Durham Food History

In the wake of urban renewal and the building of NC Highway 147, a continued cycle of disinvestment afflicted the central city from the 1970s through the 1990s. Many people who could leave, did. The result was a pattern of both white flight and substantial Black middle-class flight to the quickly expanding suburbs. In their wake, community institutions and businesses such as banks and grocery stores also disappeared. These closures left significant parts of the city underbanked and lacking access to food. At the same time, a huge economic shift was taking place in Durham, whereby the unionized, well-paying factory jobs that had employed Durham’s working class for generations began to leave town for good. In the 1980s and early 1990s, Erwin Mill (J.P. Stevens), American Tobacco, Golden Belt, and Liggett & Myers and all shuttered their doors, leaving millions of square feet of empty factory space and thousands in need of new jobs. In a few short years, 1,000 jobs were lost at American Tobacco, 650 at Erwin Mill, and 1,500 at Ligget & Myers. Hourly wages at these factories (in 2020 dollars) ranged from $15 an hour at Erwin Mill to $33 an hour at American Tobacco. Upon hearing of American Tobacco’s plans to close their Durham plant in 1986, machinist Melvin Alston remarked “It’s just like dropping a bomb in Durham and clearing everyone out.” These transitions of homes, institutions, and workplaces disrupted much of the infrastructure of community life.236-238

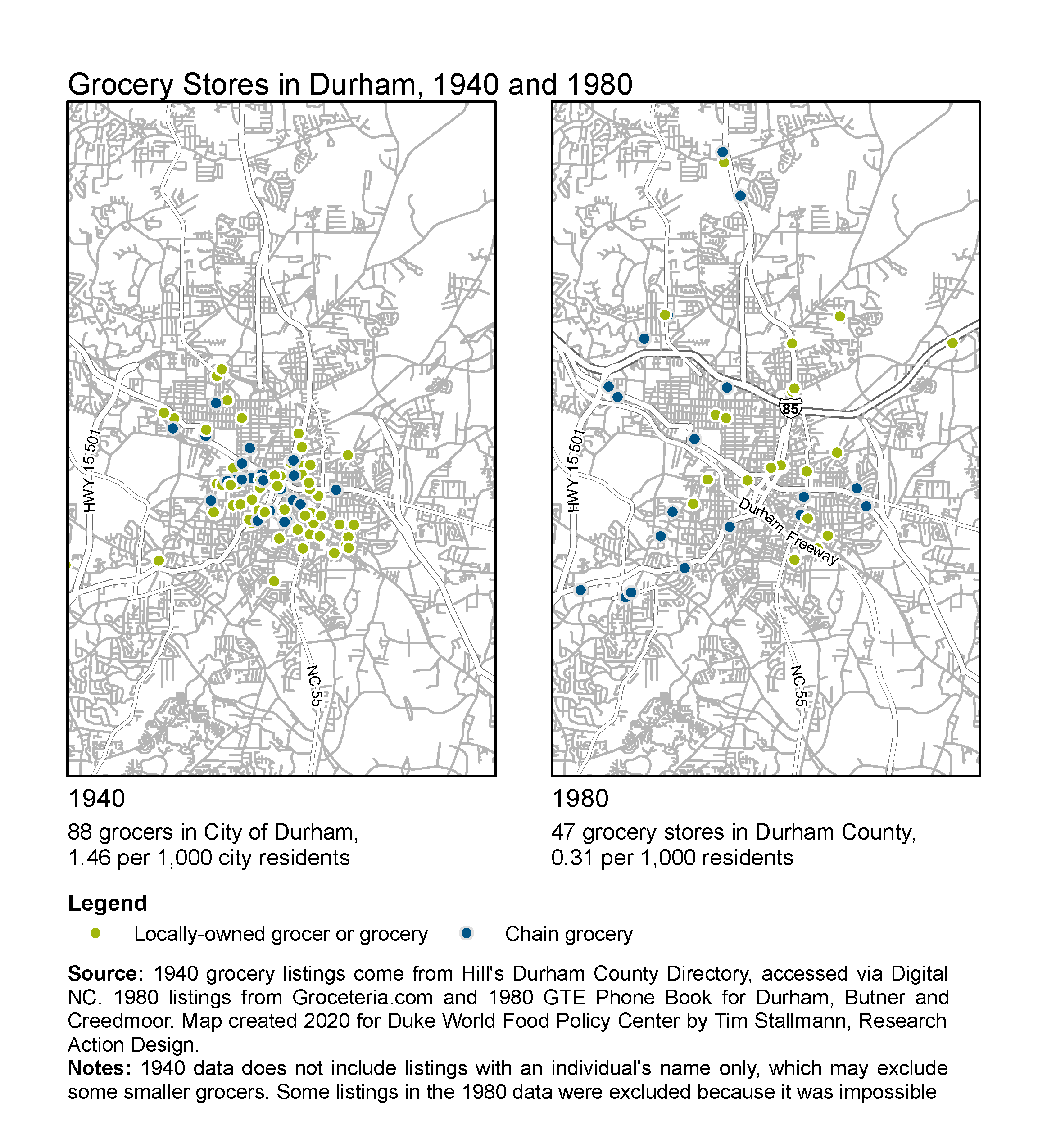

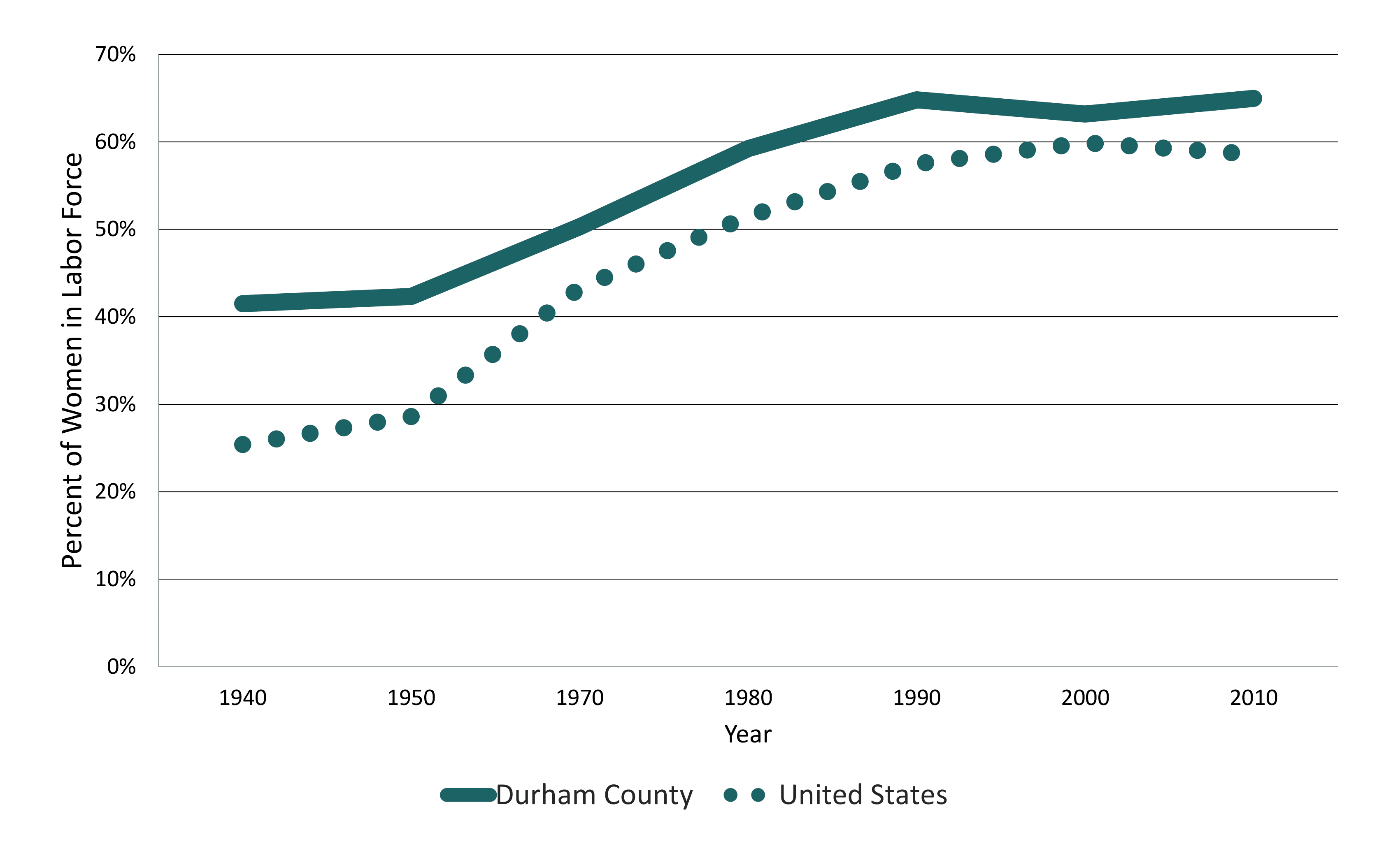

Uneven investment across the growing urbanized landscape along with increasing industrialization and corporate control of the food system greatly impacted how people accessed their food, the types of food people ate, and public health. Across Durham, and across the United States, neighborhood grocers gave way to progressively larger, consolidated corporate grocery stores with big parking lots for shopper’s vehicles. The majority of these stores were located in the new suburban growth areas. Home refrigeration, on the rise since the end of WWII, was now nearly universal, allowing households to extend the time periods between shopping. Home microwaves, almost nonexistent at the beginning of the 1970s, were in more than a quarter of homes by1980 and kept growing in popularity. Changes in how food was stored and cooked were accompanied by increasing numbers of women working outside the home and a rise in single parent households. This transition encouraged a demand for convenience foods, food from restaurants, prepared meals at grocery stores, or microwaved from the freezer.239-241

In the wake of urban renewal and the building of NC Highway 147, a continued cycle of disinvestment afflicted the central city from the 1970s through the 1990s. Many people who could leave, did. The result was a pattern of both white flight and substantial Black middle-class flight to the quickly expanding suburbs. In their wake, community institutions and businesses such as banks and grocery stores also disappeared. These closures left significant parts of the city underbanked and lacking access to food. At the same time, a huge economic shift was taking place in Durham, whereby the unionized, well-paying factory jobs that had employed Durham’s working class for generations began to leave town for good. In the 1980s and early 1990s, Erwin Mill (J.P. Stevens), American Tobacco, Golden Belt, and Liggett & Myers and all shuttered their doors, leaving millions of square feet of empty factory space and thousands in need of new jobs. In a few short years, 1,000 jobs were lost at American Tobacco, 650 at Erwin Mill, and 1,500 at Ligget & Myers. Hourly wages at these factories (in 2020 dollars) ranged from $15 an hour at Erwin Mill to $33 an hour at American Tobacco. Upon hearing of American Tobacco’s plans to close their Durham plant in 1986, machinist Melvin Alston remarked “It’s just like dropping a bomb in Durham and clearing everyone out.” These transitions of homes, institutions, and workplaces disrupted much of the infrastructure of community life.236-238

Uneven investment across the growing urbanized landscape along with increasing industrialization and corporate control of the food system greatly impacted how people accessed their food, the types of food people ate, and public health. Across Durham, and across the United States, neighborhood grocers gave way to progressively larger, consolidated corporate grocery stores with big parking lots for shopper’s vehicles. The majority of these stores were located in the new suburban growth areas. Home refrigeration, on the rise since the end of WWII, was now nearly universal, allowing households to extend the time periods between shopping. Home microwaves, almost nonexistent at the beginning of the 1970s, were in more than a quarter of homes by1980 and kept growing in popularity. Changes in how food was stored and cooked were accompanied by increasing numbers of women working outside the home and a rise in single parent households. This transition encouraged a demand for convenience foods, food from restaurants, prepared meals at grocery stores, or microwaved from the freezer.239-241

Many of the new convenience foods were processed, meaning mechanical or chemical operations were performed to change or preserve it. Processed foods are typically found in a box or a bag in the inner aisles of the grocery store and at fast food outlets and convenience stores. These foods, never before known in the millions of years of human evolution, became a central part of the American diet, with some estimates claiming that they now make up as much as 70% of our calories. Processed foods were seen as a beneficial way to keep raw material costs low and extend the shelf life of food. However, they are often lower in nutritional value than unprocessed foods and are high in sugar, fat and empty calories. Such foods may contain unhealthy food additives. Consuming significant amounts of processed foods has been linked to increased risk of health problems such as heart disease, diabetes, high blood pressure, elevated cholesterol, cancer and depression. Processed foods are also cheaper, more accessible, and more heavily marketed to food insecure households than whole, unprocessed foods. These factors have been linked to the racial and economic disparities in diet-related illnesses.242-246

Since the 1960s Durham County has become increasingly less agricultural, and now is one of the least agricultural counties in the state. Today, only a small fraction of our food is produced locally. Instead, like most U.S. cities, Durham’s food comes from all around the world. Industrial agriculture is now the dominant food production system in the United States. It is characterized by large-scale monoculture, heavy use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides, and meat and milk production in confined animal feeding operations (CAFOs). Under this model, farms have come to resemble factories more than nature, with “inputs” such as pesticides, feed, fertilizer, and fuel, and “outputs” such as soybeans, pork, etc. Yet, the goals to increase yields and decrease costs of production through economies of scale have been incredibly successful, as world food production nearly doubled from 1961-1996, with only a 1.1 fold increase in cultivated lands.247-248

In nearly every way, industrial farming is far removed from the interdependence and biodiversity of natural ecosystems as possible, and is a vast departure from historically diversified farms. Each year, billions of pounds of pesticides are applied to crops. Farmworkers and communities adjacent to industrial farming operations are often exposed to high levels of these toxic chemicals, with both short-term and chronic health impacts. These chemicals then enter the food system and are consumed by people and animals- although science is still catching up on how this affects our bodies. In the industrial agriculture model, a few crops reign supreme. In particular, some limited varieties of corn and soybeans that overwhelmingly end up as animal feed, biofuels, and processed food ingredients.

Widespread monoculture reduces soil fertility, requires costly applications of chemical fertilizers, and intensive irrigation. In industrial meat, milk, and egg operations, animals receive massive doses of hormones to promote fast growth and antibiotics to ward off the infections and diseases that thrive in the unsanitary and crowded conditions of CAFOs. High concentrations of confined animals also produce substantial amounts of bio-waste. While historically, animal waste has been a useful fertilizer for crops, factory farms produce far more than can be assimilated by nearby land, and so this waste ends up in large treatment areas that cause water and air pollution and emit high levels of greenhouse gasses. Cumulatively, industrialized agriculture is having global environmental repercussions, including massive deforestation, habitat loss for a wide variety of species, and a shortage of ecosystem services, such as pollination, that a more diverse landscape offers. Scientists have estimated that the industrial food system is responsible for somewhere between one-fifth to one-half of the human actions that are causing climate change. This impact is driven by dependence on fossil fuels to produce pesticides and fertilizers, to process food, and to transport it across the globe, as well by the methane released from massive livestock operations.249-252

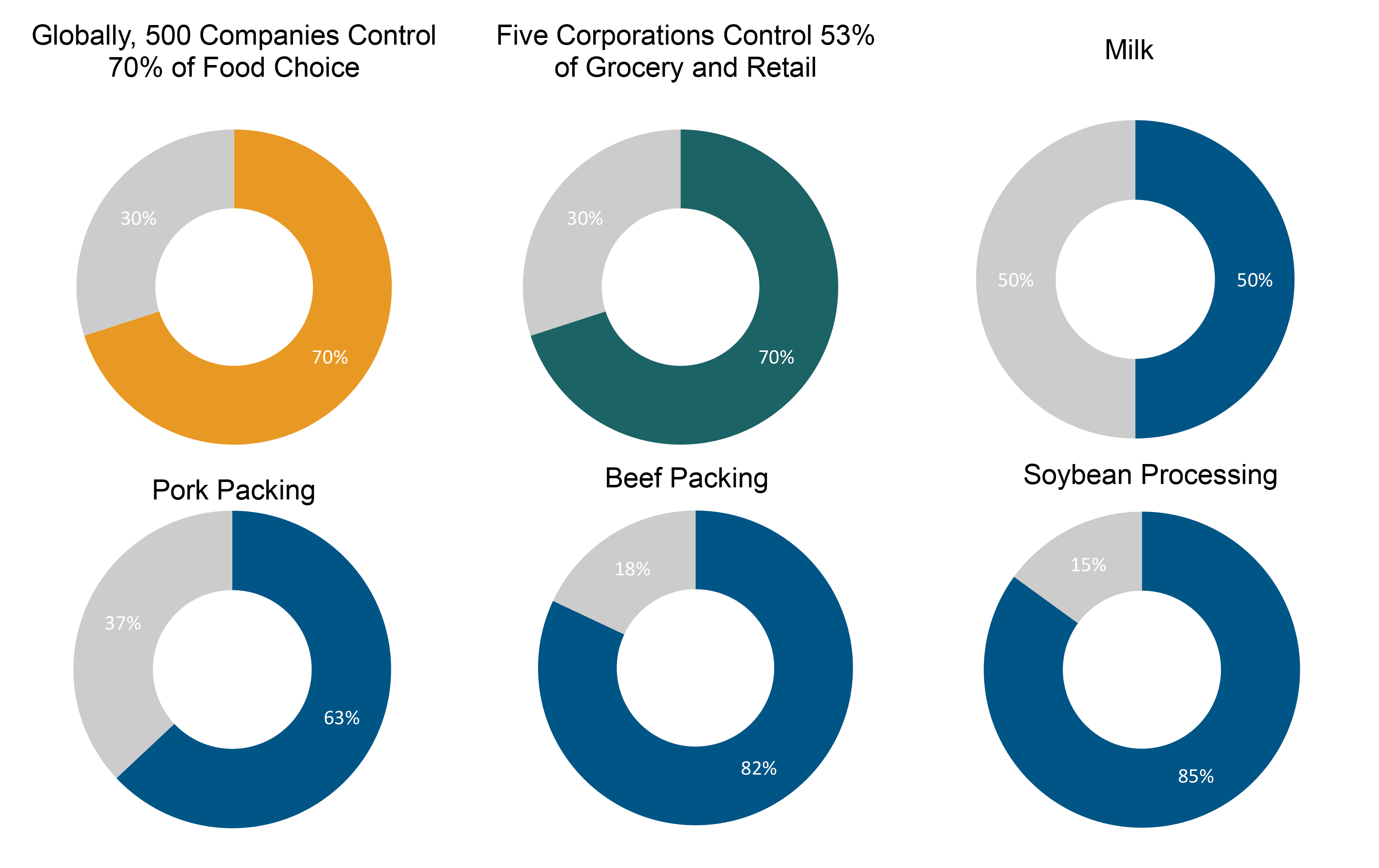

Shifting policy priorities in the Farm Bill in the last quarter of the 20th century steadily increased corporate control and consolidation within the food system. Corporate control refers to control of political and economic systems by corporations in order to influence trade regulations, tax rates, and wealth distribution, among other measures, and to produce favorable environments for further corporate growth. Corporate consolidation refers to a concentration of corporate ownership within each part of the food system, including production, processing, and distribution. Since its beginnings in 1933, the Farm Bill has been the keystone agricultural policy in the US. It is an omnibus bill enacted approximately every five years and is shaped by a variety of for-profit and nonprofit interest groups and corporations by way of lobbying, campaign donations, and other such efforts. Leading up to a new farm bill, a broad range of interests line up to advocate and form alliances in order to best meet the needs of their constituents. These include groups focused on farm policy, commodity and industry interests, the environment, rural development, hunger-relief, public health, and sustainable agriculture.253-254

After several decades of few major changes, the 1973 Farm Bill opened up a new era of drastic deregulation. It was influenced by an economic recession, high fuel prices, and failed harvests abroad which all led to a worldwide grain shortage for the first time in many years. Wanting to increase agricultural production, President Nixon’s Secretary of Agriculture, Earl Butz, called for farmers to plant “fencerow to fencerow” and “get big or get out!” These directives were reinforced by a Farm Bill that moved away from the long-held policy of farmer loans and incentives to periodically rest their land towards direct farmer subsidies. But after the recession passed and the world grain supply went back up, the intense overproduction of commodity crops, subsidized by the federal government, primarily benefited corporate buyers while farmers continued to lose their lands and income to larger consolidated operations.255-256

Beyond favorable buying conditions, corporations have increasingly come to control the food system including the manufacturing and distribution of seed, fertilizers, pesticides and machinery, as well as food processing, distribution, marketing, and retail. This control puts wealth, influence, and decision-making concerning the entire food system in the hands of very few. Moreover, starting in the 1980s, legal rulings extended the notion of private property beyond land and water to include the fundamental components of life itself by allowing seed genetics to be patented.257

Like many Americans, Durham residents have become increasingly disconnected from the land and our food production, both physically and culturally. Without a clear guide map of how to eat, food corporations use marketing and media to shape ideas and perceptions about what we should eat and why. Although public health guidance has changed very little over the past 100 years, the public health and nutrition world’s fractional budget cannot create enough counter-marketing to change narratives created by food corporations. Not all foods are marketed equally. In the early 2000s, more than 70% of food advertising was for convenience foods, candy and snacks, alcoholic beverages, soft drinks, and desserts- whereas only a tiny fraction went toward promoting fruits, vegetables, grains, or beans. In this highly competitive food environment, no person is too young to become a consumer, and the food and beverage industry has developed savvy ways of influencing children’s product preferences, requests, and diet. There is a strong association between increases in advertising for non-nutritious foods and rates of childhood obesity and diabetes. Companies often target Black and Hispanic consumers with marketing for their least nutritious products, contributing to diet-related health disparities affecting communities of color.258-261

Since the early 1980s, the political environment has seen a decline in the robust mid-century social movements led by labor unions and people of color that yielded the expansion of the social safety net and major civil rights legislation. These social movements and progressive political reforms resulted in a period of decreased income and wealth inequality between the New Deal in the 1930s through the War on Poverty of the 1960s to the late 1970s. In its place has been rise of a political ideology known as “neoliberalism” that emphasizes the value of free market competition and the belief that free markets are the most efficient way to allocate resources. Neoliberalism prizes low taxes, privatization, deregulation, and free trade, and the dismantling of government entitlements and social programs in favor of market-based solutions. The past 40 years of neoliberal policies has led to historic levels of inequality across the globe.262-264

Upon taking office in 1981, President Ronald Reagan championed this neoliberal ideology by simultaneously cutting taxes for the wealthy and spending for the poor, slashing welfare benefits, funding for public housing, grants for mass transit, and food assistance. As a result, food insecurity spiked during his tenure and economic inequality widened to levels not seen since the end of the 1960s. To justify these austerity policies, Reagan invoked stereotypes and caricatures of the poor as undeserving welfare queens, freeloaders, and con artists whose food stamps and welfare benefits were a drain on the system and were costing undo taxpayer expenditures. Unlike the previous decades where the media’s stories of poverty had frequently included poor whites in Appalachia and other rural communities, the images promoted by Reagan focused on Black people living in urban poverty. In Durham in the 1980s, reductions in federal poverty and hunger programs were felt acutely. Despite the number of poor people remaining relatively constant between 1981-1987 the number of people receiving welfare benefits dropped by 20% and foodstamps by 25% due to tightening eligibility requirements. As a result, local health care providers reported a significant uptick in patients with malnutrition related illnesses such as anemia, low-birth weight, and protein deficiency.265-268

With a reduction in programs striking directly at the root causes poverty, downstream charity programs developed to help alleviate its symptoms. Having charity programs address the structural issues of racial and economic inequality were encouraged by President Reagan, who said “if every church and synagogue in the United States would average adopting 10 poor families beneath the poverty level… we could eliminate all government welfare in this country.” This focus on volunteerism and charity continued under President George H.W. Bush in his “thousand points of light” framing where he claimed “What government can do is limited, but the potential of the American people knows no limits.” Nonprofits, a tiny sliver of the US economy before 1970, mushroomed into a major sector of the economy. A number grew up in Durham in the 70s and 80s to address the issues of hunger and food insecurity. Meals on Wheels started in 1975, the Food Bank of Central and Eastern North Carolina in 1980, Urban Ministries of Durham in 1983, and the Interfaith Food Shuttle in 1989. Across the country, more than 80% of pantries and soup kitchens currently operating came into existence between 1980 and 2001. In Durham and elsewhere, many of these food charities focused on reducing food waste, which was increasingly recognized as an absurd reality in the face of chronic food insecurity for so many. A 1974 national survey estimated that approximately 20% of the food manufactured in the U.S. for human consumption was being thrown out. In 2020 that percentage is as high as 30-40%.269-274

In the midst of major reductions to the social safety net, Reagan sensationalized the use of drugs and the crime associated with it to implement a “war on drugs.” When signing the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, Reagan declared “The American people want their government to get tough and to go on the offensive.” Despite the evidence that drug usage was highest among white people, this “war” disproportionately targeted low-income communities of color- and especially Black men. In 1988, under Reagan’s Anti-Drug Act, the Durham Housing Authority received federal funding for the city to pay off-duty police officers to patrol high-crime areas. This funding was paired with a Durham program called Crime Area Target Teams (CATT) that increased the number of police officers stationed in public housing developments. These types of concentrated policing efforts continued into the 2000s with the Bull’s Eye Initiative, which intensified policing in two square miles consisting of predominantly poor communities of color east and south of downtown. While the introduction of drugs like crack cocaine waged a serious toll on neighborhoods in the central city, so did the decision to respond disproportionately with policing rather than public health interventions.278-281

Hyper-policing, drug criminalization, and longer sentencing caused incarceration rates to rise steadily. As a result, there were deep financial, emotional, and health impacts on families and communities swept up in its path. On the front end of criminalization, individuals and families can go into debt from bail bonds and court fines. While in jail or prison, many lose jobs and income and endure stressful periods of separation from their friends and family. In Durham County jails, incarcerated people consistently complain about the quality of food, with a combination of soy-textured protein and potatoes served at nearly every meal described as "pig slop." Others have spoken out about the injustice of working in the kitchen or laundry without receiving any compensation- although huge food service corporations like Aramark are netting record profits. Upon returning home, justice-involved persons face barriers to employment and securing adequate housing and are often excluded from government programs and supportive services. North Carolina is one of the states where people with felony drug convictions are still eligible for food stamps. However, they may have a temporary disqualification period when released from prison- often the time when benefits are needed most acutely- and may have to join a treatment program or be drug tested. One of the consequences of mass incarceration is extremely high levels of food insecurity, which impacts 90% of people returning from prisons and jails.283-284

While food charities have expanded and have deeply dedicated staff and volunteers, the emergency food system is insufficient to meet the ongoing needs of hungry and food insecure people in Durham and elsewhere. Moreover, funders encourage food charities to measure success in ways that do not actually address the root causes of food insecurity or its nutritional impacts. Outputs such as the weight of food pounds distributed or the number of people served are heralded as signs of progress versus indicators centered on health, nutrition, and well-being.286-288

Notwithstanding government rollbacks, it is the public sector that plays the most critical role in hunger relief and food security. Government nutrition and anti-hunger programs such as Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), WIC (Women Infants and Children), and school breakfast and lunch programs have been the largest recipient of Farm Bill allocations for the past 50 years. Although SNAP is technically a supplemental support program, many recipient households rely on SNAP benefits for most or all of their monthly grocery budget. Even then, the money often runs short, and benefits do not necessarily ensure access to healthier foods, which are more expensive. Originally allocated as booklets of food stamps, the stigma of using SNAP lessened in 2008 when benefits shifted to electronic debit cards (EBT-Electronic Benefits Transfer). These types of payments are also more widely accepted. The impacts of SNAP and other programs like WIC and free and reduced lunch for school children are significant- lifting many families out of abject poverty and acute hunger.289-290

In the ongoing national debates over entitlements, eligibility requirements for food assistance play out in each Farm Bill legislation. As benefit amounts and eligibility requirements change frequently, it makes it difficult for participants to cope with food insecurity. The SNAP program’s budget was dramatically cut by $26 billion over six years in the 1996 Farm Bill. These reductions to SNAP eligibility took place at the same time as President Bill Clinton’s Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA)- more commonly known as “Welfare to Work.” Together, these policies changed the landscape of food assistance by limiting eligibility and length of benefits for able-bodied adults without dependents who are not working at least 20 hours a week or participating in a work program. Currently, Durham is one of only 13 out of North Carolina’s 100 counties that have such programs. Nevertheless, these policies changes had local impacts. In Durham County, SNAP benefit recipients decreased by 14% between 1997 and 2001, despite a nearly 2% increase in the poverty rate in the 1990s.291-294

During the Great Recession of 2007-2009, job losses, wage reductions, and a foreclosure crisis all greatly increased the number of people facing food insecurity. This led to a dramatic uptick in SNAP usage. However, in the 2014 Farm Bill, Congress reduced benefits for 48 million people, including more than 21 million children. This erosion of the SNAP program has continued under the Trump administration, which approved an administrative rule change in 2020 that will make it harder for states to waive employment requirements. In what is now a common refrain, Trump’s Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue said in a press release, “We need everyone who can work, to work,” despite the growing body of evidence that work requirements do not make it any easier for people to find work, do not align with the current work economy, and make it harder for people to feed themselves. As the COVID crisis unfolds and food insecurity spreads across the country at unprecedented rates, expanding the SNAP program is currently in an intense partisan debate in Congress.295-297

The 2008 Farm Bill introduced the concept of a food desert, which defined it as “a census tract with a substantial share of residents who live in low-income areas that have low levels of access to a grocery store or healthy, affordable retail outlets.” However, the imagery of a desert as a natural ecosystem where few things grow, obscures the fact that these areas are a direct result of a long history of intentional divestment through discriminatory policies and institutional decisions. As such, “food apartheid” is a more accurate description of the reality that some people have food abundance and others food scarcity depending on their race, class, and zip code. Food apartheid is more than a geographic phenomenon. It involves a broad intersection of structural factors such as: transportation/transit access, financial resources, availability of healthy food options in close geographic proximity, strength of community networks, language barriers/access, knowledge about assistance programs, and prevalence of easier food options.298

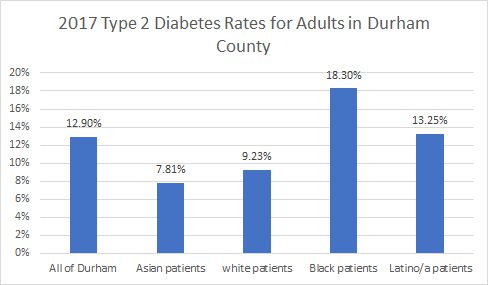

The cumulative effects of living under food apartheid have profound impacts on health, well-being, and life expectancy of people of color and poor people. For example, diet-related illnesses such as diabetes that barely existed 100 years ago are now among our biggest public health concerns. People of color and poor people have disproportionately high incidents of diabetes. In 2017, Black patients were 80% more likely than white patients to have diabetes in Durham. In a 2016 survey in the Piedmont region, 16% of respondents with household incomes less than $15,000 reported having diabetes, compared to 6% of respondents with household incomes of more than $75,000.299-300

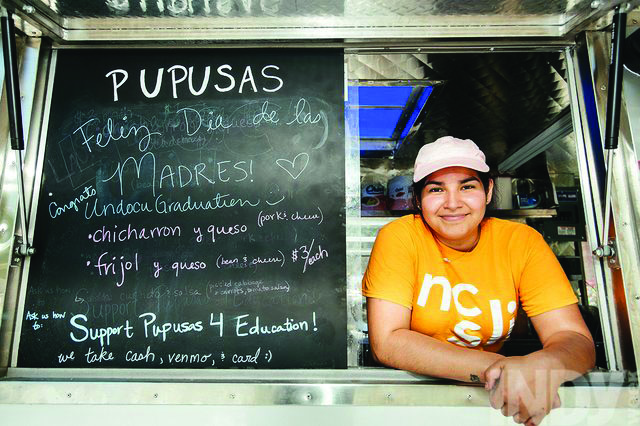

U.S. neoliberal trade policy has also impacted Durham. In the decade following the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), over 1.3 million farmers in Mexico alone were driven out of business and left the land. When NAFTA removed trade tariffs, companies exported corn and other grains to Mexico below cost, and rural Mexican farmers could not compete. This is one reason for the wave of migration from Central America to places like North Carolina- where Latinos came to fill jobs in the agriculture and construction industries. As the initial trickle of migration picked up into a steady flow, the Latino population in Durham grew from just over 2,000 people in 1990 to nearly 40,000 in 2014, including one out of three Durham Public School students. Like the migrants of previous generations, most came looking for safety, opportunity, and a better future for their children. 302-303

The first wave of Latinos in Durham came in the early 1990s, and clustered in houses and apartment buildings in existing low-income neighborhoods. With very few community resources Latinos went about learning how to navigate a host of new institutions and systems. In this period of adjustment to a new place and way of life, food was a source of identity and continuity among the changes. Culturally familiar foods were initially hard to come by, but as the numbers of Latinos grew, that eventually became a business opportunity.

The Latino Credit Union opened in 2000, at a time when three quarters of Latinos did not bank at all. The institution provided Spanish language staff and became a banking and home loan resource. Over the past twenty years, Latino owned and operated restaurants, grocery stores, and services have spread across Durham, providing the Latino population with culturally resonant food, community gathering spaces, jobs and opportunities. These food businesses, and others opened by migrants from elsewhere around the world, have dramatically impacted the ways Durhamites eat.

Beyond poverty and economic resources, a number of unique factors impact food security in the Latino community. These include lack of knowledge about food assistance programs, limited program eligibility due to immigration status, and fear that participation in programs will trigger Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) notification, detention, or deportation. Immigration status-related fears arose for many with George W. Bush’s 2008 Secure Communities policy, which was expanded by President Barak Obama in 2011. Secure Communities is a proactive deportation program that established a partnership among federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies. While meant to target immigrants accused of crimes, many others were swept into the immigration enforcement system through the program. Fears have been further exacerbated by Donald Trump’s inflammatory anti-immigration rhetoric. Since 2017, eligible immigrant group participation for SNAP has declined nationwide, with only about half of those eligible participating. Language barriers are another obstacle eligible immigrants face. While Durham Social Service offices are required to provide some kind of language services, this is not always enforced.307-309

Although Durham produces very little of its own food, North Carolina is one of the most agricultural states in the country, and one does not have to travel far to come across major farming operations for foods such as sweet potatoes, poultry, pork, corn, soybeans, and peanuts. Even though the overall number of farmworkers in North Carolina has decreased over the past twenty years, the number of migrant farmworkers has nearly doubled. Today, 94% of migrant farmworkers in North Carolina are native Spanish speakers, and so the struggles for food justice and immigration justice are closely tied. There is a long history of exploiting immigrant labor to maintain low prices and high profits in the food system. One of the first significant pieces of legislation was the Bracero program of 1942, whereby contract laborers from Mexico were allowed into the country to fill the labor gap opened up by WWII soldiers serving abroad and by Black people who entered the Great Migration to northern and western states from 1910 to 1970, or who otherwise left rural areas. Later on, the H2A guest worker program of 1986 allowed agricultural employers to hire seasonal foreign workers. These workers come on special visas and are contracted to a particular farm, but do not have the same labor protections as US citizens. Even in case of Latino citizens, the exclusion of labor protections for agricultural workers established in the Jim Crow era are still in effect, connecting Black and Latino workers historically in a river of struggle. Without Latino workers, the US food system would collapse. Yet the labor of these workers are consistently exploited by corporations and largely invisible to the broader public.310-312

References

- Fergus, Devin. (2009). Liberalism, Black Power and the Making of American Politics 1965-1980. Athens: University of Georgia Press, p. 81

- X, Malcolm. (1964). Message to the Grassroots. Speech, Northern Negro Grass Roots Leadership Conference, Detroit, Michigan

- Flagg, Michael. (1986). Leaf firm to leave Durham. The News and Observer (Raleigh), p. 1A

- Joyce, Katherine. (1987). Plant’s closing leaves void in Durham. The News and Observer (Raleigh), p. 1F

- Marks, Ed. (1986). Workers at mill are told details of plant shutdown. The News and Observer (Raleigh), p. 1C

- Cavolt, Jesse, et al. The Microwave: impact on American Society. The History of Tech. Retrieved from http://historyoftech.mcclurken.org/microwave/the-impact/

- Bader, Emily. (2014). The unbelievable rise of single motherhood in America over the last 50 years. Washington Post Wonkblog. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2014/12/18/the-unbelievable-...

- Warner, Melanie. (2014). Pandora’s Lunchbox: how processed food took over the American meal. New York City: Scribner, p. 205-206

- Warner, Melanie. (2014). Pandora’s Lunchbox: how processed food took over the American meal. New York City: Scribner, p. 5, 65, 137

- Avoid these foods for a healthier heart. Harvard Health Publishing Heartbeat. Retrieved from https://www.health.harvard.edu/healthbeat/avoid-these-foods-for-a-health...

- Srour, Bernard, et al. (2020). Ultraprocessed Food Consumption and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes Among Participants of the NutriNet-Santé Prospective Cohort. JAMA Intern Med. 180. p. 283-291

- Fiolet, Thibault, et al. (2018). Consumption of ultra-processed foods and cancer risk: results from NutriNet-Santé prospective cohort. The BMJ, 360, doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k322

- Ye, Li, et al. (2017). Dietary patterns and depression risk: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research. 253, p. 373-382

- North Carolina Annual Statistics Bulletin. (2018). USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service

- Tilman, David et al. (2002). Agricultural sustainability and intensive production practices. Nature, p. 418

- Union of Concerned Scientists. (2019). Farmworkers at Risk: the growing dangers of pesticides and heat. Retrieved from https://www.ucsusa.org/sites/default/files/2019-12/farmworkers-at-risk-r...

- Altieri, Miguel. (2009). The Ecological Impacts of Large-Scale Agrofuel Monoculture Production Systems in the Americas. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 29(3) p. 236-244

- Burkholder, JoAnn et al. (2007). The Impacts of Waste from Concentrated Feeding Operations on Water Quality. Environmental Health Perspectives, 115(2) p. 308–312

- Aubrey, Allison and Hersher, Rebecca. (2019). To Slow Global Warming, U.N Warns Agriculture Must Change. NPR. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2019/08/08/748416223/to-slow-global...

- Elsheikh, Elsadig and Ayazi, Hossein. (2016). The US Farm Bill: corporate power and structural racialization in the United States food system. Haas Institute Research and Policy Report, University of California Berkeley, p. 6

- Lehrere, Nadine. (2010). U.S. Farm Bills and Policy Reforms: Ideological Conflicts over World Trade, Renewable Energy, and Sustainable Agriculture. Amhurst, New York: Cambria Press. p. 18-23

- Lehrere, Nadine. (2010). U.S. Farm Bills and Policy Reforms: Ideological Conflicts over World Trade, Renewable Energy, and Sustainable Agriculture. Amhurst, New York: Cambria Press. p. 11

- Philpott, Tom. (2008). A reflection on the lasting legacy of 1970s USDA Secretary Earl Butz. The Grist. Retrieved from https://grist.org/article/the-butz-stops-here/

- Elsheikh, Elsadig and Ayazi, Hossein, (2016). The US Farm Bill: corporate power and structural racialization in the United States food system. Haas Institute Research and Policy Report, University of California Berkeley, p. 33-34

- Nestle, Marion. (2002). Food Politics: how the food industry influences nutrition and health. Los Angeles and Berkeley: University of California Press, p. 22

- Frazao E, ed. (1999). America’s Eating Habits: changes and consequences. Washington, DC: USDA, p. 173-180

- The Impact of Food Advertising on Childhood Obesity. American Psychological Association. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/topics/kids-media/food

- Harris, Jennifer, et al. (2019). Increasing disparities in unhealthy food advertising targeted to Hispanic and Black Youth. Rudd Report. Retrieved from http://uconnruddcenter.org/files/Pdfs/TargetedMarketingReport2019.pdf

- Guthman, Julie. (2008). Neoliberalism and the Making of Food Politics in California, Geoforum 39(3) p. 1171

- Harvey, David. (2005). A Brief History of Neoliberalism. New York: Oxford Press, p. 5-38

- Stone, Chad et al. (2020). A Guide to Statistics on Historical Trends in Income Inequality. Center for Budget and Policy Priorities. Retrieved from https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/a-guide-to-statisti...

- Stephen Mihm. (2013). Reagan’s Revolution Devolves Into a Food Stamp Skirmis. BloombergView, Retrieved from http:// www.bloombergview.com/articles/2013-09-23/reagan-s-revolutiondevolves-in...

- DeNavas-Walt, Bernadette D. Proctor, and Jessica C. Smith. (2011). Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States. U.S. Census Bureau, p. 50

- Lybarger, Jeremy. (2019). The Price You Pay: on the life and times of the woman known as the welfare queen. The Nation. Retrieved from https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/josh-levin-the-queen-book-review/

- The Durham Hunger Task Force and Duke University Prespectives on Hunger Class. (1987). Poverty and Hunger in the Midst of Prosperity: a growing crisis in Durham. P. 7, 10

- O’Brien, Doug, et al. (2004). The Charitable Food Assistance System: The Sector’s Role in Ending Hunger in America. The UPS Foundation and the Congressional Hunger Center 2004 Hunger Forum Discussion paper

- Olek, Joan. (1983). Spiritual groups take new aim at poor’s material needs. News and Observer (Raleigh). p. 1A

- Points of Light History. Retrieved from https://www.pointsoflight.org/history/

- Research on the chronology of Durham-based food non-profits done by Taylor Woolen, 2019

- Spencer, Marilyn. (1981). Food bank has a better idea for surplus goods. News and Observer (Raleigh). p. 8

- USDA. Food Waste Facts. Retrieved from https://www.usda.gov/foodwaste/faqs

- Olek, Joan. (1983). Spiritual groups take new aim at poor’s material needs. News and Observer (Raleigh). p. 6A

- Ronald Reagan Presidential Library and Museum. (1986). Remarks on signing the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986. Retrieved from https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/research/speeches/102786c

- Szalavitz, Maia. (2011). Study: Whites More Likely to Abuse Drugs Than Blacks. Time Magazine

- Northeast Central Durham Partners Against Crime Advisory Report. (1994). An Initiative to Create More Secure Living Environment With a Special Focus on Northeast Central Durham, p. 6

- Crime Victims ‘Fighting Back.’ (1983). Durham Morning Herald (Durham).

- Few Gardens Police Station Stirs Debate. (1983). Durham Herald Sun (Durham)

- Chalmers, Steven. Message to the community from Police Chief Steven Chalmers on Operation Bull’s Eye. Durhamnc.gov. Retrieved from https://durhamnc.gov/DocumentCenter/View/2155/Operation-Bulls-Eye-PDF

- Walk, Trey. (2019). It Takes a Village: a history of public housing in Durham, NC. 1950-2005. Honors Thesis, Duke University

- Bouloubasis, Victoria. (2016). Durham Jail Classifies Inmate Workers as Volunteers. Indy Week. Retrieved from https://indyweek.com/news/durham/durham-jail-classifies-inmate-kitchen-w...

- Gamblin, Marlysa. (2018). Mass Incarceration: a major cause of hunger. Bread for the World Briefing Paper, no. 35. Retrieved from https://www.bread.org/sites/default/files/downloads/briefing-paper-mass-...

- Chuckwumeka Manning. (2020). Personal communication with Melissa Norton.

- A Place at the Table, documentary directed by Silverbush, Lori and Jacobson, Kristi. 2012: Magnolia Pictures

- Crites, Betsy. (2015). Shame is not on poor but on state lawmakers. Herald Sun (Durham)

- Fischer, Andy. (2017). Big Hunger: the unholy alliance between corporate America and anti-hunger groups. Boston: MIT Press

- Wheaton, Laura and Tran, Victoria. (2018). The Anti-Poverty Effects of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. Urban Institute

- Gassman-Pines, Anna and Schenk-Fontain, Anika. (2019). Daily Food Insufficiency and Worry among Economically Disadvantaged Families with Young Children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 81(5) p. 1269-1284

- Elsheikh, Elsadig and Ayazi, Hossein. (2016). The US Farm Bill: corporate power and structural racialization in the United States food system. Haas Institute Research and Policy Report. University of California Berkeley, p. 41

- US Census. Census poverty data, 1960-2000. Retrieved from http://census.gov/hhes/www/poverty/data/census/1960/index.html

- US Census. Census poverty data, 1960-2000. Retrieved from http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.x...

- Durham County SNAP data from Federal Reserve Economic Data, FRED Graph Observations. Retrieved from https://fred.stlouisfed.org

- Dickinson, Maggie. (2019). The ripple effects of taking SNAP benefits from one person. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/family/archive/2019/12/trump-snap-food-stamp...

- Pavetti, Ladonna. (2018). TANF Studies Show Work Requirement Proposals for New Programs Would Harm Millions, Do Little To Increase Work. Center for Budget and Policy Priorities. Retrieved from https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/tanf-studies-show-wo...

- DeParle, Jason. (2020). As Hunger Swells, Food Stamps Become a Partisan Flashpoint. New York Times (New York). Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/06/us/politics/coronavirus-hunger-food-s...

- Blair-Lavallis, Yvette. (2019). Food is Political: how Food Apartheid is deeply impacting Black communities. Blavity News. Retrieved from https://blavity.com/food-is-political-how-food-apartheid-is-deeply-impac...

- Healthy Durham Diabetes and Food Access fact sheet. Retrieved from http://healthydurham.org/cms/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Obesity-Diabetes...

- Duke Health, and Partnership for Healthy Durham. (2017). 2017 Durham Community Health Assessment by the Durham County Health Department. Retrieved from http://healthydurham.org/cms/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/2017-CHA-FINAL-F...

- L’Tanya Gilchrist. (2019). Interview with Documenting Durham’s Health Histories Bass Connections Class, Duke University

- Audley, John, et al. (2004). NAFTA’s Promise and Reality: lessons from Mexico for the hemisphere. Retrieved from https://carnegieendowment.org/files/nafta1.pdf

- Pew Research Center Hispanic Trends. (2020). Hispanic Population Growth and Dispersion Across the United States, 1980-2014. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/states/state/nc/county/37063

- Nuevo Espíritu de Durham: New Spirit of Durham. 13 Sept. 2019 -5 Jan. 2020, the Museum of Durham History, Durham.

- Nuevo Espíritu de Durham: New Spirit of Durham. 13 Sept. 2019 -5 Jan. 2020, the Museum of Durham History, Durham.

- Nuevo Espíritu de Durham: New Spirit of Durham. 13 Sept. 2019 -5 Jan. 2020, the Museum of Durham History, Durham.

- Bread for the World. (2017). Hunger and Poverty in the Latino Community factsheet. Retrieved from https://www.bread.org/sites/default/files/hunger-poverty-latino-communit...

- Reichel, Chloe. (2018). After new immigration enforcement program, fewer Hispanic citizens enroll in SNAP. Journalist’s Resource, Harvard Kennedy Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics, and Public Policy. Retrieved from https://journalistsresource.org/studies/government/immigration/snap-aca-...

- Scott, Dylan. (2020). Study suggests Trump is scaring immigrant families off food stamps. Vox. Retrieved from https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2018/11/15/18094901/trump-immigr...

- Student Action With Farmworkers. Facts about North Carolina Farm Workers. Retrieved from https://saf-unite.org/content/facts-about-north-carolina-farmworkers

- Bracero History Archive. Retrieved from http://braceroarchive.org/history

“Most of us in this business are not enamored of Reagan’s plans in the least. We see that this effort to revitalize the economy is exploiting the poor to the advantage of the rich. There is no doubt about it.” – Sister Mary Wright, director of Urban Ministries (ref 275)

"When I was growing up, it [McDougald] was a community of pride. A stepping stone for the Black community. I didn’t know we were poor. We had three square meals, we had a warm bed, we had an indoor bathroom, I thought we were rich really. I didn’t know or understand there was a world outside of McDougald Terrace because we were just raised as a tribe. All the women there always banded together to make sure all of the children were protected...My oldest daughter was born in 88. That was a low time for the black communities when the drug addictions started coming in... and the drugs just started ripping apart the community. That’s when it actually became a project, to me." - Iris Arnette, on growing up, and then starting her own family in McDougald Terrace (ref 282)

“Being totally honest, high incarceration rates for people of color is very detrimental to our health. Even in the Durham County Jail, you have a canteen that's run through a private company, who only sells certain things like Oodles of Noodles- that are not healthy...And then in prisons, you don't get to eat vegetables unless its part of your dinner- and even then its often times still not healthy because of how it's cooked. But if you don't work in the kitchen, you don't get to decide- you just get it how it comes, and you pray over it and eat it.... But then over time, people get institutionalized in the system, and when they return home they continue to eat the same way, because they're used to it. And the financial piece only enhances that. Because you have individuals coming home, looking for employment, trying to do something different, and there are just so many barriers- even with food stamps. So it almost feels like you are being punished twice, and its very depressing. - Chuckwumeka Manning, activist and Director of the City of Durham’s Welcome Home program (ref 285)

“I’ve suffered a lot in this body… for a lot of people its genetic, but I feel like, and this is my personal feeling based on what I’ve experienced and my whole family, is the role of food deserts and the cost of food- not being able to have a community grocery store. And what I’ll say for Northeast Central Durham or the East Durham area where I grew up, we always had corner stores that sold everything that we didn’t need and very little of what we did need. Back when I was a child growing up, potato chips cost 16 cents a bag and you could get potato chips all day long and all night long, and people could get beer and wine in the neighborhood, but you couldn’t find fruits and vegetables until my daddy started selling it on the truck. So diseases come about sometimes genetically, but its increased or enhanced through living in poor poverty-stricken neighborhoods.” -- L’Tanya Gilchrist, Durham County Community Health Worker (ref 301)

“I remember a van would come, on Saturday mornings, and there were already people waiting in line to buy Hispanic products like fresh corn or flour tortillas because there were no tortillas at the grocery store” - Ana Santibanez (ref 304)

“At the beginning, we had a lot of needs. Where can I open an account, I need to learn how to use a debit card, I need to buy a car because I need to go to work, and then come the life changing decisions. In 2004, we started to see that folks were deciding to stay, to plant their roots.” - Vicky Garcia, Senior Vice President, Latino Credit Union (ref 305)

“For me staying connected with my culture has always been a priority: food, music, my people. I don’t agree that people have to forget their roots. This has allowed me to share with other people who I am, what is my culture, who are my people. It’s good to have a strong identity so you can share with other cultures and also assimilate into them. To share. And that’s how Durham identifies itself: in its diversity.” -- Ivan Almonte, community activist (ref 306)

“It’s our dream to come here, but in reality, it’s not a dream…Immigrants are being exploited every day. We have the power of working, we have the hands, but we do not have a political voice to call for our rights.” -- Katusha Olave, Bolivian immigrant to Durham and National Farm Worker Ministry community interpreter and literacy advocate (ref 313)