Durham Food History

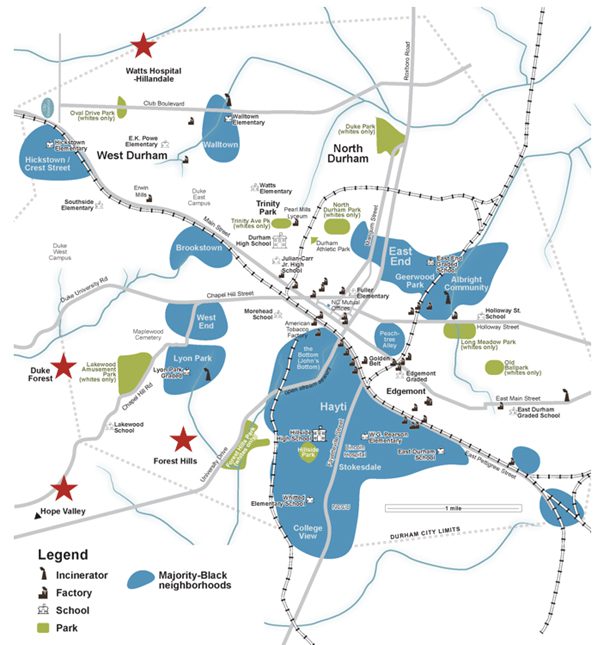

The patterns of dispossession and exclusion in Durham’s rural areas had their urban counterparts. Racial discrimination by institutions at the federal, state, and local level, combined with individual prejudice, ensured that homeownership, access to capital, and neighborhood-level investments in the city would favor white people throughout the 20th century. These policies and practices had deep implications for food security. From 1900-1964, social relations in Durham were rigidly shaped by Jim Crow laws and customs, which dictated segregation of schools, transportation, eateries, and public facilities, and outlawed interracial marriage. Although North Carolina did not legislate housing segregation, other tools of discrimination developed to ensure the neighborhood color line in Durham and in cities across the country.

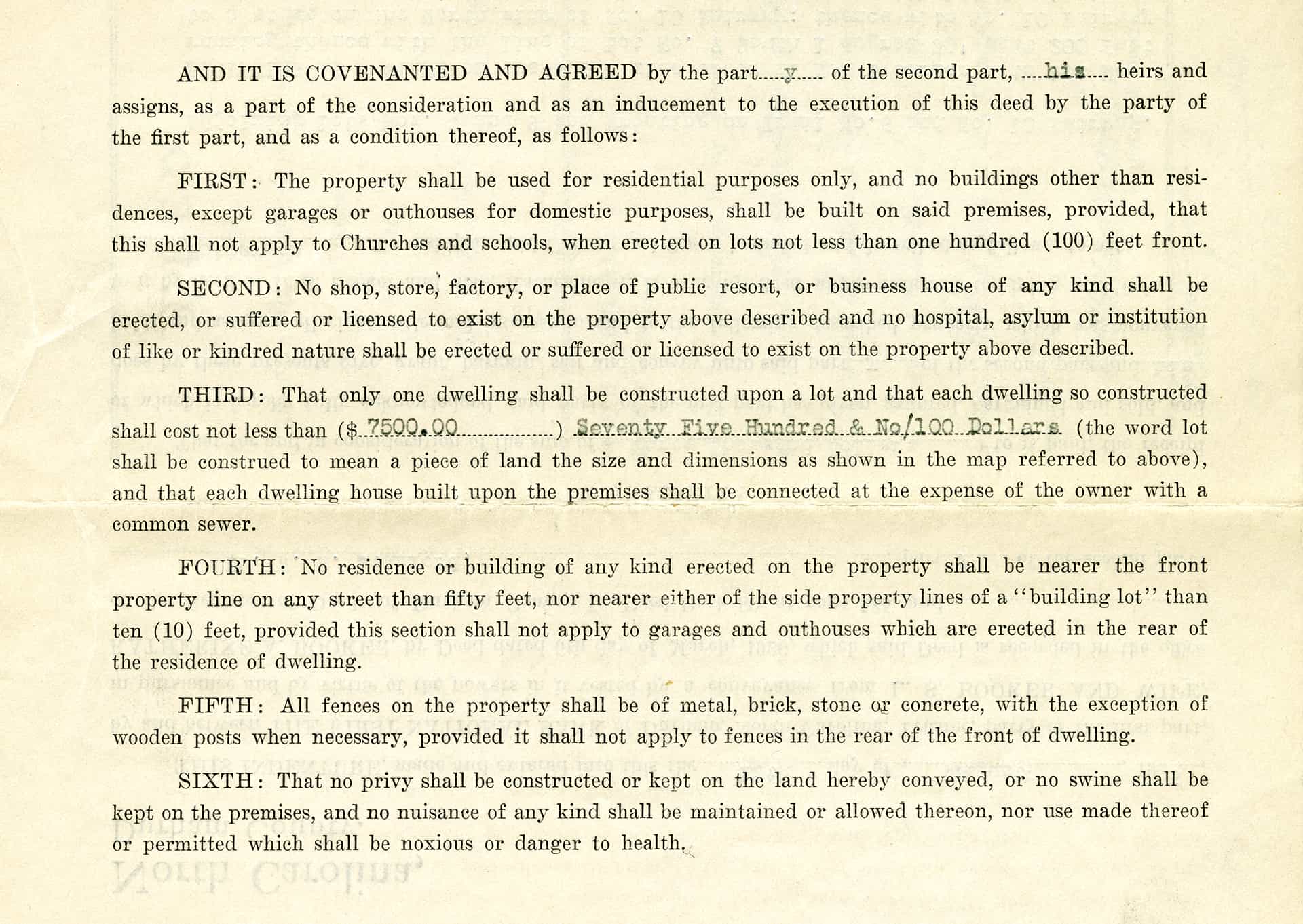

As early as the 1920s, new suburban developments in Durham required white buyers to agree to a list of conditions attached to the deed of the land and home. These “deed restrictions” included an explicit prohibition against Black ownership or residence in the homes, except as domestic servants. Called “racial covenants,” this practice was legal until 1948, and existed in Durham neighborhoods such as Forest Hills, Hope Valley, Duke Forest, Watts Hospital Hillandale, Glendale Heights, and more. Some deed restrictions also dictated a minimum size of housing and lots and prohibited multifamily housing, ensuing class segregation as well.190-191

Local real estate agents adopted the ideology that racial and economic homogeneity were necessary to maintain neighborhood property values and stability. As a result, they directed clients only to neighborhoods that matched their racial and economic background. This was an industry practice known as “steering.” The National Association of Real Estate Boards Code of Ethics was explicit about the role of real estate agents in maintaining segregation, stating that: “A realtor should never be instrumental in introducing in a neighborhood…members of any race or nationality…whose presence will clearly be detrimental to property values in the neighborhood.” This industry guidance remained in effect until 1950. 191-193

Although Black people represented a steady third of the population in Durham between 1900-1950, Black Durhamites had no elected political representation in local city government until the late 1950s. This lack of representation contributed to racial discrimination in the distribution of public amenities and nuisances. For example, white neighborhoods had far more amenities like public parks and received public infrastructure such as water, sewer, and paved roads much earlier than Black neighborhoods. Public nuisances like trash incinerators (used to burn the city’s trash before the use of landfills) were all located in Black neighborhoods. This impacted the quality of life, property values, and incentives for investment in Black neighborhoods.194

Local patterns of discrimination were institutionalized on a national scale as the federal government created a host of new housing programs in the mid-20th century. It began during the Great Depression in the 1930s, when the federal government assessed that growing homeownership opportunities was one of the best ways to expand the middle class and help stabilize the economy. To prepare the government to enter the housing industry, federal agents from the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) were dispatched to 228 cities across the country, including Durham, to work with local real estate agents on ‘neighborhood securities maps.’ These maps used a color-coded system to rate neighborhoods according to levels of risk for lending. Green areas were considered the most stable, then blue, yellow, and the areas deemed unsuitable for lending were colored red- which is the origins of the term “redlining.” In Durham, and in every city the country, the redlined areas were home to people of color and the poorest white neighborhoods. The reasoning deployed in the ratings was explicitly racially discriminatory. Black neighborhoods, mixed-race neighborhoods, and those at threat of ‘invasion’ were all redlined. The area descriptions for each map also noted the local presence, or lack thereof, of public amenities and the quality of housing.195-196

The HOLC securities maps served as a model for both private and public lenders from the 1930s onward. On the private side, HOLC maps were widely distributed amongst banks, where they were used to inform lending decisions and as a template for locally generated discriminatory securities maps. On the public side, the HOLC rating system shaped the lending practices of the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), created in the Housing Act of 1937, and a major new housing program from Veterans Administration, authorized by the Serviceman’s Readjustment Act of 1944. These two programs completely reshaped the residential housing market in the United States. The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, commonly known as the GI Bill, made mortgages available to millions of WWII veterans with little to no down payment and very low interest terms because the loan was insured by the government. The majority of these homes were located in the new suburban developments occurring across the country, which were also largely financed through the federal government. However, with discriminatory lending guidelines and restrictive covenants against potential Black buyers, these homeownership pathways largely excluded the one million plus Black World War II veterans. Moreover, the GI Bill did not issue home loans on the reservations of Native Peoples, which excluded many Native veterans from homeownership opportunities. The same patterns of discrimination were true of the FHA. Between 1935 and 1968, less than two percent of federally insured home loans were for Black people. As a result of these policies, people of color were systematically denied the same crucial opportunity to build wealth and stability through homeownership as white people.197-200

All of these layers of housing discrimination occurred during the Jim Crow era, where one of the most entrenched racial taboos was the prohibition on interracial dining. Although most white people in Durham regularly ate and celebrated food prepared by Black cooks and chefs, “eating with Negroes…means to most white Durhamites ‘social equality,’ which they contend must not be permitted.” Although most Jim Crow laws were passed in the late 1800s and early 1900s, Durham adopted an official city ordinance banning interracial dining in 1947. The impetus for this ordinance is unknown. However, as Black soldiers returned from fighting abroad for their country in World War II, many felt emboldened to defy Jim Crow customs at home. This dynamic may have prompted new segregation laws.200-201

Oral histories and other historical accounts reveal how Black Durhamites resisted, sidestepped, and protected each other against these prohibitions in various ways. Some independent Black businesses, those not reliant on white patronage, ignored interracial dining laws. Unwilling to be treated as second class citizens, Black community leaders shunned invitations to interracial events or meetings that involved food. These leaders noted the impact of interracial eating taboos on Black political and civic engagement. Black parents tried to shield their children as long as possible from the indignities of Jim Crow dining rules.

People who did not fit into the Black/white racial paradigm found themselves in the crosshairs of Jim Crow contradictions. In her memoir, Hot Dogs on the Road, Lena Epps Brooker, of Lumbee, Saponi, and Cherokee heritage shares one such story. Her family stopped at a drive-in cafe in Durham’s Braggtown neighborhood on a drive to visit her father’s family in Person County. With a dismissive racial slur, the waiters initially refused to serve the family. Upon hearing that they were Native American, not Black, there was some conference and confusion, but the family eventually got their food. After the incident, Lena and her two younger siblings all refused to eat, and she reflected that “Durham hot dogs were not appealing to us. They were seasoned with meanness and color poison.” 211

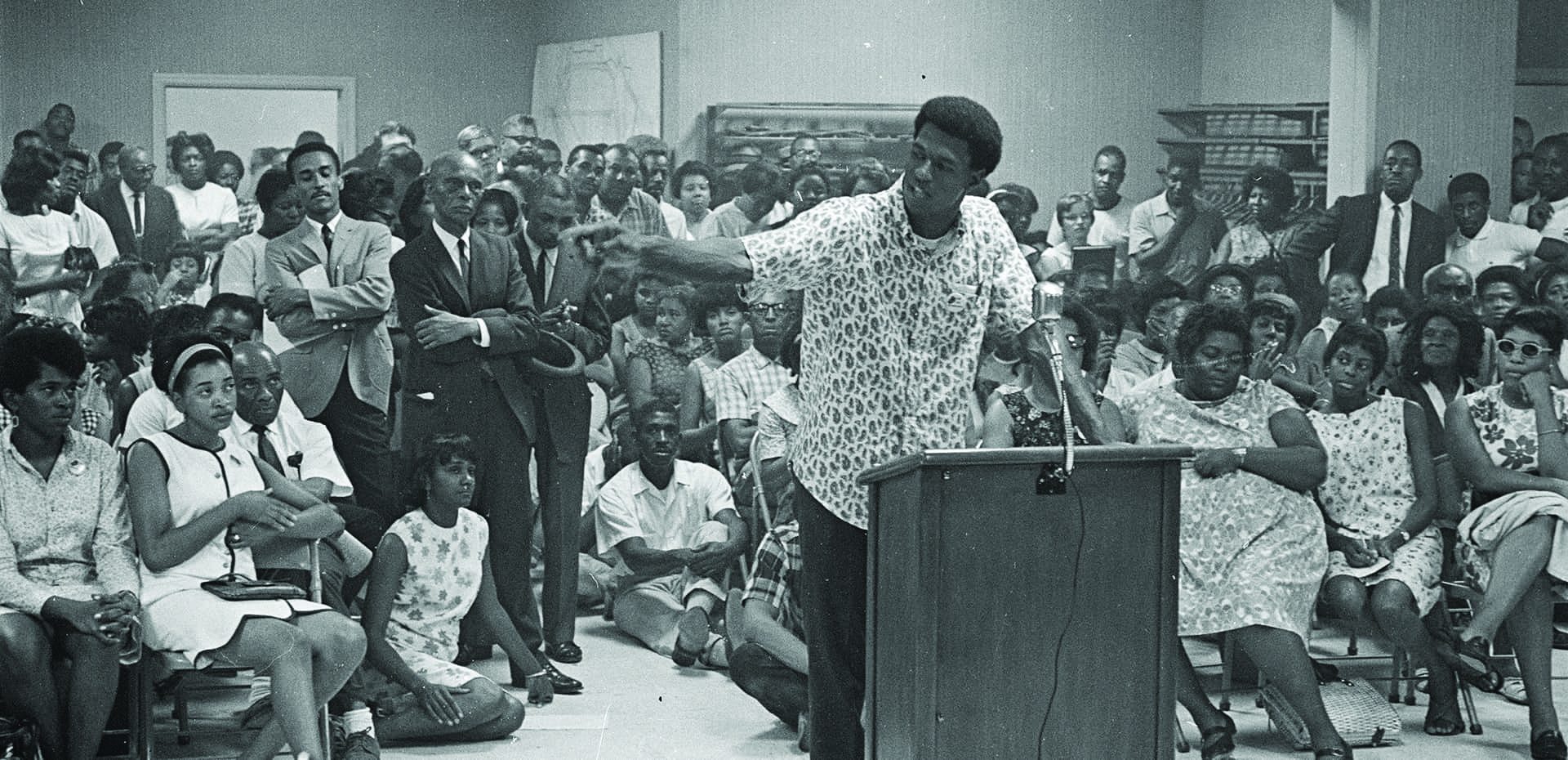

In Durham, lunch counters and restaurants became a key site of struggle during the Civil Rights movement. The civil disobedience at Durham’s Royal Ice Cream restaurant in 1957 was the first sit-in in North Carolina and ignited an era of organizing and direct action. Five years later, a protest to desegregate the Howard Johnsons on Highway 15-501 attracted more than 4,000 people. It was the largest protest in Durham’s history, with protesters chanting “We’re going to eat those 28 flavors” in a defiant reframing of a popular Howard Johnson’s advertising campaign at the time. The struggle to desegregate Durham eateries intensified in 1963 when protesters engaged in sit-ins at six downtown restaurants on the eve of the municipal elections. More than 100 people were arrested and hundreds more surrounded the jail in solidarity. In the weeks that followed, 700+ Durhamites, both Black and white, ran a full-page ad in the Durham Herald pledging support to restaurants and other businesses that adopted “equal treatment to all without regard to race.” The mounting public pressure resulted in mass desegregation of Durham eateries by the end of the year- in advance of the 1964 federal Civil Rights Act that legally ended segregation.206

Black-owned businesses helped support the Civil Rights Movement by providing food to protestors. As Hayti neighborhood restaurateur Peggy Tapp of the Chicken Hut recalls: “We had a lot to do with the sit ins. Fed the CORE folks. Had dealings with all of them. Took food to the jailhouse, and out at Duke University during the sit-ins.” Black women in Durham also played a special role in the Civil Rights Movement. Women showed up in greater numbers to demonstrations, raised money, advised youth groups, coordinated activities, and fed protesters in a show of love and solidarity. This included Mrs. Humely and Mother McLaurin, two cafeteria workers at North Carolina College who made sandwiches for jailed student protesters. As described by historian Christina Greene, “they [Humely and McLaurin] were not simply doing ‘women’s work’ but were literally nurturing the freedom movement.”210-211

Although civil rights wins brought about new political, economic, and social opportunities for Black people, desegregation was not a boon to Black businesses. Segregation, with all its indignities, had fostered a strong sense of racial solidarity and a parallel Black economy. This was reduced as a broader set of options became available to Black consumers. As Andrea Harris from The Institute, a Durham-based nonprofit focused on minority economic development reflected: "With integration, the marketplace was opened. [Before that], a lot of black businesses operated in what I call a sheltered market environment--because you are meeting needs of people who could not buy these products or services in the larger marketplace. With integration, that marketplace was opened." Moreover, whereas Black consumers started patronizing white businesses after desegregation, white consumers did not seek out Black businesses in the same way. As a result, the bottom line of Durham’s Black food businesses were negatively impacted.213

Both nationally and locally, the Civil Rights movement was always clear to link the issue of racial equality with economic opportunity. At the time of his assassination, Martin Luther King was working with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference on a Poor People’s Campaign, to elevate the intersection of these two issues. Civil Rights advocacy, as well as books and exposes about living in poverty such as “the Other America” by Michael Harrington led President John F. Kennedy and then Lyndon Johnson to declare a “war on poverty” in the early 1960s. This war entailed a host of new social welfare policies and programs that became known as “The Great Society.” Reforms included the expansion of healthcare through the creation of Medicaid and Medicare (Social Security Act 1965), adoption of the Title I program that provided additional funding to high-poverty school districts (Elementary and Secondary Education Act 1965), and the passage of the Food Stamp Act of 1964. The food stamp program was implemented in Durham County in 1966, and a decade later, the program was in every county in the country. Researchers heralded “no program does more to lengthen and strengthen the lives of our people than the Food Stamp Program.” Until the early 1980s, the food stamp program received broad bipartisan support.218

Also concurrent to the Civil Rights Movement, was a new slate of federal housing policies that would fundamentally reshape the urban landscape in Durham. Key among them was the Housing Act of 1949, passed during the presidency of Harry Truman with the goal of providing “a suitable home and living environment for every American family.” To accomplish this bold goal, the act included three key provisions. Title I provided funding for clearance of slums and blighted areas in cities, in what became known as “urban renewal.” However, a clear definition of what constituted a slum was never provided. Title II of the act expanded the authorization of the Federal Housing Administration’s mortgage insurance program. Title III was a vast enlargement of public housing funding for 800,000 new units nation-wide.219

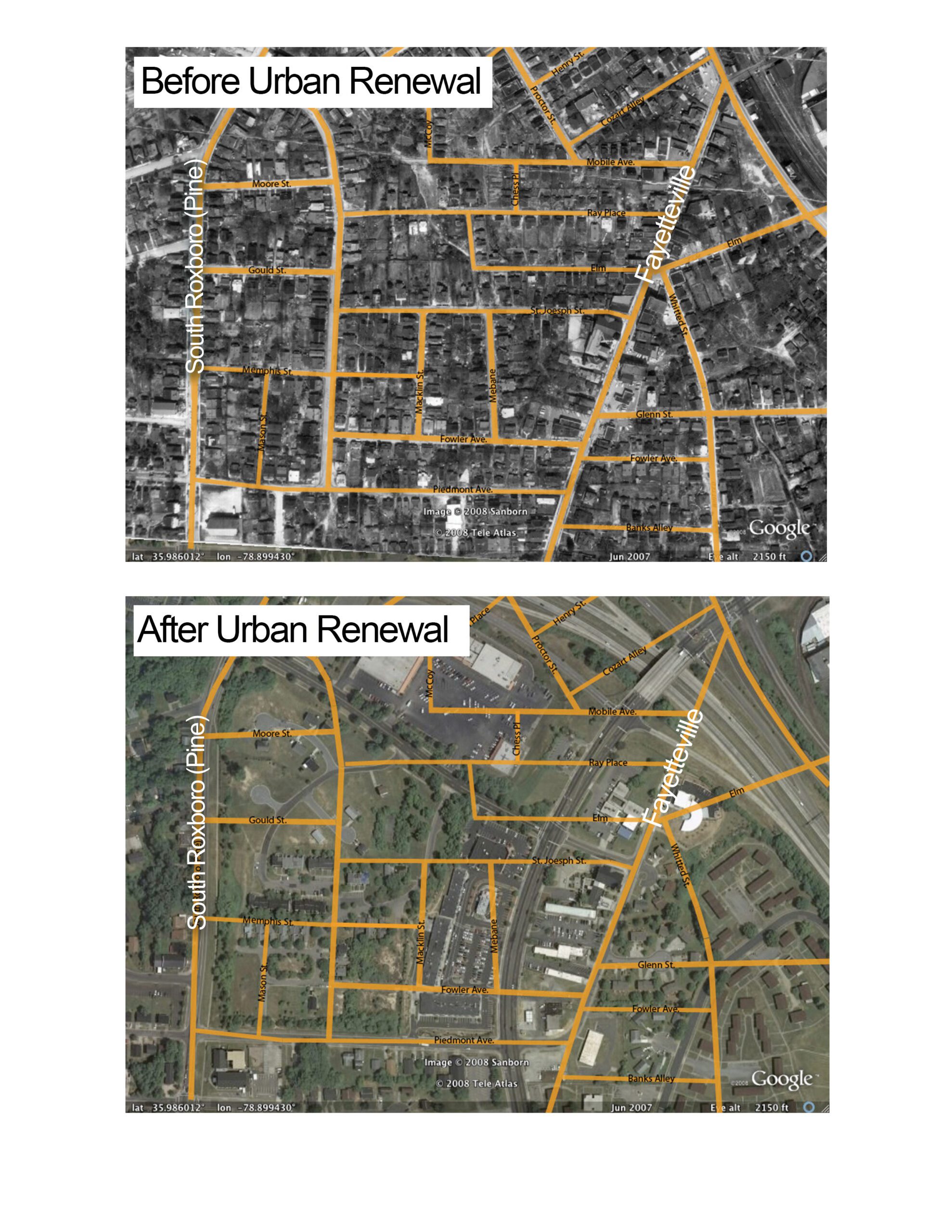

In the late 1950s, Durham applied for a large sum of federal money for a local urban renewal program. There was to be complete local discretion regarding how and where this money was to be used. The city formed a Redevelopment Commission in 1958 and created an urban renewal plan in consultation with the University of North Carolina’s City and Regional Planning Department. In the plan, a large section of the Hayti area, the largest Black neighborhood and home to the majority of Black-owned businesses, was slated for total demolition and redevelopment. This decision occurred in close conjunction with the building of a new state-funded highway, NC 147. The reasons given to focus on Hayti were the presence of rundown buildings, stagnant property values, and public health concerns. Durham planners, city officials, and newspapers used language such as “blighted eyesore” and “economic and aesthetic drag” to describe Hayti and predicted that if something was not done its “tangle of pathologies” would spread to other parts of the city like a virus. This language reflected racist assumptions about dysfunctional Black communities and completely ignored the long history of disinvestment and racial discrimination they had endured. By only focusing on the physical conditions of the area, they disregarded the experiences of its residents and the ways in which place-based community was integral to their survival and well-being.220

During the urban renewal planning stage, the City of Durham was the most powerful decision-maker at the table. In addition to the demolition and clearance of so-called blighted areas, they were also keenly interested in the redevelopment of downtown and clearing the way for the building of Highway 147. White business interests were enthusiastic about building a freeway to relieve congestion downtown and connect to the newly planned Research Triangle Park. They also saw opportunities for private development in the clearance areas and projected an increase in the city’s tax base. To gain support for the project, city officials made three big promises to the Black community: new housing, new commercial development, and major infrastructure improvements in Black neighborhoods. With these commitments made, Black political leaders, in turn advocated for the program. Most working-class Black people knew little about urban renewal or how it would impact their lives, but voted in a bloc with the Durham Committee on Negro Affairs. Thus, when urban renewal went to public vote in a bond referendum, over 90% of Black people voted in support. The most vocal opposition to the project came from Durham’s white working class communities, who saw no benefits to their own communities in the proposed plan. In 1962, the referendum passed by a narrow margin.

Across the country, 2,500 neighborhoods in 993 American cities were dismantled through urban renewal. A million people, disproportionately people of color, were displaced by the program. Locally, the urban renewal program from the mid-1960s through the early 1970s was slow and incredibly disruptive. In the end, the program destroyed much and replaced little. Over 4,000 families and 500 businesses were displaced. This destruction and displacement included a significant part of the area’s food infrastructure, such as grocery stores and restaurants. But the promise of a renewed Hayti and adequate replacements for lost housing and businesses never came. Black leaders and the Hayti community were left stung by a sense of betrayal, and many incurred devastating economic losses.221 When redevelopment did eventually come, it consisted primarily of public housing projects and strip malls.222

Where did displaced Hayti residents go? Some moved to adjacent poor white neighborhoods like Edgemont and East Durham which experienced rapid racial turnover. Many others ended up in new public housing projects. Durham’s first projects in the 1950s were segregated, with Few Gardens for white people and McDougald Terrace for Black people. By the late 1960s public housing had been racialized and was a program almost exclusively for Black people. In the severe housing crunch at the time, public housing was initially a big improvement in residents’ lives, but the promise of public housing as safe, decent, and affordable housing did not last long. Like most places around the country, Durham’s public housing was cheaply constructed, poorly maintained, and quickly deteriorated from normal use. Today, the Department of Housing and Urban Development has more than $35 billion in repair backlogs and deferred maintenance for the nation’s public housing stock. Although the federal government funded public housing construction, the local government made all the decisions about building design and project location. Rather than distributing public housing throughout the city, nearly all public housing projects were clustered in existing Black neighborhoods in southeast Durham. This cut off public housing residents’ access to other parts of the city and reinforced patterns of racial residential segregation.229-230

In reality, the federal government had a two-tiered housing policy for most of the 20th century. On one hand, white people were given unprecedented homeownership opportunities, through long-term, low-interest mortgages backed by the Federal Government, and moved to the suburbs- which were subsidized by the government on nearly every level. On the other, Black people and people of color got public housing that provided no wealth building for its residents. Moreover, Black people were dispossessed of substantial real estate and business holdings through urban renewal and highway projects. The effects of these policy decisions are critical in Durham, and elsewhere, because food insecurity is a result of poverty and the unequal distribution of wealth and power.

Amidst the ravages of urban renewal, a host of new community organizing endeavors took form in Black Durham in the mid to late 1960s. The Carolina Fund, an anti-poverty program started by Governor Terry Sanford, brought paid organizers to Durham’s poor neighborhoods. They knocked doors, listened to the issues facing poor residents, and created a politically powerful federation of neighborhood councils called United Organization for Community Improvement (UOCI). These neighborhood councils convened over food and organized neighborhood cleanups. They protested against urban renewal and advocated for impacted residents. They took on slumlords exploiting the housing crisis in Black Durham with rent strikes and public shaming. In 1967, housekeepers and cafeteria workers at Duke, primarily Black women, organized under AFSCME’s Local 77 union and created demands for higher wages and better working conditions. The next year, Durham’s Black community, responding to the firing of 31 Black employees from Watt’s Hospital, formed the Black Solidarity Committee (BSC). The BSC submitted a list of 88 demands to the Durham Chamber of Commerce and Merchants Association related to employment, education, political representation, and police conduct in the Black community. They organized and sustained a boycott of white businesses for over nine months and ultimately won some of their demands. Historian Christina Greene called this boycott “the longest, most successful, broadest-based protest ever waged by Durham Blacks.”231-232

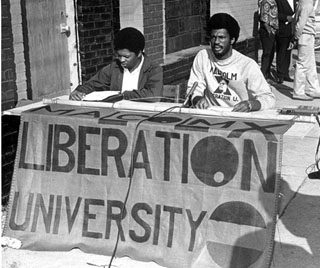

During the same time period in the late 1960s, the Black Power Movement took root in Durham. Perceiving limited tangible gains for Black people in the civil rights desegregation victories, its leaders called for Black self-determination and autonomy. One expression of this movement locally was the formation of Malcolm X University (MXU), an independent higher-learning institution that opened in the heart of Hayti in 1969. Its mission was to provide an ideological and practical methodology for meeting the physical, social, psychological, economic and cultural needs of Black people. The curriculum called for African language study and travel abroad to Africa. Students were required to concentrate studies in one of the fields deemed most needed to sustain a Black nation, one of which was food science. After a year of operation in Durham, MXU moved to Greensboro. One of the attractions of the Greensboro site was that it afforded students space to operate a farm, where they grew vegetables, raised chickens, and learned about various African foodways. The university subsequently closed in 1973, but planted many seeds that would come to bear fruit.233-234

"[There was] always a bunch of church women who would be there for us, hugging us and feeding us and making sure everything was just so. Sometimes you knew ’em and sometimes you didn’t, but you knew somebody was going to take you in their arms when you walked off that picket line. . . there’s no way you can match that kind of contribution.” -- Civil Rights activist Joycelyn McKissick (ref 212)

"The struggle was, at that particular time, the type of people we depended on that supported our business throughout the years, the low income, the poverty stricken, the welfare- these people were the ones who really supported us. It was even a worse time when integration set in. We found out that we as Blacks could go to the hotels and restaurants and sit any place--this set us a little bit behind." -- Peggy Tapp (ref 214)

“Once upon a time some people of Durham were shown beautiful pictures and miniature layouts of a renewed city. These people were led to believe that if they voted in favor of the proposals being offered, they would see new and attractive rebuilding where slums and old second-hand buildings were standing. They were led to believe that they would be justly compensated for their properties and aided in many ways with rebuilding. So, they went to the polls in droves and had a lot to do with voting the proposals into law. Those people didn’t all live happily ever after. Most were unable to survive the trauma of being betrayed, misled, robbed, unjustly treated. Too strong words, you say? Some died, some lost their minds. Some were foreclosed on. Some just went out of business. Some got sick and are still sick. A few, and only a few, got richer. The story is about to end. Promises haven’t been kept yet. Compare, if you will, the appearance of downtown Durham with that of what used to be Hayti, the Black business district. Draw your own conclusions. It must have been a fairy tale.” – Carolina Times editorial, 1977 (ref 228)

“In all licensed restaurants, public eating places, and ‘weenie shops’ where persons of the white and colored races are permitted to be served with and eat food, and are allowed to congregate, there shall be provided separate rooms for the separate accommodation of each race. The partition between such rooms shall be constructed of wood, plaster, or brick or like material, and shall reach from the floor to the ceiling. Any person violating this section shall, upon conviction, pay a fine of ten dollars, and each day’s violation thereof shall constitute a separate and distinct offense.” – The Code of the City of Durham, NC, 1947, C.13, Sec 42 (ref 202)

"There is a place here on Pettigrew St called the Do-Nut Shoppe where whites and Negroes eat together a good bit. It's the Jade Room…We have some interracial meetings there, too. The owner of that place is what we call a 'new era Negro,' who doesn't hold to this segregation business. He's a fine fellow too." -- Louis Alston, Black editor of the Carolina Times, 1950 (ref 203)

"We [the Interracial Committee] meet at the Washington Duke Hotel freely. The other day I was even invited to a luncheon there, but I didn't go. I told them I was busy. Sometimes, I get awfully busy. That's the reasons we don't have more Negroes on boards and things. If they have their meetings in public places without meals, it would be better. I'm kinda' particular about who I eat with too. I lose my appetite pretty quickly around some people.” -- C.C. Spaulding, Black business leader of the North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company, 1950 (ref 204)

“When I was a child, the Durham Dairy was a weekly stop on Sunday evenings as part of our family ‘drive.’ We would park, go in to the counter and then return to the car with our ice cream. After my Father finished his, we would then drive around Durham while the rest of us finished our ice cream. I had no idea as a young child that the reason we took that ice cream to the car was because the Durham Dairy was segregated and being an African American family, we were not allowed to eat our ice cream on the premises. I was shocked to learn as an adult how my parents had been so artful in sparing this ugly truth from me and my younger siblings.” -- Open Durham commenter (ref 210)

"None of it made any sense [Jim Crow], but that had been the way of life, and that's the way the older folk had accepted it. And so, I guess I was one of them who thought, if not us, who? If not now, when? ...So the police officers came, and they asked us to leave. I remember one of them asked me to leave, and I asked for ice cream. And he said, if you were my daughter I would spank you and make you leave. And I said, if I was your daughter I wouldn't be here, sitting here, being asked to leave." - Virginia Williams, member of Royal Ice-Cream 9 (ref 209)

“Well, I think we got something like $32,000 for our business. As I look back on it now— if you’re going to drive a freeway right through my building, the only fair thing to do is to be able to replace that building. In other words, I ought to be able to move my equipment and everything into a building. If they do it like that, you will be able to stand the damage. Now, the Highway Department has a replacement clause in their building but the Urban Renewal had what they call “fair market value” and that won’t replace it. And that’s where the handicap comes…just say you give him $32,000. That probably would have maybe have bought the land or whatever, but it wouldn’t put the building back and everything like that.” – Nathaniel White, former Hayti business owner (ref 226)

“The so-called Urban Renewal program in Durham is not only the biggest farce ever concocted in the mind of mortal man...but is just another scheme to relieve Negroes of property.” - Louis Alston, Carolina Times Editor, 1965 (ref 227)

References

- Penniman, Leah. (2018). Farming While Black: Soul Fire farm’s practical guide to liberation on the land. White River Junction VT: Chelsea Green Publishing

- Durham deed restriction research done by Melissa Norton for Bull City 150, 2017.

- Shelley v. Kramer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) Retrieved from https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/334/1/

- National Association of Realtors. (1924). 1924 National Board of Real Estate Ethics Manual. Retrieved from https://www.nar.realtor/about-nar/history/1924-code-of-ethics

- Denton, Nancy and Massey, Douglass. (1993). American Apartheid: segregation and the making of the underclass. Boston: Harvard University Press, p. 37

- Bull City 150, Uneven Ground exhibit, www.bullcity150.org

- Denton, Nancy and Massey, Douglas. (1993). American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass. Harvard University Press, p. 51-52

- University of Richmond. Redlining in New Deal America. Mapping Inequality. Retrieved from https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/#loc=14/36.006/-7936&city=du...

- Denton, Nancy and Massey, Douglas. (1993). American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass. Harvard University Press, p. 52-23

- Bauman, John, et al. (2000). From Tenements to the Taylor Homes: In Search of an Urban Housing Policy in Twentieth Century America. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, p. 163-179

- Weber, Brandon. (2017). How African American WWII veterans were scorned by the GI Bill. The Progressive. Retrieved from https://progressive.org/dispatches/how-african-american-wwii-veterans-we...

- Caramo, Cindy. (2014). Navajo military veterans struggle with housing. Los Angeles Times (Los Angeles). Retrieved from https://www.latimes.com/nation/la-xpm-2014-mar-08-la-na-ff-navajo-vets-h...

- Wilkerson, Edith. (1950). Pattern of Negro Segregation in Durham North Carolina. Master’s Thesis, Duke University, p. 135

- Gershenhorn, Jerry. (2018). Louis Alston and the Carolina Times: a life in the long black freedom struggle. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, p. 60-88

- Wilkerson, Edith. (1950). Pattern of Negro Segregation in Durham North Carolina. Master’s Thesis, Duke University, p. 139

- Wilkerson, Edith. (1950). Pattern of Negro Segregation in Durham North Carolina. Master’s Thesis, Duke University, p. 139

- Wilkerson, Edith. (1950). Pattern of Negro Segregation in Durham North Carolina. Master’s Thesis, Duke University, p. 137

- Open Durham. (Comment 4/28/2012). Durham Dairy Products. Retrieved from http://www.opendurham.org/buildings/durham-dairy-products

- Brooker, Lena Epps. (2017). Hot Dogs on the Road: an American Indian girl’s reflections on growing up in a black and white world. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, p. 59

- Greene, Christina. (2005). Our Separate Ways: Women and the Black Freedom Movement in Durham, NC. The University of North Carolina Press, p. 62

- Anderson, Jean. (2011). Durham County. Durham: Duke University Press, p. 369-370

- Durham: a Self Portrait, directed by Steven Channing, 2007; Durham, North Carolina, Southern Documentary Fund

- John Hope Franklin Research Center, Duke University Libraries. (1994). Interview with Peggy Tapp (btvnc03036), interviewed by Felix Armfield Durham (N.C.). Behind the Veil: Documenting African-American Life in the Jim Crow South Digital Collection

- Greene, Christina. (2005). Our Separate Ways: women and the black freedom movement in Durham, North Carolina. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, p. 102-103

- Greene, Christina. (2005). Our Separate Ways: women and the black freedom movement in Durham, North Carolina. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, p. 102

- Durham: a Self Portrait, directed by Steven Channing, 2007; Durham, North Carolina, Southern Documentary Fund

- John Hope Franklin Research Center, Duke University Libraries. (1994). Interview with Peggy Tapp (btvnc03036), interviewed by Felix Armfield Durham (N.C.). Behind the Veil: Documenting African-American Life in the Jim Crow South Digital Collection

- Testimony of Robert Greenstein, President, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities Before the House Committee on Agriculture. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Retrieved from https://www.cbpp.org/testimony-of-robert-greenstein-president-center-on-...

- Orlebeke, Charles. (2000). The Evolution of Low-Income Housing Policy, 1949-1999. Housing Policy Debate, 11(2), p. 489-493

- Full text of the Housing Act of 1940. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/law/help/statutes-at-large/81st-congress/session-1/c...

- Bundage, Fitzhugh. (2008). The Southern Past: a clash of race and memory. Boston: Harvard University Press, p. 237-239

- Herald Sun (Durham). Nov. 20, 1958, p. A4

- Herald Sun (Durham). July 27, 1962, p. A1

- Bundage, Fizhugh, (2008). The Southern Past: a clash of race and memory. Boston: Harvard University Press, p. 236-243

- Rice, David. (1966). Urban Renewal: a case study of a referendum. Master’s Thesis, UNC Chapel Hill

- Uneven Ground: The Foundations of Housing Inequality in Durham, NC. Bull City 150 exhibit, 2017

- Fullilove, Mindy Thompson. (2004). Root Shock: how tearing up city neighborhoods hurts America, and what we can do about it. New York: Ballantine Books, (2005 ed.), p. 4

- Anderson, Jean. (2011). Durham County. Durham: Duke University Press, p. 344

- Oral history excerpt in exhibit by Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity, “Durham’s Black Wall Street: Finding Freedom Through Entrepreneurship,” 2019

- Alston, Louis. (1965). Urban Renewal a Farce or Reality. Carolina Times (Durham), p. 2

- Editorial. (1977). Promises, Promises. Carolina Times (Durham)

- Denton, Nancy and Massey, Douglas. (1993). American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass. Harvard University Press, p. 56-57

- Public housing deferred maintenance estimate on HUD.gov https://www.hud.gov/RAD

- Korstad, Robert and LeLoudis, Jim. (2010). To Right These Wrongs: The North Carolina Fund and the battle to end poverty and inequality in 1960s America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, p. 184-185, 193-194, 302-303

- Greene, Christina. (2005). Our Separate Ways: women and the black freedom movement in Durham, North Carolina. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, p.106-107

- Fuller, Howard with Page, Lisa Frazier. (2014). No Struggle No Progress: a warrior’s life from Black Power to education reform. Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, p.101, 107, 110-111