Durham Food History

While Durham County was still largely farmland, the first decades of the 1900s saw incredible urban growth as the city’s population swelled from less than 7,000 in 1900 to more than 60,000 in 1940. The rapidly expanding city came of age during the Jim Crow era (1896-1964), a time defined by a racial caste system shaped by both laws and social customs. The term Jim Crow comes from a popularized caricature of Black people performed by white actors in blackface in the 1800s. In North Carolina, a series of laws were adopted that dictated racial segregation of nearly all sites of life, including schools, transportation, and public facilitates. Interracial marriage was outlawed. In addition to legal segregation, complex rituals developed that guided all social interactions between white and Black people, from forms of address to movements on sidewalks. As a body of law, Jim Crow institutionalized economic, educational, and social disadvantages for African Americans and Native Peoples living in the South. As a body of ritual, Jim Crow reinforced a physical and psychological racial hierarchy that placed whites at the top and all other racial groups in positions of deference and subordination.93-95

The city’s growth was driven overwhelmingly by rural migration, primarily from nearby counties in North Carolina. Pushed primarily by economic hardship, rural migrants came seeking new opportunities in the city. Each year, thousands of farmers traded in their ties to the land for a steady paycheck working in Durham’s rapidly growing tobacco and textile industries. The textile industry was only open to white workers, but the tobacco industry provided jobs for both Black and white urban migrants- although Black workers were relegated to the lowest paying, most backbreaking jobs within the factories. In the city, people who had grown up farming and living off the land had to adjust to a new way of life characterized by wage labor, a cash economy, and dense urban living.97

For Durham’s rural migrants, the shift to urban living fundamentally changed how people ate and their relationship to food. Before home refrigeration was widespread in the 1940s, most households bought groceries or had perishable groceries such as meat and milk delivered daily. There were extensive neighborhood-based grocers, and much of the food such as milk, eggs, meat, and produce was still sourced locally and regionally. Since many households were first generation urbanites, they maintained knowledge about food production and keeping animals learned on the farm.98

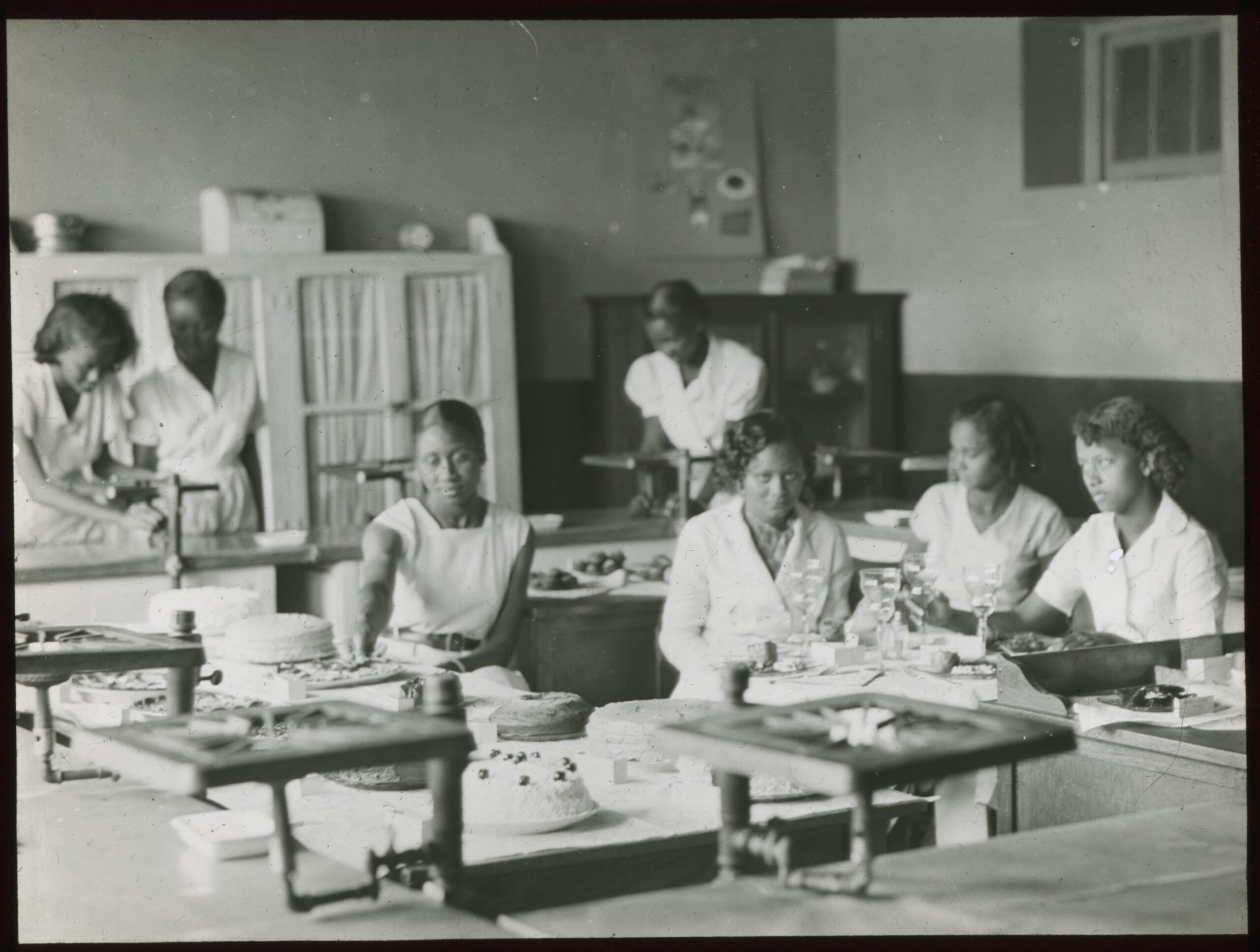

Women’s’ unpaid labor in the home was the backbone of urban foodways- a term that refers to cultural, social, and economic practices relating to the production and consumption of food. Such labor was often in addition to paid work outside of the home. Black women were more likely to experience this ‘double burden,’ as many worked in the tobacco factories or as domestic laborers for low wages. White families, except for the very poor, and the small Black middle class hired domestic workers to do much of the food shopping, preparation, and cooking. Both Black and white city and county schools taught girls practical education about gardening, cooking, and food preservation in home economics classes.99-100

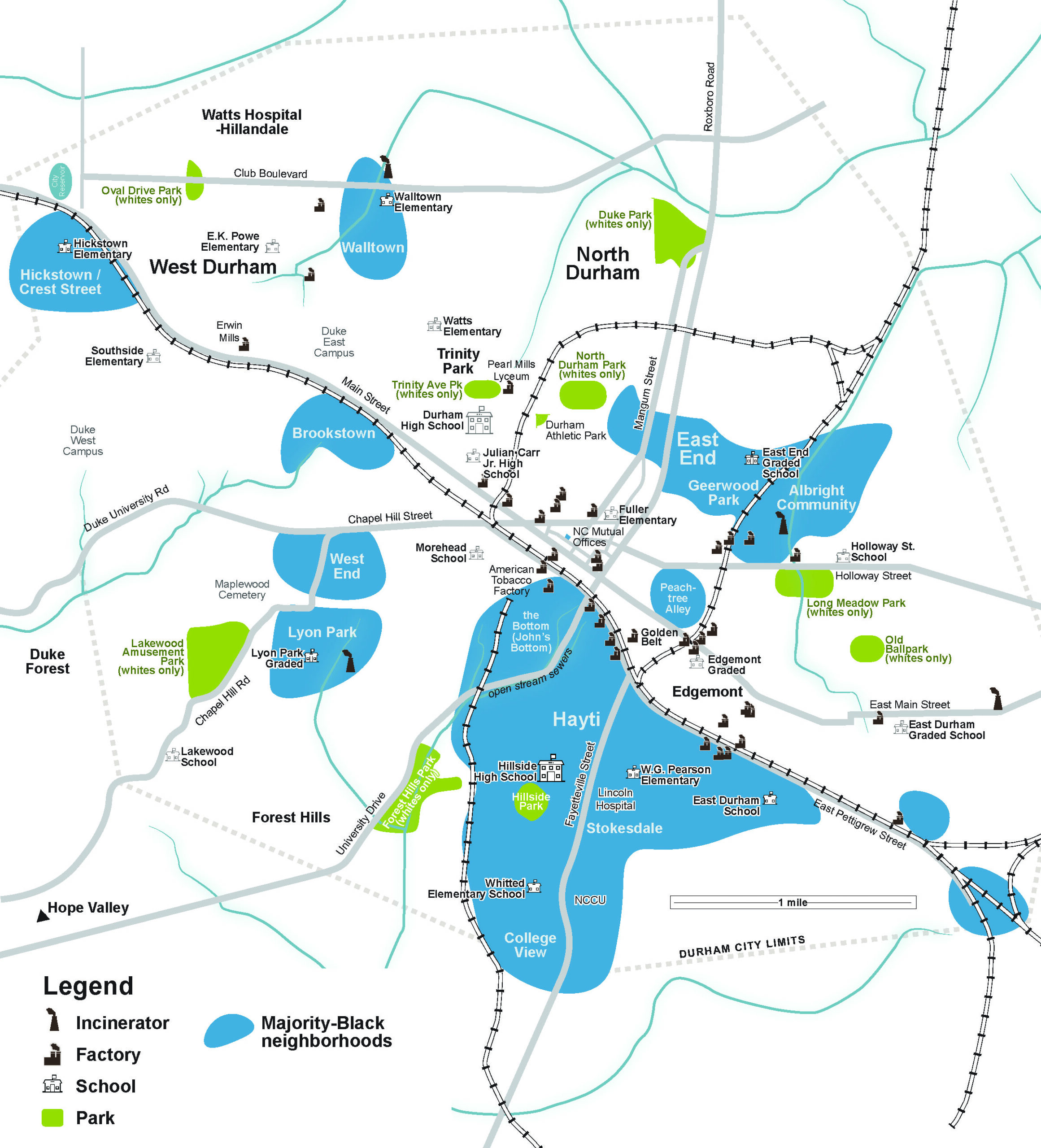

In the city of Durham, neighborhoods segregated by both race and class sprouted up around the factories that dotted the urban landscape. Durham’s white working class neighborhoods of East Durham, Edgemont, and West Durham were located near textile mills on the east and west flanks of the city. There were six Black neighborhoods. Hayti, the largest neighborhood, was located just south of downtown and actually contained a number of smaller geographic communities. The other Black neighborhoods were the West End/ Lyon Park, Brookstown, Hickstown, Walltown, and the East End. Before the introduction of water, sewer, and drainage systems, the prime urban real estate was located in the high and dry areas. The less desirable land, where most of the Black neighborhoods were located, fell in the ‘bottoms,’ which were low-laying areas easily prone to flooding. This housing pattern is known as ‘segregation by elevation.’ Initially, prestigious white homes were located in the heart of the city, in neighborhoods such as Trinity Park and Morehead Hill. With the advent of the streetcar system and more widespread automobile ownership, new high-status white neighborhoods formed the first ring of suburbs, including Forest Hills, Hope Valley, Watts Hospital Hillandale, and Duke Forest.101

In the early 1900s, textile mill owners in East Durham, Edgemont, and West Durham built subsidized homes in close proximity to the factories for white workers called mill villages. Each mill village contained its own churches, schools, recreation centers, and stores. Though wages were low, mill village families supported each other through hard times, and treated their neighbors like family. Many textile workers had grown up on farms and continued to maintain gardens and keep livestock like chickens, pigs, or even cows, in their yards. It was common to preserve extra garden produce and meats by canning for the winter. Canning became popular in the first few decades of the 1900s, and increased greatly during both of the World Wars when food shortages resulted in the rationing of canned food. Government programs urged people to rely on produce grown in their own gardens- dubbed “Victory gardens”- and to share resources with neighbors. In the West Durham mill village around Erwin Mill there was a company store where nearly all the workers would put in their grocery orders. The company store eventually became replaced by neighborhood grocers in the 1930s.102-106

For many white textile workers, especially during the Great Depression in the 1930s, it was extremely hard to make ends meet. The textile industry was hit hard by the recession and its workers experienced economic hardship and emotional stress. Most families survived on basic staples of fatback (a cheap cut of meat), flour, beans, and homegrown produce. But in periods of unemployment or underemployment, hunger was never far off. For acute hard times, food relief programs run by the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (created in 1933) followed by the Works Progress Administration (created in 1935) distributed surplus food through a community relief store. While these supplies staved off hunger, both Black and white recipients complained that these foods did not always match with local food customs and practices. The Durham community also came together to support those in need. When the Durham Hosiery Mill closed in 1935 and 450 people were put out of work, churches stepped in and raised nearly $100,000 (in 2020 dollars) for food and clothing for impacted families.109-110

Looking to improve their lives through organizing and collective action, white union membership swelled and there were a series of textile strikes in the 1930s and 1940s. As one labor union leader described Erwin Mills in West Durham, “His mill villages are better than most other companies…but he preaches baths, swimming pools and that kind of thing, and then won’t pay a wage that is anything near even a living wage.” Neighborhood grocers often had deep relationships with the workers and would distribute food on credit to workers during strikes.112-113

“Yea, it [the company store] was a complete store. They’d have very few wives work in the mills (around the 1930s). They would have a man who went out in the morning and they called it ‘taking orders.’ He’d go to all the houses and the woman of the house would tell him what she wanted and he’d bring it back in time to be cooked and served up for what they called dinner, which is of course lunch. And he’d go do the same thing in the afternoon and have it back in time for a good supper." – Zeb Stone, white business owner from West Durham (ref 107)

“Our seedy run-down school told us that if we had any place at all in the scheme of things it was a separate place, marked off, proscribed and unwanted by the white people. We were bottled up and labeled and set aside- sent to the Jim Crow car, the back of the bus, the side door of the theater, the side window of a restaurant. We can to know that whatever we had was always inferior. We came to understand that no matter how neat and clean, how law abiding, submissive, and polite, how studious in school, how churchgoing and moral, how scrupulous in paying our bills and takes we were, it made no essential difference in our place.” – Pauli Murray, reflecting on growing up as a Black child in Jim Crow Durham (ref 96)

“The young Jacksons and Mrs. Jackson occupy the two bedrooms and Clarence sleeps on a cot in the room which is used as a combination of kitchen and dining room. This 3-purpose room has in it no space for storing the canned fruits and vegetables which the elder Mrs. Jackson prepared during the summer. Consequently, the jars have been arranged in neat rows across the corner near the fireplace in the living room and just opposite the upright piano. There are 200 jars of beans, tomatoes, corn, peaches, pickles, and preserves. All the vegetables were gathered from the Jackson garden just back of the house…” - The Jackson Family, white textile workers in West Durham, 1938 (ref 108)

“I go around to the place that the WPA distributes commodities, and this last time they give me four packs of powdered skim milk, five pounds of country butter, three pounds of navy beans, 24 pounds of flour. That was graham flour and it makes awful bread. I’ve tried every way I could think of to cook it, and I ain’t been able to do anything with it yet. That stuff just ain’t fitten for a dog to eat, but I have to use everything I can get…One of the boys gets up early every morning and goes out and picks berries for breakfast. They, with butter, do make that flour eat a lot better. He wants to pick some for preserves, but we can hardly get sugar for our needs right now. But there is something about us that keeps us hoping that in some way the future will take care of itself.” - unemployed white textile worker in East Durham (ref 108)

In the first half of the twentieth century, Black people streamed into the city from rural areas searching as historian Leslie Brown described “for work and each other.” Together, Black Durhamites engaged in a collective process of “Upbuilding,” a term coined by the eminent sociologist and historian W.E.B. Du Bois to describe the social and economic development of Black communities after slavery. Six Black neighborhoods formed in the city, and along with them came Black churches, schools, and businesses. Each of these neighborhoods sustained close relationships, bolstered by shared workplaces and places of worship. The largest among them was the Hayti, named after the first independent Black republic in the western hemisphere. Pettigrew and Fayetteville Streets in Hayti became the epicenter of Black businesses in town.”114

During this time of Upbuilding, patronizing Black businesses amounted to investing in the whole community, and community leaders preached how each dollar spent would flow in a wheel of progress throughout Black Durham. In this vein of racial solidarity, a wave of Black-owned businesses rose up, most notably the city’s flagship Black institution the North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company. As a result, from the early 1900s through the 1950s nearly everything needed in life could be purchased from a Black business in Hayti, an area that functioned in many ways as a city within a city.115

Recognizing that access to capital on reasonable terms was essential for the growth of businesses and new housing development, Black business leaders founded Mechanics & Farmers Bank in 1909. The bank soon became an important source of financing for Black entrepreneurs, homeowners, and farmers. It was also patronized by white people who thought it the best way to keep their financial affairs confidential. One of only a few Black-owned banks in the country to survive the Great Depression, it is credited with saving more than 500 African American farms and residences from foreclosure. The bank's policy stated its intent to provide "no large loans . . . to a few profiteers, but rather conservative sums to needy farmers and laborers."117-118

Neighborhood grocers owned by Black people (and by Jewish and white proprietors in some limited cases) such as Katz Grocery, Superior Market, the Progressive Stores, Smith’s Grocery, and JL Page and Sons served Black neighborhoods. In the early days, neighborhood grocers would do deliveries and some would take their wares directly to the people in what were essentially mobile grocery stands. As Benjamin Page, whose family owned JL Page and Sons recounts: “My father would go out on the streets, as what we called “street peddlers, and take vegetables and things and sell them off his wagon… and my mother would stay and take care of the store.” Farmers of all races from the county would come into the urban areas and select street corners to sell fresh produce, creating pop-up farm stands throughout the city. One account recalls a “meat man” who would drive in from the county and sell live chickens and cuts of pork and chitterling throughout Hayti. Even though yards were often small, many Black people maintained gardens and kept chickens, until the local government banned livestock in the city limits in the 1940s. A 1930 survey indicated that nearly 75% of Black middle class homes and approximately 50% of working class homes had gardens.120-124

Throughout the first half of the 1900s, Black people consistently comprised roughly a third of Durham’s population, and nearly a quarter of the City restaurants were designated as "colored” in the City Directory of 1945. These included 21 restaurants operated by and for Black people in Hayti, and five others in Walltown, the East End, and the West End/Lyon Park. Black-owned restaurants ran the gamut from soul food to seafood, from diners to banquet halls, and provided community gathering spaces both for everyday life and for special occasions.19

The Hayti area, which contained Lincoln Hospital, the North Carolina College for Negroes (now North Carolina Central University), and many other Black civic institutions, became an essential stop for Black activists, entertainers, and academics travelling the country. These visitors connected Black Durham to broader cultural and political movements, often sharing news and stories over food. Azona Allen, proprietor of Hayti restaurant the Green Candle, recalled how “singers like Ike and Tina Turner would come spend weeks at the Biltmore Hotel and I used to feed them.”20

“We didn’t have to go across the tracks to get anything done. We had our own savings and loans bank, our own insurance company, our own furniture store, our own tailors, barbershops, grocery stores –the whole nine yards.” - Henry M. “Mickey” Michaux, longtime Durham state representative on growing up in Hayti (ref 116)

“Everybody used Mechanics & Farmers. Even in elementary school, they taught us to bank at Mechanics & Farmers. I don’t know what happened to all those accounts, but everyone who went to my school had an account at Mechanics & Farmers.” - David Harris, on growing up in a Black farm family in Northern Durham County (ref 119)

Although Durham was known across the country for being a center of the Black middle class, the vast majority of Durham’s Black residents were working class who labored for low wages. To justify low wages, white employers employed racist arguments that Black workers were accustomed to living on less, were inefficient, and that equal pay would result in racial tensions that would disrupt the workplace. In the hot and dusty tobacco factories, both women and men worked 9-hour shifts, with a half-hour lunch break. Workers would leave early in the morning after a simple breakfast- typically along the lines of biscuits, molasses, and coffee. In the early years, there were no cafeteria facilities provided for Black workers, and so people "ate everywhere, in cars, on the street, anywhere you could get a seat." Eventually, through pressure from the local Black labor union, there was a cafeteria onsite at American Tobacco and Ligget Myers where many Black workers ate together- albeit, separate from white workers. For these hard-working people, the long-held tradition of Sunday meals and outings after church allowed time for rest, connection, and communion.21

From 1900-1930, Black women outnumbered men by as much as 15% in the City of Durham, as women left their families in rural areas, either seasonally or permanently, to find ways to increase family incomes. As W.E.B. Du Bois observed at the time, “the Negroes are put in a peculiarly difficult position, because the wage of the male breadwinner is below the standard, while the openings for colored women in certain lines of domestic work, and now in industries, are many. Thus while toil holds the father and the brother in the country and town at low wages, the sisters and mothers are called to the city.” Some of the jobs available to Black women were seasonal, particularly in the tobacco “green season” where Black women were in high demand in the tobacco factory’s stemmeries (work considered too difficult and grimy for white women). In addition to tobacco factory work, many women became domestic workers, who cooked, cleaned, laundered, and did childcare for white families. Their meager wages were sometimes supplemented by food and hand me down clothes, which helped make ends meet. Nonetheless, families became incredibly resourceful on how to “stretch” a meal over the course of several days when resources ran thin.135-137

For Durham’s Black working class, who occupied the bottom rung of the economic ladder, poverty and food insecurity increased acutely during the Great Depression. This was apparent in the rise of pellagra, a disease stemming from nutrient deficiency and poor quality food. While the disease impacted poor people across race, Black Durhamites were more than six times more likely to experience pellagra than whites in 1930. After tuberculosis, it was the leading cause of death in the city. Public health nurses would try and counsel urban migrants on the value of green vegetables and fresh milk, but would often hear that it was economics, not lack of knowledge that was the source of poor eating habits. As one Black patient remarked, “we would like to do everything you say but we just haven’t got the money.”139-140

Food relief came from federal programs like the Works Progress Administration and charities such as the Red Cross, but it was never enough to address the sustained needs of people facing chronic unemployment. As aid efforts from federal, state, and local government shifted from direct aid towards employment and training programs, race and gender dictated what opportunities were available to Black Durhamites. For example, WPA funds financed a job training program focused on domestic services for Black women on relief rolls. Employment discrimination during the Great Depression increased resolve in the Black community to fight for better economic opportunities. In 1936, Louis Alston, editor of Durham’s Black newspaper The Carolina Times, helped organize a boycott of grocers that served Black people, but would not hire them. Picketers carried signs that read “Don’t Buy Where We Can’t Work.” Quickly feeling the economic pinch, both A&P and Kroger grocery stores soon began hiring Black workers.141-142

Through good times and bad, mutual aid in Black Durham held communities together and helped keep people fed. In systems of mutual aid, communities take on the responsibility for caring for one another, rather than forcing individuals to fend for themselves. Mutual aid is not the same as charity, whereby a centralized organization is the intermediate of aid and giving occurs in one direction. Rather, mutual aid fosters symbiotic relationships where people offer material goods or assistance to one another. In Durham, Black women’s church groups and clubs were at the forefront of mutual aid efforts. Groups such as Jack & Jill, Daughters of Dorcas, The Links, and various missionary circles “made and collected food, clothes, and fuel as expressions of morality and faith.” In oral histories, people would commonly reflect that even though they were poor, they didn’t feel poor, because their basic needs were met, and they noted the ways that communities would share and take care.143-144

“On Saturday we'd be getting ready for going to church, cooking and figuring what we were going to wear. We'd shine up those shoes and get everything in place and be ready to dress up and go to church, because we knew we were going to have a good time that Sunday. We would get out and go to places, maybe an ice cream place, a drugstore. We would go and get us an ice cream soda and get with the group on Sunday, the girls and the boys, and we would have a good time. Then we had another place called the Donut Shop on Pettigrew Street, and we'd get a chance to go in there at a wedding or something, or maybe some Sunday afternoon we'd go down and sit at the grill.” - Margaret Turner, Black tobacco worker (ref 133)

“Dinner on the church grounds was a very special occasion. Every family brought a basket, with enough to share with others. During the latter part of the service, the ladies would quietly "tip" out of the auditorium to go to their cars, where they had left the baskets. The men had constructed makeshift tables under the trees, which were covered with sparkling white table cloths. Then the great baskets were opened: huge stacks of fried chicken, dark and crispy brown, nestling next to hills of potato salad, yellow and with green bits of pickles; beef roast already sliced and in its own gravy; giant pink ham slices with a brown-sugar crust; bowls of string beans with a ham slice in them; English peas and freshly sliced country tomatoes; pound cake; sweet-potato pie; blackberry pie; corn bread, biscuits, and light bread. When the service was over and dinner was served, men and women took plates and moved from dish to dish, taking a piece of chicken from this sister and another specialty from the next. The women encouraged them by saying, ‘Try a piece of mine,’ And another would say, ‘Have a piece of this.’ By the time they had moved down the length of the table, their plates were piled three or four layers deep- and still there was something left that they had not had a chance to try. They piled their plates and stood around on the grounds eating and exchanging news of the crops, the weather, the war, President Roosevelt, and what the prospects were for the coming year. I marvel that people who would now be considered below the poverty level on any statistical chart still had enough sense of self of human worth to enjoy sharing what they had with others. The meal was the tie that binds.” - Mary Mebane, on the importance of Sunday meals at the church she attended in Wildwood, a Black farming community in North Durham County (ref 134)

“... people would share with each other.... Used to be if you found out a family was hungry, didn't have nothing to eat, they'd scrap up a little bit here, a little bit there and they would give it to them. You don't find that now. People used to have what they call in your community, your church, what they call a ‘pounding.’ It didn't have to be a pound but that's what they called it. You'd take a little bit of flour over here, a couple of cups of flour, somebody else would take a couple of cups and put it in a bag or a few beans or a little piece of fatback meat. They call it salt pork now, they don't call it fatback no more. And they would carry it to the church and would distribute to these families.” - Horace Mims, Black American Tobacco worker (ref 145)

“ … Trying to live and pay my bills with that $57 a month, we would eat like rice and maybe I’d take fried fatback and take the flour and make gravy, and we’d have rice and gravy and fatback like today and tomorrow. I’d probably cook a cabbage and then Wednesday I would have the rice, cabbage, whatever was left over we ate, that’s the way I fed the children. And I used cloth bags, flour bags and rice bags, to make their clothes, to make the slips and the dresses and things out of. At that time, the bags had little designs on them and I thought they were right pretty, and so I made them on my hand, and I thought the children were right cute.” - Ann Atwater, on life as a single mom and Black domestic worker in the 1950s and 60s. (ref 138)

“Looking back, I can see that we had a real sense of security. We had so many people watching out for us, no matter what we did. You were known, your family was known, the families relied on one another. Looking back it was wonderful… No matter if I didn’t have a lot of money, I could still bring my kids up and not give up.” – Emma Johnson, on growing up in Hayti (ref 146)

References

- United States Census data for Durham, 1900 and 1940

- Woodward, C. Vann. (2001). The Strange Career of Jim Crow. Oxford: Oxford Community Press, (commemorative ed.), p. 7

- Davis, Ronald. Racial Etiquette: The Racial Customs and Rules of Racial Behavior in Jim Crow America. Retrieved https://files.nc.gov/dncr-moh/jim%20crow%20etiquette.pdf

- Murray, Pauli. (1956). Proud Shoes: the story of an American family. Boston: Beacon Press, (1999 ed.), p. 270

- Janiewski, Dolores. (1985). Sisterhood Denied: race, gender, and class in a new south community. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, p. 55-57

- History.com. History of Household Wonders: history of the refrigerator. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20080326092256/http://www.history.com/exhibi...

- Brown, Leslie. (2008). UpBuilding Black Durham: Gender, Class, and Black Community Development in the Jim Crow South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, p. 44

- Westin, Richard. (1960). A History of the Durham School System 1882-1933. Master’s Thesis, Duke University, 1960, p.68-71.

- Phillips, Coy. (1947). City Pattern in Durham, NC. Economic Geography, 23(4)

- Leloudis, James, Korstad, Robert, Murphy, Mary, Jones, Lu Ann, and Daly, Christopher. (1987). Like A Family: the making of a Southern cotton mill world. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press

- Rand, Lanier. (1977). Interview with Bessie Taylor Buchanan. Southern Oral History Program Collection, Series H: Piedmont Industrialization (04007H)

- Hayden-Smith, Rose. (2015). Sowing the Seeds of Victory. Jefferson, NC: McFarland

- Gowdy-Wygant, Cecelia. (2013). Cultivating victory: the women’s land army and the victory garden movement. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press

- Anderson, Jean. (2011). Durham County. Durham: Duke University Press, p. 253, 326

- Franck, Richard C. (1975). An Oral History of West Durham, North Carolina. Zeb Stone Interview, done for the Durham Bicentennial Committee

- Moore, Ida. (1936-1940). Interview with the Jackson Family. Federal Writers’ Project Papers: 1936-1940. Collection #0379, Folder 1027. The Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

- Franck, Richard C. (1975). An Oral History of West Durham, North Carolina. done by for the Durham Bicentennial Committee

- Anderson, Jean. (2011.) Durham County. Durham: Duke University Press, 293-296

- Moore, Ida. (1946-1940). East Durham Mill Village. The Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Federal Writers’ Project Papers: 1936-1940. Collection #0379, Folder 678

- Franck, Richard C. (1975). An Oral History of West Durham, North Carolina. done for the Durham Bicentennial Committee

- Fletcher, Joseph and Miller, Spencer. (1930). The Church and Industry. New York: Longmans Green, 231

- Brown, Leslie. (2008). UpBuilding Black Durham: Gender, Class, and Black Community Development in the Jim Crow South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, p. 9, 30-31

- Weare, Walter. (1973). Black business in the New South: a social history of the North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, p. 95-99

- Interview with Henry M. “Mickey” Michaux, interviewed by Eliza Meredith 2015, for Duke thesis: The Long History of Policing Black Durham

- Weare, Walter. (1973). Black business in the New South: a social history of the North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, p. 120

- Mechanics and Farmers Bank. NCPEDIA. Retrieved from https://www.ncpedia.org/mechanics-and-farmers-bank

- David Harris, personal communication with Melissa Norton, 2019

- John Hope Franklin Research Center, Duke University Libraries. (1995). Interview with Benjamin Page (btvnc03028), interviewed by Mausiki S. Scales and Valeries Bellamy, Durham (N.C.). Behind the Veil: Documenting African-American Life in the Jim Crow South Digital Collection

- Brown, Leslie. (2008). UpBuilding Black Durham: Gender, Class, and Black Community Development in the Jim Crow South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, p. 222

- Mebane, Mary. (1981). Mary: an autobiography. New York: Viking Press, p.119

- Johnson, Emma (pseudonym) and Partner, Simon. (2013). Bull City Survivor: standing up to a hard life in a southern city. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, p. 19

- Brinton, Hugh. (1930). The Negro in Durham: a study of adjustment to town life. Doctoral Thesis, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, p. 219-220

- Hill Directory Company, Hill’s Durham (Durham County, N.C.) City Directory [1945-46], Digital NC. Retrieved from https://lib.digitalnc.org/record/25168?ln=en

- Covington, Artelia. (2001). Group honors Hayti legend. The Durham Herald Sun

- Brown, Leslie. (2008). UpBuilding Black Durham: Gender, Class, and Black Community Development in the Jim Crow South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, p. 44, 294-295

- Du Bois, W.E.B. (1912). The Upbuilding of Black Durham, The Success of the Negroes and Their Value to a Tolerant and Helpful Southern City. World’s Work, vol. 23

- Washington, Booker T. (1911). Durham, North Carolina: A City of Negro Enterprises. New York, NY: Independent

- Frazier, E. Franklin. (1925). Durham: Capital of the Black Middle Class. Indianapolis, Indiana: Bobbs-Merrill

- Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. (1979). Interview with Margaret Holmes Turner by Beverly Jones. Southern Oral History Program Collection #4007. Southern Historical Collection Interview # H-0233

- John Hope Franklin Research Center, Duke University Libraries. (1994). Interview with Horace Mimms (btvnc03025), interviewed by Gregory Hunter, Durham (N.C.). Behind the Veil: Documenting African-American Life in the Jim Crow South Digital Collection

- Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. (1979). Interview with Margaret Holmes Turner by Beverly Jones. Southern Oral History Program Collection #4007. Southern Historical Collection Interview # H-0233

- Mebane, Mary. (1981). Mary: an autobiography. New York: Viking Press, p. 82-83

- Janiewski, Dolores. (1985). Sisterhood Denied: race, gender, and class in a new south community. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, p. 55-57, 62;

- Brown, Leslie. (2008). UpBuilding Black Durham: Gender, Class, and Black Community Development in the Jim Crow South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, p. 45, 83-84, 88-89

- Du Bois, WEB. (1920). The Damnation of Women. Darkwater: Voices from Within the Veil. New York: Washington Square Press (2004 edition)

- Ann Atwater. (2010). Personal communication with Robert Korstad. Retrieved from https://www.schoolforconversion.org/extended-interview-with-ann-atwater

- Brinton, Hugh. (1930). The Negro in Durham: A Study of Adjustment to Town Life. (Unknown Binding), p. 269, 288-289

- Anderson, Jean. (2011). Durham County. Durham: Duke University Press, p. 213

- Anderson, Jean. (2011). Durham County. Durham: Duke University Press, p. 294-296

- Gershenhorn, Jerry. (2018). Louis Alston and the Carolina Times: a life in the long black freedom struggle. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, p. 26

- McMenamin, Leslie. (2020). What is Mutual Aid and How Can It Help With Coronavirus. Vice. Retrieved from https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/y3mkjv/what-is-mutual-aid-and-how-can...

- Brown, Leslie. (2008). UpBuilding Black Durham: Gender, Class, and Black Community Development in the Jim Crow South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, p. 33