Durham Food History

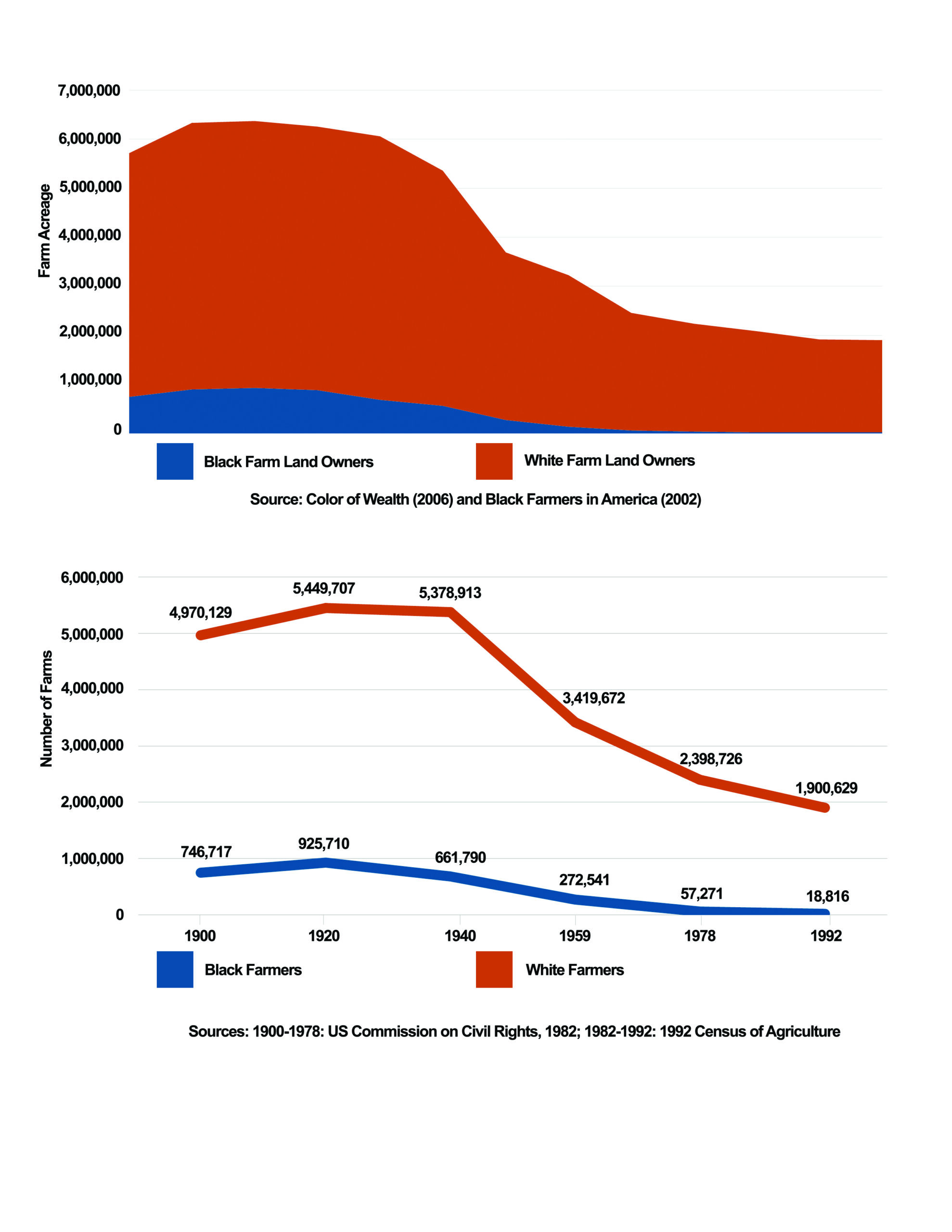

At the turn of the 20th century, more than half of the US population were farmers or lived in rural communities. Even in 1920, farmers comprised 50% of the population in Durham County outside the city core. Nearly half of those were tenant farmers. Of Black farmers, approximately 25% owned their own farms. At this time, farms were diversified enterprises, producing crops and animals together on the same farm in complementary ways. Animals were typically raised with access to the outdoors and fed from the farm, their manure provided valuable natural fertilizer, and most of the farm work was done by human and animal labor.147

Over the next 50 years, profound changes occurred to the food system as it became increasingly industrialized. Industrial agriculture is characterized by specialization (monocultures, selective breeding, factory style practices for raising animals); mechanization (work by machines, expansion of irrigation and transportation systems); dramatic increases in the usage of synthetic fertilizers, herbicides, and pesticides; and consolidation (agricultural production shifting to larger farms). This shift allowed for greater production of lower cost food, on which growing cities like Durham depended. However, productivity gains came at considerable environmental, cultural, and public health costs. In Durham, one-crop farming had long dominated the agricultural landscape. Approximately 75% of cultivated acreage was planted in the cash crops of tobacco, cotton, and corn in 1920. While county farmers grew enough food for their own families, they contributed less and less to the local food supply chain. As a result, Durham residents were increasingly dependent on food sourced from outside of Durham. This was a situation worried local leaders.148

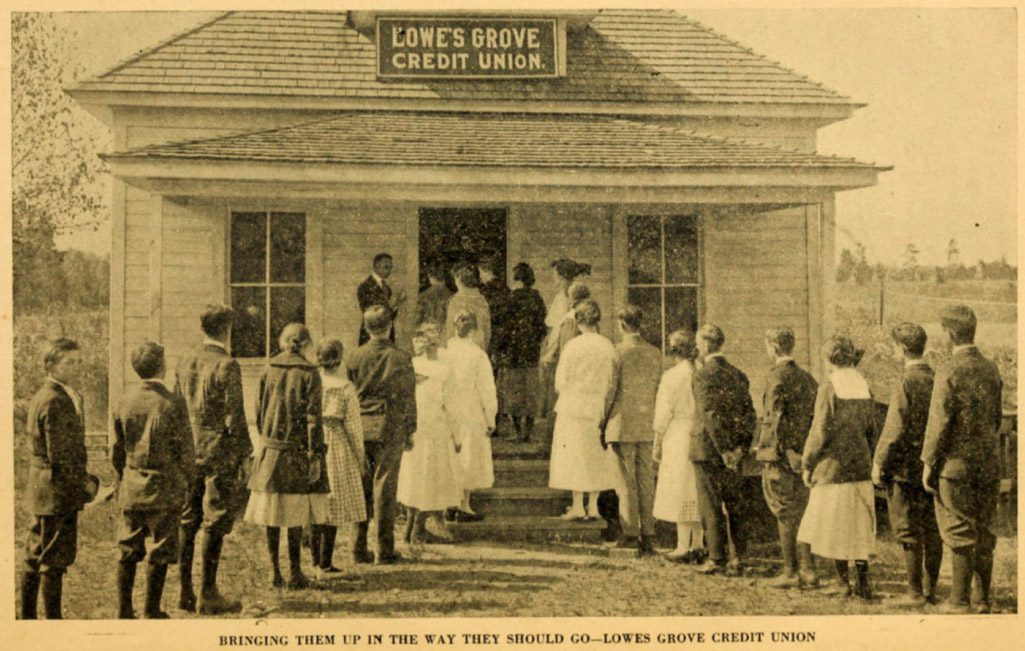

During this time of transition to more industrialized farming, small-scale farming (which predominated in Durham) became an increasingly difficult enterprise due to a depressed economy, exhausted soils, antiquated farming tools, and the prevalence of cash crops. Underscoring these factors for small farmers of all races was the ongoing issue of lack of access to fair credit and chronic indebtedness. As described in a pamphlet called Negro Credit Unions of North Carolina in 1920: “Perhaps the greatest drawback to the average poor farmer, struggling for a foothold on the soil and trying to make a home for himself and family in the community, is the lack of capital. If he buys fertilizer on time, borrows money, or contracts to be carried over the cropping season, it is usually at such a ruinous rate of interest that few ever get out from under its baneful influence. The man who owns a small farm, as well as he who rents one, has long been victimized by the credit system." 149

Responding to the dire need for rural credit on fair terms, white Durham business leader John Sprunt Hill led the effort to get the enabling legislation for credit unions passed in North Carolina. Working with the families of the Lowe’s Grove Farm School, Hill helped establish the Lowe’s Grove Credit Union in 1916. This was the first in a wave of credit unions across the state. A credit union is a type of bank that receives deposits from its members, and which in turn, does loans to members at low interest rates. Members often belonged to the same farm organization, school district, or church, and these early credit unions frequently engaged in cooperative buying programs for its members at reduced bulk rates. The credit union was embraced by Black farmers and workers, particularly in the eastern part of the state, and by the 1940s, North Carolina had more Black credit unions than nearly all other states combined. However, there is no record of a Black credit union in Durham in this time period, perhaps due to the widespread usage of Mechanics & Farmers Bank.150-152

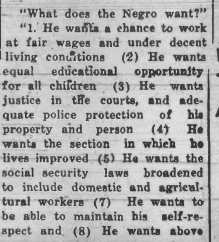

During the Depression, widespread unemployment led to broad labor unrest across the country. Diligent organizing and protests by labor unions pressured President Franklin Roosevelt to initiate a host of reforms that made for the most extensive expansion of the social safety net ever seen in this country. These reforms, passed between 1933 and 1939, are commonly known as the New Deal. However, the benefits of these new programs were not shared equitably across race. Pressure from white southern legislators ensured that agricultural and domestic workers were excluded from new social programs. This included social security benefits and unemployment insurance (Social Security Act, 1935), new labor protection laws regarding the minimum wage (Fair Labor Standards Act, 1938), and the right to organize (National Labor Relations Act, 1935). To put this into perspective, domestic and agricultural occupations employed almost 75% of Black workers in the southern states in the 1930s. The exclusion of these workers was intentional and racially motivated. As explained by historian Ira Katznelson: “Southern legislators understood that their region's agrarian interests and racial arrangements were inextricably entwined…. By excluding these persons from New Deal legislation, it remained possible to maintain racial inequality in southern labor markets by dictating the terms and conditions of African American labor.”176-177

The federal agencies set up to support farmers also expanded greatly during the New Deal. However, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and programs such as the Federal Extension Services (FES) and the Farmers Home Administration (FmHA) each advanced practices and policies of institutional racism. A 1964 study by the Johnson administration found evidence of racial discrimination in every program of the USDA in regards to funding, employment/promotion, and decision-making. The report confirmed that while small farmers were losing out everywhere, Black farmers were segregated and "consistently outside the decision-making process." In the federal office in Washington D.C., the FmHA employed one Black professional and only one Black agent worked in the federal Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation (ASCS) office. The ASCS is a USDA agency that granted loans to farmers, purchased farm products from farmers, administered land allotment programs, and shared the cost of conservation and environmental protection measures with farmers. ASCS discrimination permeated down to the local elected county committees. These committees were dominated by white elite farmers who shorted black farmers on allotments- federal money meant to directly augment farmers’ incomes. The report also verified what many had known for decades, that the Black extension services were "distinctly inferior and provided entirely on a segregated basis," and that despite its funding and oversight role, the USDA "completely disowns responsibility for the way in which the Extension Service is operated."178-179

Discriminatory practices by the USDA continued long after the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, which legally ended racial discrimination in federal programs. In 1980, the North Carolina Black Farmers organization filed a lawsuit against the FmHA charging racial discrimination in farm aid. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission investigated the complaint and found that Black farmers received fewer loans for smaller amounts, were less likely to get deferred loan payment schedules, and more likely to have to agree to liquidation of their property if they defaulted. A subsequent USDA investigation found that Black farmers typically waited 134 days longer for loan decisions and were nearly 30% less likely to get loans approved than white applicants. Cumulatively, decades of discrimination through these programs prevented Black farmers from accessing the capital needed to sustain, adapt, and grow their farming enterprises. The result was massive transfers of both financial resources and land from Black to white farmers.180-182

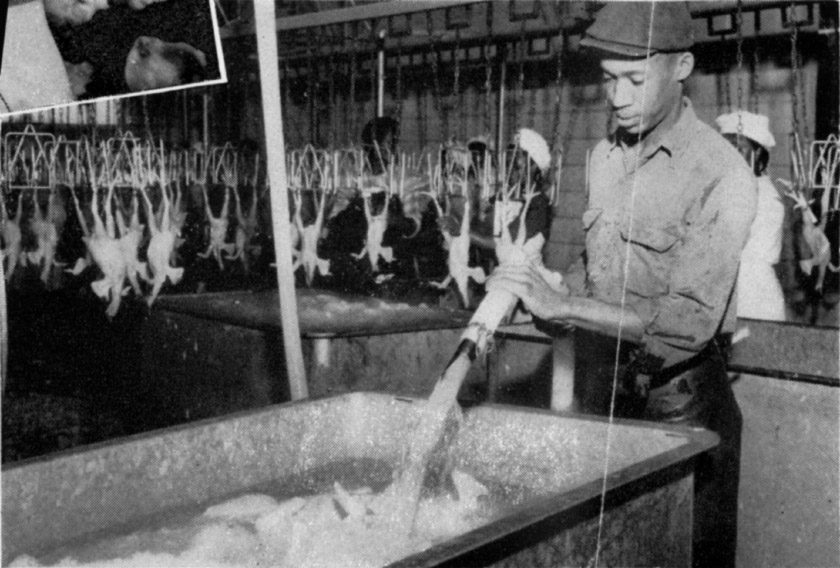

In the 1930s and 1940s food supply chains began to expand geographically with the rise of refrigeration, mass production, better transportation infrastructure, and improvements to preservation techniques. These trends were reflected locally in a new cooperative endeavor called the Farmers Exchange, which opened in 1930 at a large campus just east of downtown Durham. Plans for the cooperative included arrangements for the local sale of chickens, eggs, hogs, sweet potatoes, and other farm produce as well as the infrastructure to ship surpluses to places where prices might be better, thus increasing the market reach for local producers. The Farmers Exchange campus included a cold storage and freezer locker plant for the processing and storage of meat, a poultry plant and hatchery to process and market large amounts of poultry and eggs, and a maintenance garage to service farm equipment. Although the early years are unclear, the Farmers Exchange appears to have served and employed people across race by the 1950s.166-170

The early development of industrialized agriculture corresponded with the Progressive Movement, which spanned the turn of the century through the 1920s. In the agricultural realm, Progressive Movement leaders promoted an ideology of modern progress that prized technology and book learning over the common sense and real world experience on which most farmers relied on. New support services and education programs arose to promote modernization and the agricultural sciences, with the intent to help farm families sustain themselves in this new era. The federal Smith-Lever Act of 1914 established a system of cooperative extension services in each state, connected to the land-grant universities, to inform farmers about current developments in agriculture, home economics, public policy, and economic development. In North Carolina, the original land grant university was North Carolina State University, created through the Morrill Act of 1862. However, NC State only admitted white students, so in 1891 a second land grant university, North Carolina A&T University, was established for Black students. These universities were never funded at equal levels and the state’s extension services flowed primarily out of NC State.157-159

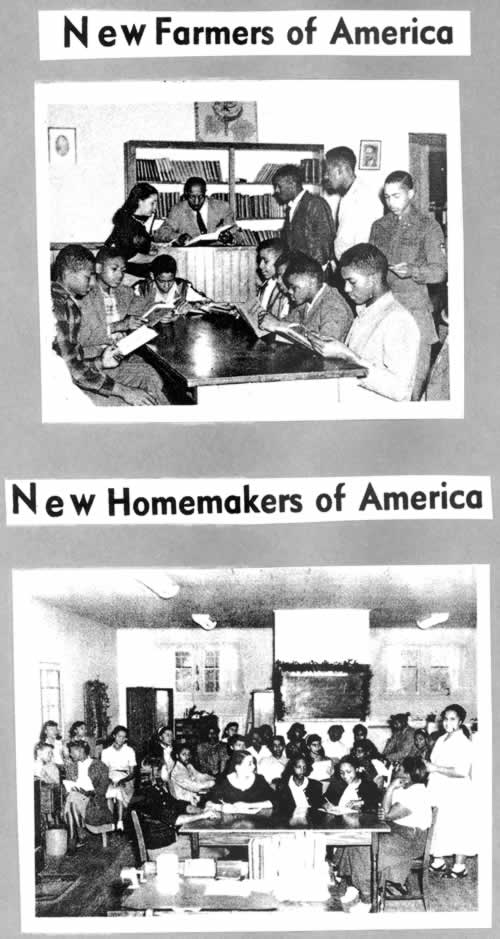

The state extension program operated through county offices. Durham County Commissioners hired the first white home demonstration agent in 1915, followed by a Black home demonstration agent two years later in 1917. Female agents traveled across the rural parts of Durham developing home demonstration clubs for women and teaching skills like food preservation and home economics. Male extension agents educated farmers about nutrient and soil management and techniques such as terracing to reduce erosion. The Durham Cooperative Exchange also ran agricultural education programs to promote youth entrepreneurial and leadership development at Durham public schools in the city and county. Segregated schools had separate programs; Future Farmers of America served white students and New Farmers of America served Black students.160

In Black county schools, extension work was augmented by Durham’s Jeanes teachers, named for the northern Quaker philanthropist Anna Jeanes who funded the program. Beginning in 1915, these women served as tireless community organizers in the county, helping to raise money to build schools, improve public health, and foster various educational opportunities. They were officially tasked with implementing industrial education- practical skills that had the stamp of approval from white funders and the school superintendent. In the Jim Crow era, local white school administrators and the northern philanthropists that supported southern Black education held racist assumptions about what type of education Black people needed. They believed that there was a “lack of civilization” among Black people, and assumed that after leaving school, women would be doing primarily domestic work and men unskilled or semi-skilled labor. However, Durham Jeanes teacher Carrie Jordan reframed teaching subjects such as cooking, gardening, and canning food as measures of individual and community self-sufficiency “that could help Black students improve their lives- rather than simply learning to be cooks and maids for white people.”161

Beyond the financial uncertainties, farm life was hard work that followed the rhythms of seasonal and agricultural cycles. There were few material luxuries. The farm family functioned as an economic unit wherein each person had jobs to fulfill. Men did the heaviest and most public work of plowing the fields, settling up, and taking the product to the market. Women and children performed lighter tasks such as making seedbeds, weeding, transplanting. Women also did the household work, including laundry, food preparation, and child care. All family members did their part to feed, milk, and slaughter animals. In Durham, there were special times of year for communal rituals such as berry picking, corn shucking, and peach canning. A connection to the land and the presence of close-knit families and communities provided a sense of grounding and joy for many, but was stifling and monotonous for others. For both personal and economic reasons, the draw of perceived opportunities in the city or ‘up North’ were strong for many, and a steady stream of migrants left the land. Black Durhamites that left for cities in the northern and western parts of the country were a part of a migration flow that included six million Black people from across the South between 1917 and 1970. This massive domestic population movement is known as the Great Migration. Those who stayed on the land found themselves caught between traditional farming culture and an increasingly modernized urban world.153-154

The early development of industrialized agriculture corresponded with the Progressive Movement, which spanned the turn of the century through the 1920s. In the agricultural realm, Progressive Movement leaders promoted an ideology of modern progress that prized technology and book learning over the common sense and real world experience on which most farmers relied on. New support services and education programs arose to promote modernization and the agricultural sciences, with the intent to help farm families sustain themselves in this new era. The federal Smith-Lever Act of 1914 established a system of cooperative extension services in each state, connected to the land-grant universities, to inform farmers about current developments in agriculture, home economics, public policy, and economic development. In North Carolina, the original land grant university was North Carolina State University, created through the Morrill Act of 1862. However, NC State only admitted white students, so in 1891 a second land grant university, North Carolina A&T University, was established for Black students. These universities were never funded at equal levels and the state’s extension services flowed primarily out of NC State.157-159

The state extension program operated through county offices. Durham County Commissioners hired the first white home demonstration agent in 1915, followed by a Black home demonstration agent two years later in 1917. Female agents traveled across the rural parts of Durham developing home demonstration clubs for women and teaching skills like food preservation and home economics. Male extension agents educated farmers about nutrient and soil management and techniques such as terracing to reduce erosion. The Durham Cooperative Exchange also ran agricultural education programs to promote youth entrepreneurial and leadership development at Durham public schools in the city and county. Segregated schools had separate programs; Future Farmers of America served white students and New Farmers of America served Black students.160

In Black county schools, extension work was augmented by Durham’s Jeanes teachers, named for the northern Quaker philanthropist Anna Jeanes who funded the program. Beginning in 1915, these women served as tireless community organizers in the county, helping to raise money to build schools, improve public health, and foster various educational opportunities. They were officially tasked with implementing industrial education- practical skills that had the stamp of approval from white funders and the school superintendent. In the Jim Crow era, local white school administrators and the northern philanthropists that supported southern Black education held racist assumptions about what type of education Black people needed. They believed that there was a “lack of civilization” among Black people, and assumed that after leaving school, women would be doing primarily domestic work and men unskilled or semi-skilled labor. However, Durham Jeanes teacher Carrie Jordan reframed teaching subjects such as cooking, gardening, and canning food as measures of individual and community self-sufficiency “that could help Black students improve their lives- rather than simply learning to be cooks and maids for white people.”161

Across the country, and especially in the South, the extension programs were rife with racial inequities. Black extension agents received lower salaries than white agents, with far fewer opportunities for promotion and/or advancement. Black agents had inferior offices and fewer staff, demonstration materials, and supplies- despite the fact that they often had higher client caseloads than their white counterparts. These factors ensured that white farmers received greater access to information and higher levels of individual attention regarding the increasingly difficult to navigate system of government agricultural supports.162

As Durham’s urban population grew exponentially, the city established the first curb market in the state in 1911. Located in the heart of the city, the primary goal was to connect county farmers with urban consumers. Throughout the next several decades, the curb exchange attracted over 1,000 customers a month and was the highest grossing market in the state. Women usually worked the stalls, and many used the money generated for home improvements and modern appliances. The historical record is sparse on the curb market, but archival photographs indicate that the market was an outlet for both Black and white farmers, although the clientele appears overwhelmingly white. During the Depression in the 1930s, the curb market helped sustain farm families through sales of farm produce, eggs, dairy products, baked goods, canned food, flowers, and specialty items.163-164

Despite expanded agricultural support programs and market outlets, the Great Depression of the 1930s hit farmers hard. In North Carolina, farm incomes, which were already operating on narrow margins, dropped by more than a third. The national economic crisis corresponded with an ecological one, as sustained drought and soil erosion forced an exodus of farm families off the land. Moreover, commodity prices were lower than the cost of living for farm families, which contributed to an overproduction problem. At the urging of farm groups from across the county, President Franklin Roosevelt passed the Agriculture Adjustment Act in 1933. This act became commonly referred to as the Farm Bill. The first farm bill contained core legislative elements that would stay in place for decades For example, acreage reduction programs paid farmers to keep part or all of their land out of production in order to reduce excess supply, raise market prices, and rest the land. The Farm Bill also contained provisions for "nonrecourse" loans whereby grain could be used as collateral in the case of loan default. This created a government-owned surplus of grain to be sold abroad or used for early domestic hunger programs.16 In Durham, where small farmers were already struggling to survive, one of the unintended consequences of the acreage reduction program was to reinforce the decline in farming. Between the years of 1936-1942, Black farm families in Durham County decreased by a third, dropping from 515 to 344.172-174

During the Depression, widespread unemployment led to broad labor unrest across the country. Diligent organizing and protests by labor unions pressured President Franklin Roosevelt to initiate a host of reforms that made for the most extensive expansion of the social safety net ever seen in this country. These reforms, passed between 1933 and 1939, are commonly known as the New Deal. However, the benefits of these new programs were not shared equitably across race. Pressure from white southern legislators ensured that agricultural and domestic workers were excluded from new social programs. This included social security benefits and unemployment insurance (Social Security Act, 1935), new labor protection laws regarding the minimum wage (Fair Labor Standards Act, 1938), and the right to organize (National Labor Relations Act, 1935). To put this into perspective, domestic and agricultural occupations employed almost 75% of Black workers in the southern states in the 1930s. The exclusion of these workers was intentional and racially motivated. As explained by historian Ira Katznelson: “Southern legislators understood that their region's agrarian interests and racial arrangements were inextricably entwined…. By excluding these persons from New Deal legislation, it remained possible to maintain racial inequality in southern labor markets by dictating the terms and conditions of African American labor.”176-177

The federal agencies set up to support farmers also expanded greatly during the New Deal. However, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and programs such as the Federal Extension Services (FES) and the Farmers Home Administration (FmHA) each advanced practices and policies of institutional racism. A 1964 study by the Johnson administration found evidence of racial discrimination in every program of the USDA in regards to funding, employment/promotion, and decision-making. The report confirmed that while small farmers were losing out everywhere, Black farmers were segregated and "consistently outside the decision-making process." In the federal office in Washington D.C., the FmHA employed one Black professional and only one Black agent worked in the federal Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation (ASCS) office. The ASCS is a USDA agency that granted loans to farmers, purchased farm products from farmers, administered land allotment programs, and shared the cost of conservation and environmental protection measures with farmers. ASCS discrimination permeated down to the local elected county committees. These committees were dominated by white elite farmers who shorted black farmers on allotments- federal money meant to directly augment farmers’ incomes. The report also verified what many had known for decades, that the Black extension services were "distinctly inferior and provided entirely on a segregated basis," and that despite its funding and oversight role, the USDA "completely disowns responsibility for the way in which the Extension Service is operated."178-179

Discriminatory practices by the USDA continued long after the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, which legally ended racial discrimination in federal programs. In 1980, the North Carolina Black Farmers organization filed a lawsuit against the FmHA charging racial discrimination in farm aid. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission investigated the complaint and found that Black farmers received fewer loans for smaller amounts, were less likely to get deferred loan payment schedules, and more likely to have to agree to liquidation of their property if they defaulted. A subsequent USDA investigation found that Black farmers typically waited 134 days longer for loan decisions and were nearly 30% less likely to get loans approved than white applicants. Cumulatively, decades of discrimination through these programs prevented Black farmers from accessing the capital needed to sustain, adapt, and grow their farming enterprises. The result was massive transfers of both financial resources and land from Black to white farmers.180-182

Private property laws caused further troubles for Black landowners. Historically, due to issues of both trust and access, Black families were far less likely to have a will than white families. If a property owner dies without a legal will, their property passes to their direct heirs as undivided, partial shares. This form ownership transfer is called “heirs property.” Over several generations, property ownership can become unclear as dozens or even hundreds of heirs may come to own a small share.183

The consequences heirs property are often devastating to Black families. Individual heirs don’t qualify for certain Department of Agriculture loans to purchase livestock or cover the cost of planting. They are generally not eligible for disaster relief through agencies like FEMA. Further, they cannot use their land as collateral with banks, and so are denied private financing and home improvement loans. Heirs are also more vulnerable to land speculators and developers through a legal process called “partition action.” Thereby, speculators can buy off the interest of a single heir, and just one heir, no matter how small their share, can force the sale of an entire plot of land through the courts. This allows developers to exploit divisions and crises within families to force a partition action, whereby sales are usually significantly below market rate. Even today in North Carolina, hundreds of partition actions are filed every year. North Carolina is one of the few states across the country that has not adopted legislation to protect heirs from exploitation and dispossession.184

In addition to institutional channels of discrimination and exclusion, many Black farmers and land owners experienced racial intimidation in rural areas. The underlying motivation for such intimidation was often desire for their land. This forced targeted Black families to weigh the consequences of staying on under continued harassment and/or threat of violence versus opting to sell their property and pursuing a different life path.185

References

- Anderson, Jean. (2011). Durham County. Durham: Duke University Press, p. 263

- Anderson, Jean. (2011). Durham County. Durham: Duke University Press, p. 263

- Patterson, Thomas. (1920). Negro Credit Unions of North Carolina. The Southern Workman, p.180

- Open Durham. Lowes Grove Credit Union. Retrieved from https://www.opendurham.org/buildings/lowes-grove-credit-union

- Southern Oral History Program. African American Credit Unions. Retrieved from https://sohp.org/research/african-american-credit-unions/

- Patterson, Thomas. (1920). Negro Credit Unions of North Carolina. The Southern Workman, p.180

- Brown, Leslie. (2008). Upbuilding Black Durham: Gender, Class, and Black Community Development in the Jim Crow South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, p. 89-90

- Wilkerson, Isabel. (2010). The Warmth of Other Suns: the epic story of America’s Great Migration. New York, Vintage

- Mebane, Mary. (1981). Mary: an autobiography. New York: Viking Press, p. 90

- Mebane, Mary. (1981). Mary: an autobiography. New York: Viking Press, p. 20

- Daniels, Pete. (2013). Dispossession: discrimination against African American farmers in the age of civil rights. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, p. 7-10

- McGiffin, Deborah. Durham County Cooperative Extension Service Celebrates a Century of Improving Lives. NC State University/A&T State University Cooperative Extension. Retrieved from https://durham.ces.ncsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Durham-CES-histor...

- Humphries, Frederick. (1991). 1890 Land-Grant Institutions: Their Struggle for Survival and Equality. Agricultural History. 65. p. 3-11

- McGiffin, Deborah. Durham County Cooperative Extension Service Celebrates a Century of Improving Lives. NC State University/A&T State University Cooperative Extension. Retrieved from https://durham.ces.ncsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Durham-CES-histor...

- Abel, Joanne. (2009). Persistence and Sacrifice: Durham County’s African American Community and Durham’s Jeanes Teachers Build Community and Schools, 1900-1930. Master’s Thesis, Duke University, p. 23-30, 69, 87 (quote)

- Daniels, Pete. (2013). Dispossession: discrimination against African American farmers in the age of civil rights. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, p. 36-41

- McGiffin, Deborah. Durham County Cooperative Extension Service Celebrates a Century of Improving Lives. NC State University/A&T State University Cooperative Extension. Retrieved from https://durham.ces.ncsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Durham-CES-histor...

- Open Durham. Durham County Agricultural Building/Curb Market/Extension. Retrieved from http://www.opendurham.org/buildings/durham-county-agricultural-building-...

- Forsters, W.O. (1936-1940). Interview with Tom Hearst and wife. The Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Federal Writers’ Project Papers: 1936-1940. Collection #0379, Folder 391

- Open Durham. Farmers Mutual Exchange/Central Carolina Farmers Exchange. Retrieved from http://www.opendurham.org/businesses/durham-farmers-mutual-exchange-cent...

- Open Durham. Farmers Exchange Cold Storage/Freezer Lockers. Retrieved from http://www.opendurham.org/buildings/farmers-exchange-cold-storage-freeze...

- Open Durham. Farmers Exchange/Poultry Plant. Retrieved from http://www.opendurham.org/buildings/farmers-exchange-poultry-plant

- Open Durham. Farmers Exchange/Hatchery. Retrieved from http://www.opendurham.org/buildings/900-mallard-ave-farmers-exchange-hat...

- Open Durham. John O’Daniel Hoisery Mill/Farmers Exchange. Retrieved from http://www.opendurham.org/buildings/john-odaniel-hosiery-mill-farmers-ex...

- Open Durham. ‘This Is Central Carolina Farmers Exchange’ pamphlet, quoted in “Farmers Exchange/Poultry Plant. Retrieved from http://www.opendurham.org/buildings/farmers-exchange-poultry-plant

- Lehrer, Nadine. (2010). U.S. Farm Bills and Policy Reforms: ideological conflict over world trade, renewable energy, and sustainable agriculture. Amherst: Cambria Press, p 9-10

- Cooperative Extensive Service. (1936-37). Annual Narrative Report of County Home Demonstration Agent, Durham County, NC. (UA102.002), Special Collections Research Center at NC State University Libraries

- Cooperative Extensive Service. (1943). Farm and Home Improvement Contest: The Negro Farm and Home Program in Durham County, NC. Extension Circular No. 267

- Cooperative Extensive Service. (1930-1946). Extension Circulars 1930-1946 (S544.3, N8 N63 1930-1946). Special Collections Research Center at NC State University Libraries

- David Harris. (2019). Personal communication with Melissa Norton.

- Katznelson, Ira. (2013). Fear Itself: the New Deal and the origins of our time. New York: Liveright, 2013, p. 171, 241-242, 260, 268, 270-271, (quote) p. 163

- Lui, Meizhu, et al. ed. (2006). The Color of Wealth: the story behind the U.S. racial wealth divide. New York: New Press, p. 92-93

- Daniels, Pete. (2013). Dispossession: discrimination against African American farmers in the age of civil rights. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, p. 27-30;

- Meizgym Lui et al ed. (2006). The Color of Wealth: the story behind the U.S. racial wealth divide. New York: New Press, p. 105

- Daniels, Pete. (1986). Breaking the Land: The Transformation of Cotton, Tobacco, and Rice Cultures since 1880. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, p. 164.

- Mittal, Anurandha. (2000). The Last Plantation. Institute for Food and Development Policy. 6(1)

- Lui, Meizhu, et al ed., (2006). The Color of Wealth: the story behind the U.S. racial wealth divide. New York: New Press, p. 106

- Barclay, Delores and Lewan, Todd. (2001). Torn from the Land (part III). Associated Press. Retrieved from https://theauthenticvoice.org/teachersguide/teachersguide_tornfromtheland/

- Presser, Lizzie. (2019). Their Family Bought Land One Generation After Slavery. The Reels Brothers Spent Eight Years in Jail Refusing to Leave it. ProPublica. Retrieved from https://features.propublica.org/black-land-loss/heirs-property-rights-wh...

- Barclay, Delores and Lewan, Todd. (2001). Torn from the Land (parts I and II). Associated Press.

“In the spring and summer after work, my mother would plant in her garden: tomatoes, string beans, okra, and she'd sow a turnip patch. Then every day after work, she'd go over to the garden on the hill to see how it was doing. On Saturday's she'd get her buckets if it was time for us to go berry-picking. And on hot summer evenings, if the peaches man had been around, she'd can them after work because they wouldn't keep until Saturday, the day she did most of her canning. This was her routine- fixed, without change, unvarying. And she accepted it. She more than accepted it, she embraced it; it gave meaning to her life, it was what she had been put here on this earth to do. It was not to be questioned.” “Berry-picking was a ritual, a part of the rhythm of summer life. I went to bed, excited...We didn't know whose berries they were; nobody had heard about the idea of private property. Besides, the berries grew wild- free for everybody...The grown people picked up high and the children picked low...The berries were long and cylindrical; and the blacker why were the sweeter they were. Some that had started drying up were almost as sweet as candy. We children ate them on the spot, putting purple-stained fingers into our mouths, creating purple-stained tongues while the grown people wiped sweat and dodged bumblebees.” - Mary Mebane, on growing up in a Black farming community in Northern Durham County (ref 155-156)

“Electricity is here and I’m saving every penny I can. I hope to get a Frigidaire and washing machine. And I will. My husband lets me have what I make at the curb market in Durham. We pay a very little rent for our market space, about 10 cents a yard, I believe. I take in butter, eggs, cottage cheese, cream, and anything I have time to bake. Some of the women have made several hundred dollars off of their cakes during a season. Others bring in flowers; seems like they sell better than vegetables. I forgot to say, we also take in canned vegetables and fruit. I canned over 300 quarts for the family last summer on our old place. But now we’ve moved up here with all this fruit, I’ll have a chance to put up a heap.” - Mrs. Tom Hearst, a white farmwife from Durham County (ref 165)

"A Poultry Plant to process and market large amounts of poultry was one of the first operations started by the Exchange to give local farmers a source of income other than tobacco. When the Department began operating in 1931, there was very little poultry being grown in this section - not much more than what it took to feed the farmers. However, farmers were quick to see what mass production and wholesale marketing of poultry could do for them. Today, Central Carolina is known for its production of broilers, which provides the second largest farm income in the State. – “This is Central Carolina Farmers Exchange,” promotional pamphlet from 1956 (ref 170)

“We’s got some mean neighbors around here. They hates us ’cause we own and won’t sell. They want to buy it for nothing. They don’t like for colored people to own land. So they got a white lady, Mrs. Jones, on the next farm to say that I attacked her. I hope to be struck down by Jesus Christ if I said or did anything she could kick on... Mary can tell you I’ve never been too friendly with any white woman. “That’s right,” Mary agreed; It’s all prejudice against a colored family that’s trying to catch up with the whites. They hated my father because he owned land and my mother because she taught school and now they are trying to run us off. But we are going to stay on.” - Willie Roberts, Black Durham County mechanic and farmer, and Mary Roberts, interviewed in the 1930s. (ref 186)