The Leading Voices in Food

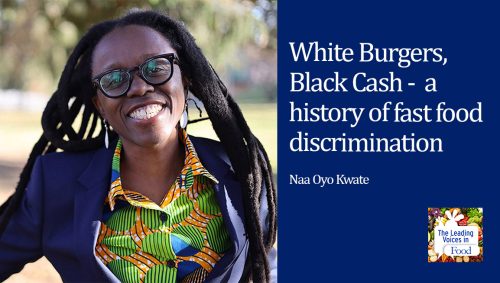

E121: Marcia Chatelain on the Golden Arches and Black America

Today, we’re exploring the intricate relationship among African-American politicians, civil rights organizations, communities and the fast food industry. We’re talking with Dr. Marcia Chatelain, Professor of History and African-American Studies at Georgetown University. She is the author of a fascinating new book entitled, “Franchise: The Golden Arches in Black America.”

Marcia Chatelain is a Professor of History and African American Studies at Georgetown University. The author of South Side Girls: Growing up in the Great Migration (Duke University Press, 2015) she teaches about women’s and girls’ history, as well as black capitalism. Her latest book, Franchise: The Golden Arches in Black America (Liveright Publishing Co./W.W. Norton, 2020) examines the intricate relationship among African American politicians, civil rights organizations, communities, and the fast food industry. An active public speaker and educational consultant, Chatelain has received awards and honors from the Ford Foundation, the American Association of University Women, and the German Marshall Fund of the United States. At Georgetown, she has won several teaching awards. In 2016, the Chronicle of Higher Education named her a Top Influencer in academia in recognition of her social media campaign #FergusonSyllabus, which implored educators to facilitate discussions about the crisis in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014. She has held an Eric and Wendy Schmidt Fellowship at New America, a National Endowment for the Humanities Faculty Fellowship, and an Andrew Carnegie Fellowship.

Interview Summary

Well, let’s begin with this question. Can you tell us about your book Franchise, and why did you believe the story needed to be told?

Well, when I was in graduate school working on my dissertation, which would become my first book, I became more and more interested in issues around the food system and food justice. The film “Super Size Me” had come out while I was in graduate school. And I became more curious about some of the issues around health and nutrition, particularly the disparities along racial lines in terms of access to fast food, as well as marketing and fast food. And as a historian, one of the things I noticed in a lot of the conversations, is that public health practitioners and advocates for healthy eating, rarely contextualized the problems in our food system historically. There was a common sense understanding that some groups of people didn’t have access, and some groups of people were more susceptible to diet related diseases, but I didn’t hear enough people asking, well, how did we get here? And so with franchise, what I really wanted to think about were the ways that McDonald’s, as the leading fast food brand, really pivoted from being a presence in mostly white suburban communities for the first two and a half decades of its existence, to one that became such a presence in African-American communities. And so I wanted to historicize the problems we see today in terms of access to food.

Before you tell us what you found in your historical research, can you tell us how you developed resources for the book?

Oh, thank you for asking that question. As a historian, I love to talk about sources. You know, when I started “Franchise,” the first thing I did was I called McDonald’s, and they have an archivist and their own research entity, like a library, and I contacted them and I said, you know, “I’m a researcher and I’m interested in this history. Can I have access to your archives?” And they said, “No,” which I expected. And so what I started to do is to think really creatively about the various places in which McDonald’s first tried to enter African-American communities, and to think about the leadership of various black organizations during the time. So I started to look outside of the traditional sources for business history and for fast food history. And by centering African-American communities, I found a treasure trove of resources about McDonald’s marketing strategies from the 1960s and how they started to engage with black consumers.

I have a question about marketing in particular I’d like to ask you, but I’ll loop back to that, but let’s tell our listeners what you found mainly in your research.

So, essentially what happens is that McDonald’s is founded by the McDonald’s brother in 1940. And they develop as a Southern California brand, alongside other fast food businesses. But it wasn’t until Ray Kroc creates the McDonald’s system that we know today. Franchises become the way that McDonald’s grows in the 1950s and we start to see McDonald’s confronting the reality of America’s racial climate, such as confrontations over segregation in the South at McDonald’s restaurants.

And then, this period in 1968 shortly after Martin Luther King Jr’s assassination, is when McDonald’s is starting to pivot to African-American neighborhoods because some white franchise owners no longer want to do business in increasingly black communities. This is when the Nixon administration is encouraging something that they are calling black capitalism and is trying to promote black business ownership in black communities. And leaders of the civil rights organizations are trying to determine what their identities and interventions will be after King. And a number of people who were very much formed by that mid-century civil rights struggle start to think about black economic empowerment and development as the next phase. And so all of these forces kind of come together to create an environment in which the fast food industry can capitalize on federal funds and support from the civil rights establishment as well. And the black consumer market is hungering for inclusion in some of the mainstream marketplaces that McDonald’s represents.

Over the years, people, especially the Rudd Center, has done research on targeted marketing of things like fast food and sugar beverages and cereals to people in different demographic groups. And they found a considerable amount of targeted marketing. And there’s been kind of a mix of outrage and lack of surprise on this. Some of the lack of surprise comes from people who better understand the history, like you’re talking about. They will say things like, “you know, there was a time when communities of color were ignored entirely by establishment companies, in both the products they were selling, in their portfolio and also in their marketing, and it actually came as a welcome change when the community started being paid attention to.” But in the context of your work, does that all fit?

Absolutely. So what happened prior to the late 1960s is reminiscent of some of the conversations that were had after the George Floyd summer in 2020, in terms of how far do corporate commitments to inclusion go. How do we think about business as a lever for social change? And so while there had been companies that were marketing to African-Americans throughout the early 20th century, especially during the Great Migration, with the urbanization of African-American communities and a recognition of buying power in those communities, it wasn’t until the late 1960s where you start to see that kind of market segmentation with the specialized advertising, featuring African-American models or celebrities. This is a period in time in which you were seeing the growth of African-American public television programming, shows like Soul! and Black Journal, that are really trying to speak to the concerns of African-Americans. And so after ’68, you start to see this incredible creative industry that is built around marketing to black consumers. And for the first time, it isn’t just commercials that were once designed for white people, and then there are a few black people in the commercials, these are commercials that are trying to really touch upon black cultural markers.

So it sounds like this movement of fast food, led by McDonald’s, into the communities of color was welcome, because what it represented, both in terms of economic development, and then attention being paid to the communities.

Absolutely, and I think it’s really a double-edged sword, because on one hand, people are desirous of this type of inclusion. And it is being sold to communities as this great economic opportunity for people to build wealth, to create jobs, to create community. But the hindsight of 50 years has shown us that all of these things come at an incredibly high price. And in the book, I really like to focus on the varying reactions to what kind of presence McDonald’s should be in black communities. You know, in places in Chicago, people embraced this idea, and community groups actually tried to acquire franchises so they could reinvest in the community. But in other places, people were skeptical of the kind of corporate-social responsibility talk about diversity that McDonald’s was developing the language for throughout the 1970s. And I think the backdrop for all of these conversations and all of these struggles is: can business ever really fully deliver on the promises of racial justice? And I think that the answer is no, because it always comes at such heavy costs to the most vulnerable communities.

I’m expecting that the number of owners of franchises of color has increased over the years. Has that had an impact on the company and the way it does its business?

Well, this is a really fascinating point you raised in this moment. So over the summer, McDonald’s was sued by more than 50 former African-American franchise owners. And there’s a current lawsuit of a current franchise owner, Herb Washington. And they claim that McDonald’s has had a series of policies and behaviors that are racially discriminatory, and that has led to fewer black franchise owners. And so at its peak, it was a little over 300. Now it may be in the 150s, but part of this process of getting African-Americans to franchise McDonald’s was successful, in the sense that, throughout the 70s and 80s, you see the building of economic power among this group of franchise owners. And they take a lot of their profits, and they become incredibly generous with historically black colleges and universities. They prompted McDonald’s to start celebrating the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday. They are the driving force behind some of McDonald’s diversity initiatives within its corporate headquarters, which it was lauded for throughout the 80s and 90s. But these types of changes are sustainable to a point. They are corporate activities that, ultimately, shut out the people who, again, are most needing structural change, and that’s the black and brown workers who are working at the fry stations, who are making burgers, who are ensuring that people get fed in the stores. They’re very much cut out of this vision as a force for good for racial justice.

Now, I’m going to ask you a question that’s more economic in nature. Here’s the context. With programs like SNAP, where vast amounts of money are flowing out from Washington into communities, so people have food assistance that they really need desperately, there’s concern that too little of that money remains in communities, that it just flows through, as people might leave the neighborhoods to go to places like Walmart or Kroger to buy their foods. And so there’s a real missed opportunity for economic development going on. What do you think about McDonald’s? Do you have any sense of how much of that money remains in the communities? Tell me what you think about that.

Well, this is an interesting place in which you see the operation of race in the context of a multinational corporation. So one of the reasons why this lawsuit emerged last year and there were different versions of similar lawsuits and similar claims, since the early 1970s, that McDonald’s essentially restricts African-American business people to doing work in hyper-segregated neighborhoods. And this is important, because part of the sell of this idea in ’68 was that black franchise owners would be like local business people, right? They know the community, they’re connected, they’re invested, they’ll employ people that they know in the community and it’ll have great rewards. But part of that strategy means that there has to be a level of exclusion of those business people from expanding into white neighborhoods or neighborhoods with different racial backgrounds. And part of the argument that black franchise owners make is, the name of the game is volume. And so for us to really keep up with our white peers, we should be able to get a whole bunch of stores in different types of neighborhoods, with different types of operating costs, and we could really profit from it, but McDonald’s, they alleged, keeps them from doing that.

And so when you talk about local impact and local dollars, one of the problems of fast food is that a good portion of the revenue goes way out past the community, because after you talk about the low wage jobs that it provides, and maybe some of the philanthropic efforts, on the local level, a good portion of profits are going to franchising fees, back to the national headquarters. A good portion of the advertising fund that franchisees have to pay into are going to advertising firms in Chicago and New York City and Los Angeles, that aren’t necessarily in the local communities. And the supply chain that fast food relies upon are from vendors and suppliers that are all over the nation, and unlikely to be locally sourced. And so this was one of the critiques in the 1970s, and I think the critique holds today, that fast food does not really circulate money in the local economy, because it is not a local small business, even though there’s some aspects of franchising that might mirror that.

That is fascinating. And so when one calculates the ultimate impact of a place like McDonald’s on the community, there’s the nutrition impact, to be sure. There’s the loss potential for economic development within the community, but they’re all the sorts of historical reasons that made this possible, and even desirable in the first place. But in your own mind, given that you’ve thought about this so thoroughly, how do you balance all of this?

Well, I think that this is a cautionary tale about bad ideas, well-intentioned bad ideas, and the sense that we could rely on the private marketplace to mediate the problems of the public good caused by racism and inequality is not sound thinking, it’s not sound policy. What it is, is a reflection that communities that are vulnerable are often given constrained choices for survival and for something that mirrors advancement. And so it’s kind of strange to think that, in 1968, after all of the grief over the loss of Dr. King, and all of the unfinished business of the war on poverty, of the Johnson administration escalating war abroad, and poverty at home, how is fair housing going to be delivered? The failed promise of school integration. So you have a really, really long list of reasons why people are deeply aggrieved, and the solution comes, well, maybe people could open businesses? Maybe a franchise could come into your community? And this doesn’t respond to any of the reasons why people were crying out in so much pain. And for me, it’s really hard to see that playbook re-emerge in 2020. You know, in the middle of a global pandemic and a crisis of racial justice, you hear some of the similar things. I was just on a call recently, where someone said, you know, “After the George Floyd summer, we committed our company to more investment in black business.” But the reality is that there are nearly 2 million black-owned businesses in the United States. Very few of them have the size, scale, or capacity to provide incredible jobs, and the volume of jobs necessary to really help rebuild communities. And so I think that, if anything, researching this book just made me more certain that big state solutions are the only ways we get on the other side of injustice, and that includes food injustice.

Well, this has been fascinating. So let me end by asking a question about what we can learn from the history of fast food. So what do you think the fast food can teach us about food policy overall in the US, and how do you believe fast food has shaped the relationship to food?

Well, I think that what we need is an end to what I would call passive subsidies for the industry. Because when we think about the fact that we can get this type of food so cheaply and so quickly, then we know that there’s a series of public policy failures all along the road to it, whether it is subsidies on corn for high fructose corn syrup, whether it is the lack of a federal minimum wage that allows low wage work to continue, whether it’s the fact that we have a lot of the smaller… McDonald’s doesn’t fit in this category anymore, but some of the smaller fast food franchises that are qualifying for small business loans. And as a result, this becomes a funnel for minority owned businesses, which are more likely to happen in hyper segregated communities. And so the incentives for opening other types of businesses are fewer than fast food. We have all of these reasons why this problem persists. And unfortunately, we live in a cultural context in which the people who consume the food are blamed for all of the problems and not the structures that allowed this food to become available. And so I think that if we really are serious about health and nutrition and all of the complicated issues associated with fast food, then we have to stop allowing fast food to set the tone of the way we live. A lot of people, when I was on the road for this book on my book tour, would say, you know, “This is why I advocate nutrition education or gardening,” and all of these things. And I said, “These are great, but we have to ask questions about the quality of people’s lives.” All the access to fresh food doesn’t matter if a person can’t pay an electric bill and keep the refrigerator running. And all of the lessons about nutrition and how to prepare food mean nothing, if people are working multiple jobs and don’t have time to prepare food.

The reality is that fast food is a rational and reasonable choice for good portion of Americans, because of the quality of life that people are forced to have, because of poverty and being part of the working poor. And so if we are serious about this, then we need to not let fast food dictate the fact that consuming a lot of calories very quickly makes perfect sense in a culture that people are stretched so thin.