There are deep racial and economic food disparities in every community in this country. Yet, with all the many ways communities come together to try to address these disparities, they usually miss a fundamental component. Inequity is by its very nature, historic, and flows from generations of policies, institutional actions, and individual decisions that have privileged some people at the expense of others. Although there is excellent scholarship on structural inequality and the inequities that result from it, as well as powerful oral traditions and lived testimony of its impacts, most of this history is hidden to the average person and largely absent from public dialogues. Critical histories, the ones that highlight stories of oppression and resistance, of privilege and power, do not live in our history textbooks (or if they do, they are far too simplified and sanitized to provide real complexity and meaning). Nor are they prominent in the mainstream media or in our public monuments or commemorations. In their absence, we do not collectively develop the references and critical thinking skills needed to make sense of the deep inequality in our community and to develop the new institutional forms and power relationships necessary to come together and work towards a more equitable future. In so many ways, our collective “not-knowing” has consequences.

There are deep racial and economic food disparities in every community in this country. Yet, with all the many ways communities come together to try to address these disparities, they usually miss a fundamental component. Inequity is by its very nature, historic, and flows from generations of policies, institutional actions, and individual decisions that have privileged some people at the expense of others. Although there is excellent scholarship on structural inequality and the inequities that result from it, as well as powerful oral traditions and lived testimony of its impacts, most of this history is hidden to the average person and largely absent from public dialogues. Critical histories, the ones that highlight stories of oppression and resistance, of privilege and power, do not live in our history textbooks (or if they do, they are far too simplified and sanitized to provide real complexity and meaning). Nor are they prominent in the mainstream media or in our public monuments or commemorations. In their absence, we do not collectively develop the references and critical thinking skills needed to make sense of the deep inequality in our community and to develop the new institutional forms and power relationships necessary to come together and work towards a more equitable future. In so many ways, our collective “not-knowing” has consequences.

Local History Matters

Creating new histories is the first step in a process of truth and reconciliation that is needed in every place in America, and at every level of governance and community life. New public narratives and counternarratives need to be sought out, unveiled, and discussed. To share these histories is both a process of reckoning with the past and of reorienting how we think about change. As we seek true food justice and more equitable food systems, it is necessary to tell different stories about how we got here, and to wrestle deeply with the legacy of colonialism, white supremacy, and a food system that relies on the exploitation of workers, animals, and the earth. In this endeavor, it is important to recognize that inequality is a relationship, whereby some people are systemically advantaged and others disadvantaged over the course of generations. However, a person or a community cannot be defined solely in terms of victimhood or deprivation, and so this narrative highlight the acts of individual and collective resistance, contribution, and humanity of groups that have been historically marginalized.

With that in mind, the values of a local critical history are worth acknowledging. While we are all influenced by broad political, economic, and cultural systems, we all live locally. Hence, a local history has the ability to highlight the significance of individual and institutional actors and key moments of agency. A local history also illustrates how macro-level forces are both shaped and reshaped by community-level factors, such as community-based organizations, individual networks, and interpersonal connections. Further, putting this history into a local context builds a new set of resonant shared narratives. When history is grounded in the land, neighborhoods, institutions, and people we know, it deepens our attention and emotional response.

Insight Beyond Durham

Insight Beyond Durham

While this is a story about Durham, most places in the U.S. will have similar experiences of the core themes shared within. We intend this history to travel widely across Durham, but also want it to spark conversations and commitments for other communities to follow suit and do their own critical investigations of how we got here. We also recognize that no historical account is ever complete, and hope that this work will be expanded upon and added to in the years to come. Lastly, we ask all who may read this, who are we as history makers? And what legacy are we leaving for the next generation? There are no easy answers, but there is power in the asking.

This snapshot of Durham's Food History, completed in 2020, was developed as part of the Durham Food Justice Project. This report was researched and written by historian Melissa Norton. An abridged version was also created as a podcast, with historical quotes read by contemporary voices.

Info Resources

Executive Summary

This report is an exploration of Durham, North Carolina’s history through the lens of food, agriculture and land. The goal of this project was to uncover the impact of social policies on Durham’s various communities over time. This research identified compelling evidence of systemic inequity in policy and policy implementation that helps to explain the lived realities of Durham’s communities today. The author presents Durham's food history through the following six themes:

- Power & Benefit

- Land & Ownership

- Access to Capital & Resources

- Workers Rights & Compensation

- Globalization & Consolidation of Food Systems

- Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on the Food System

Established Sustainable Food Systems Before First Contact (Pre-1500)

For thousands of years Indigenous Nations lived free on the land. Their skilled stewardship of the land was guided by ethics including moderation, reciprocity, restraint, celebration and gratitude. Over 200 foods were domesticated by Indigenous Nations. For these peoples, land was not a commodity to own and extract from, but earth to be in relationship with as a part of the community. The land that today comprises Durham County is the ancestral home of the Occaneechi, Eno, Adshusheer, and Shocco.

European Colonizers Create Wealth Through Stolen Land and Stolen Labor (1600-1868)

The colonization of what is now called the Americas was a specific type called “settler colonialism.” English colonists first came to what is now North Carolina to start the failed Roanoke colony in in 1585, but permanent settlement did not begin until the late 1600s. By teaching colonists how to forage, clear land, what seeds to plant, and how to select and care for crops, Native Peoples contributed to colonists’ early survival. However, the culture of welcome clashed sharply with the culture of conquest, theft, and subjugation, and the sovereignty and autonomy of Native Peoples, and the land on which they lived, was immediately threatened.

Sharecropping, Black Land Acquisition, and White Supremacy (1868-1900)

The Civil War effectively ended in April 1865, when Confederate Joseph E. Johnston surrendered to William T. Sherman at Bennett Place in Durham County. The Union’s defeat of the Confederacy resulted in massive societal change and opened up a brief time of tremendous potential for reform and change. During the period known as Reconstruction (1865-1877), the Federal Government maintained a military presence in the South and went about setting the conditions by which southern states could return to the Union. Among a host of political, social, and economic exigencies, was the question of what to do with the nearly four million formerly enslaved people who were freed with no land, jobs, money, or rights of citizenship.

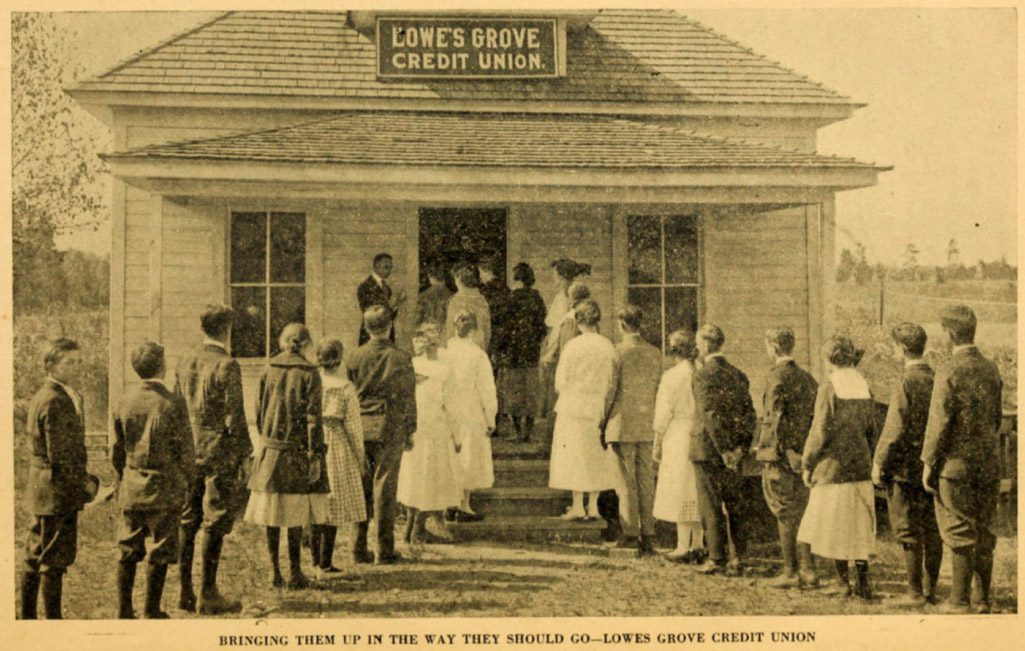

Urbanization & Upbuilding Black Durham (1900-1950)

While Durham County was still largely farmland, the first decades of the 1900s saw incredible urban growth as the city’s population swelled from less than 7,000 in 1900 to more than 60,000 in 1940. The rapidly expanding city came of age during the Jim Crow era (1896-1964), a time defined by a racial caste system shaped by both laws and social customs. The term Jim Crow comes from a popularized caricature of Black people performed by white actors in blackface in the 1800s. In North Carolina, a series of laws were adopted that dictated racial segregation of nearly all sites of life, including schools, transportation, and public facilitates.

The Plight of Farmers & The Tools of Dispossession (1900-1950)

At the turn of the 20th century, more than half of the US population were farmers or lived in rural communities. Even in 1920, farmers comprised 50% of the population in Durham County outside the city core. Nearly half of those were tenant farmers. Of Black farmers, approximately 25% owned their own farms. Dramatic changes occur in the food system in the shift from small farms to industrial agriculture. The year 1920 was the peak of Black landownership and number of Black farmers in this country, but through both legal and coercive means, those numbers dropped dramatically in the following decades

Civil Rights & The Urban Tools of Dispossession (1920-1970)

The patterns of dispossession and exclusion in Durham’s rural areas had their urban counterparts. Racial discrimination by institutions at the federal, state, and local level, combined with individual prejudice, ensured that homeownership, access to capital, and neighborhood-level investments in the city would favor white people throughout the 20th century. These policies and practices had deep implications for food security. From 1900-1964, social relations in Durham were rigidly shaped by Jim Crow laws and customs, which dictated segregation of schools, transportation, eateries, and public facilities, and outlawed interracial marriage. Lunch counters and eateries were a key site of struggle in the Durham Civil Rights movement. Despite major wins by local organizers, decades of disinvestment in Black neighborhoods and racial discrimination in housing lending results in urban renewal and the destruction of Hayti.

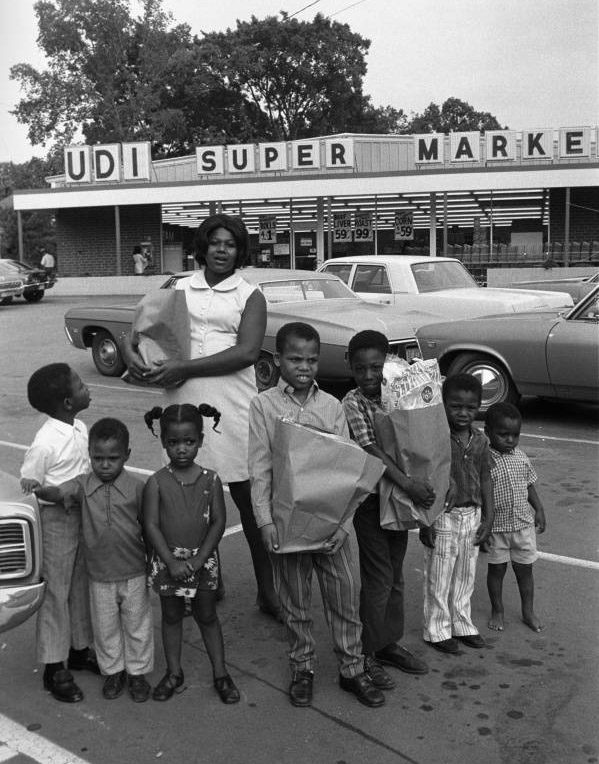

Corporate Power, Food Apartheid, and the New Jim Crow (1975-2000)

In the wake of urban renewal and the building of NC Highway 147, a continued cycle of disinvestment afflicted the central city from the 1970s through the 1990s. Many people who could leave, did. The result was a pattern of both white flight and substantial Black middle-class flight to the quickly expanding suburbs. In their wake, community institutions and businesses such as banks and grocery stores also disappeared. These closures left significant parts of the city underbanked and lacking access to food. At the same time, a huge economic shift was taking place in Durham, whereby the unionized, well-paying factory jobs that had employed Durham’s working class for generations began to leave town for good. Farm Bills from the 70s onward encourage industrialization and expanded consolidation and corporate control of of the food system. The ‘war on drugs’ causes a spike in incarceration with deep consequences for food security. Federal food programs and local non-profits help many, but are unable to meet Durham’s food needs.

Gentrification & the Future of Food Justice (2000–2020)

In the 21st century, a new set of dynamics in the increasingly urbanized Durham landscape present new challenges for food justice. What is often described as ‘gentrification’ is the latest in the legacy of involuntary displacement of people of color in Durham dating back to the Eno and Occoneechi. Indeed, the colonial worldview and the “frontier” mythology pervade how gentrification is talked about in many spaces. Words and phrases such as “urban pioneers” and “trailblazers” to describe the predominantly white and wealthier newcomers in historically disinvested areas described as “burgeoning,” “up and coming,” or even the “wild wild west.” This language pervades the popular press, real estate advertisements, and colloquial conversations, particularly among those with race and class privilege.

Conclusion

The final stage of this report occurred in conjunction with the COVID 19 pandemic that has opened up the existing fault lines of racial, economic, and inequities in the food system to unprecedented levels. The COVID 19 pandemic has already, and will continue to, shape every aspect of our social, economic and political lives moving forward. Even now, there is a growing understanding that new inequities are developing in Durham at an alarming rate.