & Advocacy Manager at El Centro Hispano (ref 324)

“Over the years, the disinvestment in our community has been a process like a storm or a hurricane, it slowly pushed people out. When they say blight, they created the blight, and now they are cashing in on the blight…So we got people in the Southside right now who have been displaced from Hayti, they’re displaced from Few Gardens, they’re displaced from Fayetteville Street Projects, and you can go on and on and on. So they didn’t just face one urban renewal, they’ve faced multiple displacements.” – Brother Ray Eurqhart, long-time Southside resident, union member, and affordable housing advocate (ref 325)

“The engine to rebuild civilization is the farm. If we look through the history of our people, we will see a common theme. The theme is that wherever people of African descent travel, we attempt to reestablish customs and values and build civilization. If we want better health, better housing, better food, better schools, etc., we have to get back to land ownership. Once we have a designated space, we can solve problems that specifically affect our people.” -- Kamal Bell (ref 337)